One year after the DANA storm devastated the Valencian Community, in Spain, migrant women continue to face the invisible consequences of racism, bureaucratic neglect, and institutional silence.

by María Plata, Marina Moreno & Nieves Pallarés

“The DANA storm uncovered the curtain on the racist and colonial state that leaves people behind, especially migrants.” This is how Silvana Cabrera, spokesperson for the Regularización Ya movement, expressed her frustration with the Generalitat Valenciana government’s response to the DANA storm on 29 October 2024.

The measures added to the Immigration Law to regularise migrants — which aimed to regularise 25,000 people — reflected the structural and colonial racism that still persists in Spain, particularly against migrant women.

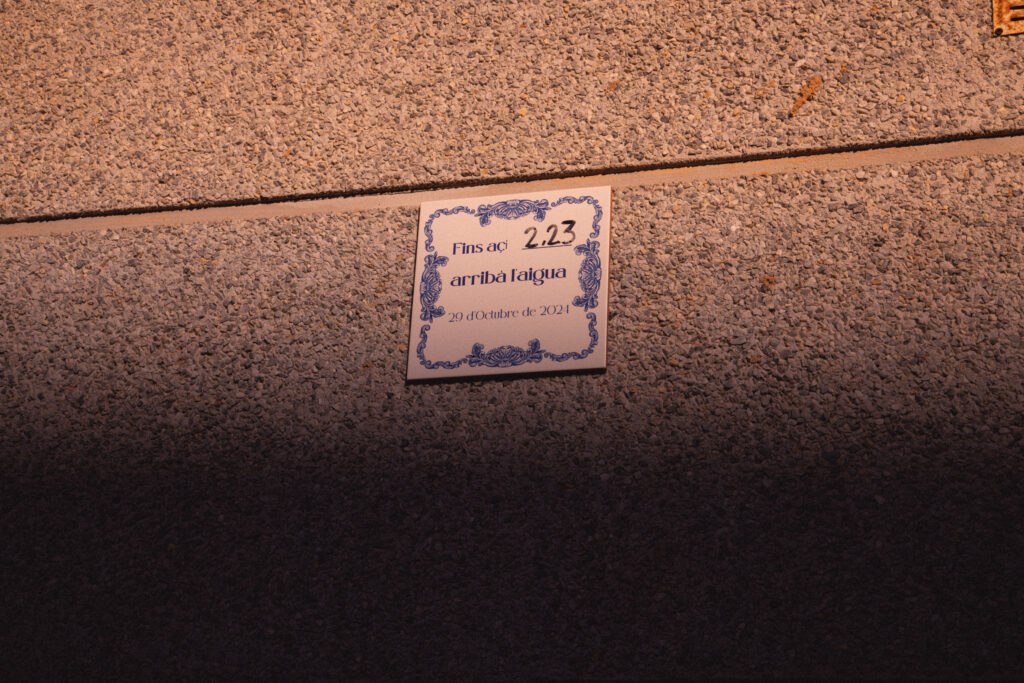

On 24 October 2025, everything was calm, quiet. It was warm. A man walks along the cycle path by the river. House. Nothing. House. There is no mud now, but DANA is here. It walks. It is present. On the terraces, in the parks and on the balconies of the houses.

On 29 October 2024, at 8:11 p.m., the phones were ringing. However, the overflowing Magro River had already left most of the deaths from this catastrophe in its wake. A month later, while aid, mostly from the third sector, was assisting those affected by the tragedy, María (fictitious name) was fired amid shouts.

María lived in the ground floor flat of the person she cared for. When the water began to flood the house, the neighbour upstairs had to let them in. Without any documentation proving that she lived and worked in one of the areas affected by the DANA, María was left homeless, unemployed, and without any access to assistance.

“Domestic workers are mostly migrant women in an irregular situation,” explains Dolores Jacinto Nieto, coordinator of the Intercultural Association of Home and Care Professionals (AIPHYC). The underground economy represents between 17% and 20% of GDP in Spain, and it is mainly migrants who sustain it. As they do not have the administrative status that would allow them to access an employment contract, they are forced to accept precarious, undervalued jobs that violate human rights.

The new measures proposed, which aimed to regularise the status of 25,000 people, required proof of residence in one of the affected areas between 28 October and 4November 2024. This requirement excluded those who, like María, could not prove their address because they were not registered due to multiple administrative barriers.

A clear example is that of migrant women working as live-in carers.

“There are many rights violations that occur in the overnight accommodation system, especially with regard to privacy, health and freedom of movement”, Dolores reports. They are used as disposable objects.

Mental health has been largely overlooked among the consequences experienced by these women after the DANA. Many suffered institutional violence when they were denied any help from the public authorities. Dolores recalls that several users reported having suffered abuse when they went to Social Services, where, as soon as they saw the physical characteristics of the women, they received an impassive response. “I went to Social Services, and as soon as the worker saw me, she said: ‘If you’ve come to ask for help, we don’t have any here'”, says María.

