The late-capitalist revival of ‘community’ has transformed it from an organic social practice into a marketable idea of connection. Listening to the ‘men behind the counter’, this piece traces their histories, philosophies, and politics and what it takes to survive as an independent business in an ever-changing Edinburgh.

by Maria Farsoon and Meher Vepari

When asked about the lessons his mother taught him, one Edinburgh cafe owner responded, “Everything good. All the bad things, I learned alone.” It is often the perceived “bad things” to which the male immigrant in the UK is reduced, stereotyped, and criminalised. Simultaneously, it is often the male immigrant who focuses his energy on providing security to his family while he faces the threats of racism and injustice. Despite adversity, immigrant businesses operate with dedication. In a city like Edinburgh, it is this dedication that facilitates a strong community presence, without which, many individuals would feel isolated and endangered.

Mubashir, founder of Shawarma House, adds the finishing touches to the day’s dish. Photo by Meher Vepari

“9/11 was very hard for us,” Mubashir admitted. We spoke to him in the comfort of Shawarma House, his restaurant on Nicolson Street. At the time of the Twin Tower attacks, he worked in the Mosque Kitchen restaurant which served food to Mosque-goers after prayer sermons. Twenty-four years later, he recounts the experience clearly. “[To] go to work, go to mosque […] that time was tough,” he said. “A lot of people – there was hate in them. Because obviously the news only tells you – oh – 9/11 – terrorists – Muslims, you know? And brainwashes them. That’s it.”

“9/11 was very hard for us”

Scottish Muslims were no less ambushed than others. A young woman was spat on in Morningside, another smashed with a bottle in Glasgow. Windows of religious spaces were shattered in Portobello, Livingston, and Bathgate. A Mosque in Leith was firebombed at night and in Lanarkshire, 18 Muslim headstones were desecrated at a burial ground. In the Borders, posters encouraged onlookers to ‘Support the US and Attack an Arab Today’.

The Edinburgh Central Mosque also endured violence. Frankly and cautiously, Mubashir recalled vandalism, drunkenness, and smashed beer bottles. Police officers were stationed at the mosque’s three gates. “We’ve seen on TV – is that happening to us? You get worried,” he told us. Anyone who wanted to eat but “didn’t have money, we gave them. […] But they don’t see it that way. They see it the bad way.”

The tandoori oven at Shwarma House, hand-built by the staff. Photo by Meher Vepari

In direct response to rising racism, the mosque hosted an open day, “which really helped us”, Mubashir says. Outsiders learned “what the mosque and Islam are about”, he continued. Mubashir explained that following the sessions informing newcomers about Islamic values and teachings, “people [started to] understand Islam…lots of people converted to Islam”. This process was enabled through the distribution of free food. Generosity is a central practice in immigrant cultures and households; in the face of Islamophobia, the Mosque disarmed the city’s hostility through the unconditional sharing of food. During polarising, violent times, food invites newcomers and their solidarity, as BBurger themselves offered theirs during the May 2024 Old College encampment.

“We’ve seen on TV – is that happening to us? You get worried”

The founders emphasise transparency: “The people, they like a place like this…rich people love the place because they like the open kitchen, they see everything…fresh…very simple”, Nile Valley owner Abdul Abdallah says. The place offers the kind of comfort of a large family home. With an open kitchen and no uniforms, Abdul’s team of men keeps an essential pace. The busy queue peruses a dynamic array of posters as it waits. Downstairs, customers cover the distinct orange walls with images of friends and family; a place given to the local community by the owner himself, with trust and ease. Mubashir’s approach is similar: “Everything we do is in front of you. And you like it, Alhamdulillah. You don’t like it, tell us, we’ll do it that way.”

Nile Valley, Edinburgh. Photo by Meher Vepari

Established in 1996, Nile Valley also symbolises tradition in an otherwise rapidly-changing city. What started out as a dine-in restaurant, has now become a warm alcove inviting flurries of students and regulars alike, during the midday culinary rush hour. 12pm means human truckage, delivered in a determined frenzy of people who are, or will soon be, familiar with this constant of an establishment. There is no in between. Swiftly, Nile Valley switches between a place to eat and a space to catch a breath. From serving hot meals in the ‘90s, to sending customers out with their iconic hearty wraps, the ‘Nile Valley Look’ is immediately recognisable. On the walk of determination – or defeat – back to George Square’s Main Library, this sight is ubiquitous across students.

