As far-right hostility towards migrants grows across Scotland, local communities are responding by building networks of care, solidarity and resistance. From grassroots community spaces to organised anti-racist groups, everyday acts of connection are proving just as powerful as protests.

by Joanne Krus

As Scotland has seen the rise of the far-right hit closer to home, we have also seen the rise of communities coming together to show support for migrants. Charities, trade unions, community groups, local anti-racist activists and migrant groups have been working together to build a network stronger than the far-right.

The long road ahead looks steep, and protests will not be enough. Coming together over meals, youth groups, sports clubs, or craft sessions is proving to be an important part of strengthening our communities.

Milk was started in 2014 by co-founders Angela Ireland and Gaby Cluness as a cafe that served as a safe space for migrant women in Glasgow. Ireland explained: “We are primarily focused on refugee women and women in the asylum system, but all are welcome. You could’ve been here your whole life, or you could have been here 5 minutes, and you would be treated the same”.

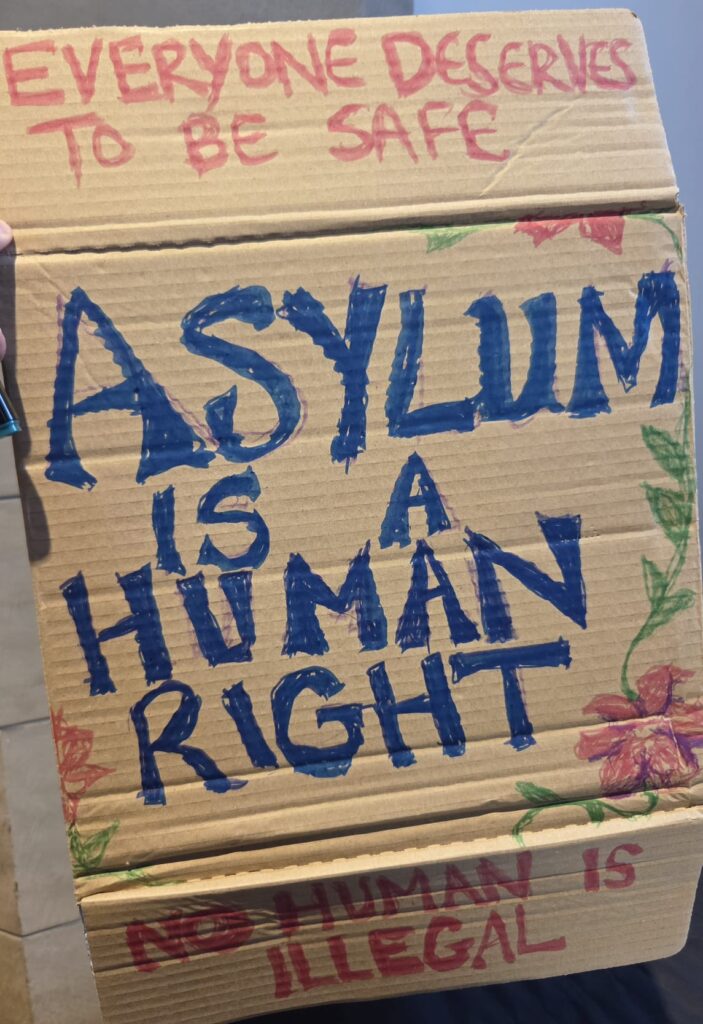

Milk placard welcoming refugees. Photo by Milk.

Their original goal was to teach migrant women transferable skills through their cafe: “We started Milk because we both loved working in hospitality. And we liked hospitality in the most traditional sense. You are welcoming someone into a nice space, feeding them and creating a warm environment.”

In the past year, they’ve moved locations and no longer work as a cafe, although they still run a catering business. Now they focus on workshops and advocacy work, running art classes, yoga, workshops and ESOL. Now they work to build a community space where people can come for tea, advice and get free food left over from the catering side of the organisation.

Milk’s community space was quiet when I visited, but it was clear that this was a rare calm day. All the hallmarks of a warm, busy community space are here. The walls are covered in children’s drawings and paintings, and there are toys and plenty of supplies for crafty workshops. It’s hard to understand how these kinds of spaces have become such targets for racists and xenophobes.

The entrance to Milk’s premises. Photo courtesy of Milk.

Ireland tells me that someone graffiti-ed “Feed us, not them” and what looked like a Christian cross on their shutters. They decided not to report this to the police, “I assume it was little boys” that did it, and that they don’t generally see much of a point in reporting these things.

They aren’t alone in these experiences. Any social media posts about a charity’s free meals or after-school clubs are met with “Why don’t you help us first?” These kinds of comments are littered all over charities’ and community spaces’ social media pages. Charities supporting women are constantly getting “what about the male loneliness epidemic?” and groups providing services in one postcode will be asked why they don’t help people in other areas.