This form of colonial extractivism that migrant women have to face confronts them with a reality that considers the act of feeling as a privilege rather than a right. When you find yourself without a contract, without unemployment benefits, crammed into tiny rooms with your children and with the responsibility of sending money to your family, you cannot afford to feel.

“Migrant women are in a constant state of survival, and mental health is the last thing on their minds when something like this happens”, says Dolores.

The number of administrative obstacles following the DANA has led to an increase in mental health problems that are still evident a year later.

“Now is when we are starting to see many episodes of anxiety”, says Silvia Iglesias, psychologist at Por Ti Mujer Association.

Unfortunately, this is not a new phenomenon. We saw the same situation during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the facilities -of any kind- provided to the population did not consider cultural diversity and, especially, linguistic diversity. This exacerbated the number of cases of anxiety and depression that are now being seen.

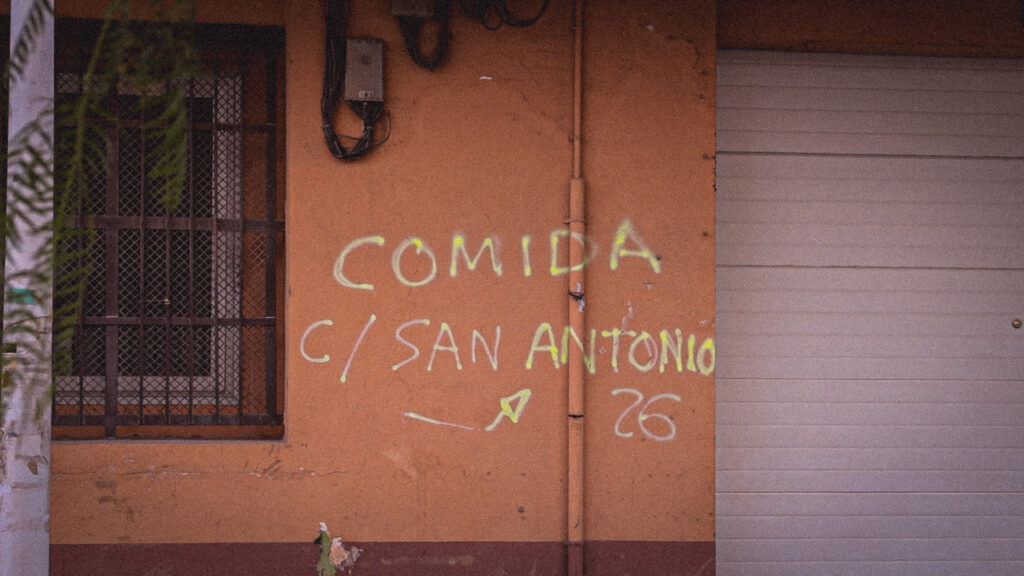

The social isolation caused by a lack of intersectionality in public administrations has led to an overload on the third sector, which is demanding an urgent change to meet everyone’s needs. “If anything can be highlighted during the days and months following the DANA, it was the associative movement,” Silvia points out. This was what sustained a population that was

marginalised by the administrations, providing them with adapted health resources ,information, or any other type of assistance.

It was social organisations that travelled around the areas of Alfafar, Benetúser, Massanassa, Catarroja, Paiporta and Picanya, providing adapted information and direct assistance. “Casa Marruecos was concerned about the whole issue of halal food, which was something that was not even taken into account”, recalls Silvana Cabrera.

This work highlights the lack of consideration and willingness of a government that ignores the diversity of its citizens. As Silvia points out, “these women need adapted emergency aid, just like their neighbours who are in a regular situation.”

The DANA storm on 29 October 2024 was a stark example of this, where the structural shortcomings of the state and public management arise with violence, and the most vulnerable groups bore the brunt of the impact.

The Immigration Law affects the daily lives, access to work, education, healthcare and welfare of hundreds of thousands of people in Spain. However, as long as regional and national governments fail to accept that migration is an inherent part of the human condition and fail to recognise the diversity of its society and its different needs, it will be impossible to implement truly effective solutions.

Only through the active participation of migrants in the decisions that affect them will it be possible to develop fairer, inclusive and sustainable policies.

This article was originally published on Substack

Marina Moreno is a content creator from Quart de Poblet, Valencia. She studied Audiovisual Communication and currently works as a video editor at an advertising agency while also pursuing personal projects and creating content for other brands.

María Plata is from Cádiz, Andalucía. She studied Criminology and Social Intervention. She works as a social educator with teenagers and other groups at risk of social exclusión.

Nieves Pallarés works as a freelance journalist. She’s from Castellón, Valencian Community. Her career is based on communication in the third sector, dealing with topics such as migration and human rights.