While Nile Valley is treasured amongst the university community, another joint responds most immediately to immigrants’ struggles. Shawarma House was officially established in 2019, humbly but surely taking the reins from various preceding unsuccessful businesses. Signing the lease on the same day of his daughter’s birth, owner Mubashir celebrated a new chapter in his compassion for others. As an 18th-century listed building, no changes or renovations can be made to the distinctive space under Scotland’s 1997 Planning Act. Shawarma House still features rubble masonry alongside the shop’s tandoori oven, handmade by the team themselves. Like the oven, the business’ ethos is sturdy and rooted. Mubashir acknowledges the “difficulty of delivery drivers’” lives, a demographic overrepresented by men and global majority individuals.

Abdul Abdallah, the founder of Nile Valley. Image by Meher Vepari

The economy of doorstep convenience is designed to obscure the struggles of those supplying it. Uber and Deliveroo drivers follow a silent agreement, inconveniencing themselves, risking their safety, and working unreasonable hours to the rhythm of hyper-consumerist society.

Speaking to Mubashir, we found an alcove where kindness collects and recuperates those often tossed to the side, left lonely and downtrodden, but unable to complain; for otherwise they would be ungrateful as well as unwelcome. For immigrants entering today’s Britain, demanding basic rights such as asylum, socio-economic security and the right to work translates to a display of ingratitude. Across outlets from Tommy Robinson to GB News, immigrants and asylum seekers – branded with the illegitimate term ‘illegal’ – are portrayed to ‘steal our jobs’ and contradictingly, ‘scrounge the system’. The reiteration by far-right actors that some immigrants are housed in re-commissioned ‘four star hotels’ with a meagre allowance, while the cost-of-living crisis encroaches on ‘British lives’, amplifies a dangerous paradigm in which basic rights for some are viewed as privileges for others.

Zak and Bilal at the counter of BBurger. Photo by Meher Vepari

In Mubashir’s candour, “it’s tough for them”. His not-so-secret menu spawned from a desire to cater for a community that – in its obligations to customers, employers, family members and the British state – often sacrifices providing for themselves. “My aim was to feed them,” Mubashir told us. “They don’t have money to go out and eat […] we tell them, don’t worry. Don’t be shy to come in […] this is your kitchen. You’re the boss – how’re we going to run this [without you]?” Mubashir’s animated and assured hospitality comes with sincerity: “They’re sad. They’re not happy here […] So speak to each other, get [it] out what you have in your heart.” Mubashir affirms his remarks with the familiar refrain: “this is a blessing from Allah, [alhamdulillah]”.

“They don’t have money to go out and eat […] we tell them, don’t worry. Don’t be shy to come in […] this is your kitchen. You’re the boss – how’re we going to run this [without you]?”

At 9pm, Shawarma House contains the city’s immigrant workmen who crave a home-cooked meal. Deliveroo boxes pile around the shop as the men enjoy their dinners, preparing for what is often the start of a long shift into the night. Drivers enjoy meals in solitude or in jovial company while community elders have counter-side chats in Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi and Pashtun. Sometimes, alarming news streams down from the corner; others, Bollywood darlings prance across the screen. Across faiths, nationalities and ethnicities, Mubashir’s customers are comforted by an irrevocable sense of home. “Pay one amount, but eat however much, until you’re full,” he told us; “I want you to be happy when you walk out.”