“The anger is understandable, but the misdirection of it is inexcusable”, Angela

These comments point to migrants as a scapegoat for the reason that schools are struggling, local authorities are going broke, and no one can afford a house anymore. They ignore the decades of austerity and privatisation that have chipped away at public services and communities.

“The anger is understandable, but the misdirection of it is inexcusable”, says Angela.

Milk co-founders Angela Ireland and Gaby Cluness.Photo by Milk

How do we turn this anger into community building?

People are coming together to redirect this anger to more justified causes. I was interested to see how communities were organising to protect each other. This brought me to a Women Against The Far-Right organising event in Edinburgh. There are speakers representing groups across the country, including Perth Against Racism, Falkirk for All, Amina and Engender.

Cat Mackay, an organiser for Perth Against Racism, said that she started her journey on anti-racism campaigning nine years ago, when a racist group was set to march through town and walk past her house.

“I started as an angry mum.” She explained. Her daughter had a “diverse friend group”, and she couldn’t stand by while they were targeted. Since then, she’s been working in her community to make it a more inclusive and welcoming place. Her journey to activism really struck me. As a researcher, my work has often focused on getting people to care about migration through debunking myths and explaining the complex legal realities that shape migration and forced displacement. Mackay was a wonderful reminder that simply caring for your daughter and her friends can be a powerful motivator that creates a dedicated activist.

Communities are built by people caring for their neighbours, families and friends. However, it does feel increasingly difficult to build communities on care and empathy when far-right groups are intruding.

Pinar Aksu. Photo by Billy Knox

Pinar Aksu, a human rights advocate and Research Associate at the University of Glasgow, has also been doing this work for around a decade. She focuses on community development and using creative methods to engage with difficult conversations.

She is co-founder of Refugees for Justice, starting in 2020, after the Park Inn tragedy in Glasgow. Long before the far-right had anything to say about asylum hotels, charities and activists had been saying for years that the use of private for-profit hotels is unacceptable. The conditions are extremely poor for people seeking asylum, with mental health concerns going unaddressed, low food quality and forcing people into poverty.

Asylum hotels also prevent communities from coming together and having productive conversations. In turn, this helps the far-right stoke fear into communities by creating a boogieman, a dangerous unknown who is a threat to your way of life.

Aksu’s community development work aims to break this fantasy of the boogieman migrant by engaging in conversations. She got involved in Erskine in 2023, when far-right agitators exploited locals’ anxiety surrounding the announcement that a local hotel would be used to accommodate people seeking asylum. She asked people about what they were fearful of and what their communities actually needed.

Getting communities to ask themselves questions is key to weakening far-right beliefs. By shifting the focus from migration to more systemic issues, you can build stronger bridges.

Pinar Aksu

“When I was at a protest in Falkirk, where I spoke to a group of teenagers, and I asked them: ‘Let’s say the hotel in Falkirk is closed. Do you think all the problems in your community would be solved? Is that an end to poverty? Is that an end to all the violence against women? Is everything going to be great?’ And it was interesting, you know, they were thinking, no, the problems are still going to be here. So then you get that realisation of ‘Right, do you see how it has nothing to do with anyone who’s placed in hotels?”

“I think it’s going to be a long process where everybody needs to work together to sustain it.” Pinar

Aksu says that these are the basic building blocks to strengthening communities. If you can have difficult conversations and identify structural issues, then you can work together to fix these issues. Like the organisers of the Women Against the Far Right, she seems optimistic about the community organising that’s happening across the country: “I think people are starting to organise, and they’re organising by working together.”

“People are feeling more confident, which is amazing. But it’s taking quite a long time, and I think it’s going to be a long process where everybody needs to work together to sustain it.”

Photo by Pinar Aksu

This is why spaces like Milk are so important. Community spaces built on care might not make national headlines, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t making an impact. This everyday work happens behind the scenes to produce a sustainable network of strong communities ready to show up for each other.

It’s this network that made the events of Kenmure Street successful. That day, people came together to show up for our communities and our values. We knew nothing about the two men taken in by the Home Office; we just knew that it was wrong and they needed the community’s help.

We believed in welcoming refugees, and we believed that hostile policies shouldn’t rip apart our communities. The power of that moment has stayed with me, and Glasgow continues to discuss it with pride. These networks haven’t gone away, and they continue to build across the country. The headlines might depict a country divided on migration, but when you go to your local community spaces, you find that that is far from the truth.

This article was produced as part of the Migrant Women Press Fellowship Programme 2025.

Joanne Krus is a journalist and researcher. She works independently and with NGOs to tell stories that amplify migrants’ voices, show the reality of hostile borders and hold authorities accountable. Her work focuses on migration, border violence and border policing technologies.