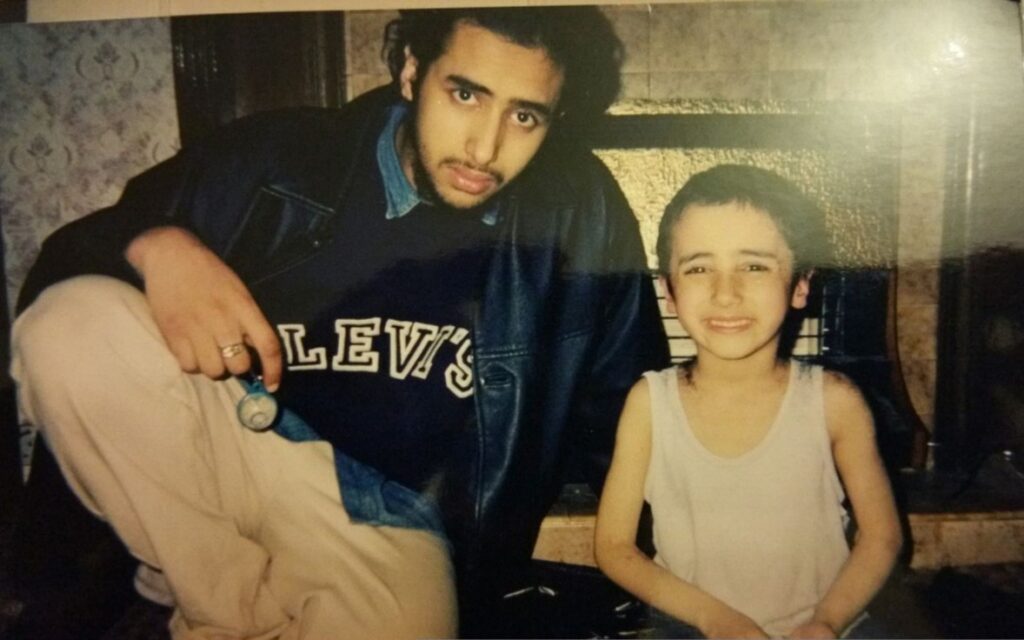

Zak and Bilal – the BBurger brothers – as young children in Scotland. Image provided by Zak

We feel as happy when we walk into BBurger, the first burger joint to open on Nicolson Street. Co-owners and brothers Zak and Bilal opened in August of 2017. They recall travelling to Glasgow “if we [wanted] to get a handmade burger back in the day”. Even during the Coronavirus Lockdown of 2020, BBurger “never closed one day, because we had a lot of – to be honest – we’d fallen into debt…and in the indirect way, it worked out well”. Ingeniously, the team decided to sell burgers to customers through a “hatch” in the window of the shop’s door, and made more sales than any other burger establishment in the city because of pressures to close down. All but BBurger, the product of two third-generation Pakistani brothers who recall growing up with the few other children of colour in Edinburgh’s Marchmont community “like [they] were all cousins”. The joint fosters familiarity when one enters. “It feels like going round to your cousins’ house, the stakes are so low, and it feels like you’ll always be cared for”, says a regular customer.

Mubashir, the founder of Shawarma House, prepares the 1-pot dish of the day. Photo by Meher Vepari

It became apparent in our conversations with the owners, if not already overt in their dedication to customer care and generosity, that they care deeply about the quality of the business. As independent businesses, all function with unique and individual character, marking their spot in the city as essentially irreplaceable. Another cafe owner we spoke to echoed this, describing his handpicked, thrifted decor as “economical”, and more sustainable than other enterprises which invest largely and consume conspicuously.

Zak and Bilal acknowledge the franchise opening of Chilo’s down the road from BBurger, but the conversation naturally flows elsewhere. The team is made of “[family]”, they say; “[our] nephew and auntie”. Recognisable faces are comforting, and ask us to slow down, not only when we eat, but when we speak to one another, and when we notice the society around us. Instead of following the capitalistic formation of community, reliant on the monetisation of social connection and the overconsumption, these places exist with intention. Multiple switched to alternatives when the need to boycott brands like Coca Cola grew within the city, within the past years. During times of mass panic, these are the places that are built with care, wherein the ostracised and the hungry alike, find refuge.

This article was produced as part of the Migrant Women Press Fellowship Programme 2025.

Maria Farsoon is a journalist, writer, and editor. She is interested in poetry, politics, and place. Her portfolio includes work for The Skinny Magazine and Plurality Journal. She is currently studying for an MSc in Publishing at Edinburgh Napier University.

Meher Vepari is a photographer and multimedia journalist. She is interested in social movements, the supply chain, labour and the stories of those who hold society together. Her portfolio includes work for British Vogue, Maktoob Media, and BreakThrough News.