We introduce our first columnist – Sabrina Galella, whose debut piece sets the tone for a powerful new column on women’s rights. At a moment when spaces for resistance feel smaller and the world more uncertain, this column offers an invitation to reflect, connect, and stand together.

Written by Sabrina Galella

This column is not about me, but I thought it would be good to say a few things about myself and the idea behind this space.

I am Sabrina – a migrant woman from Italy who has made Edinburgh her home for the past decade. I have written for Migrant Women Press before, and my topics have always revolved around social justice issues with an intersectional feminist lens.

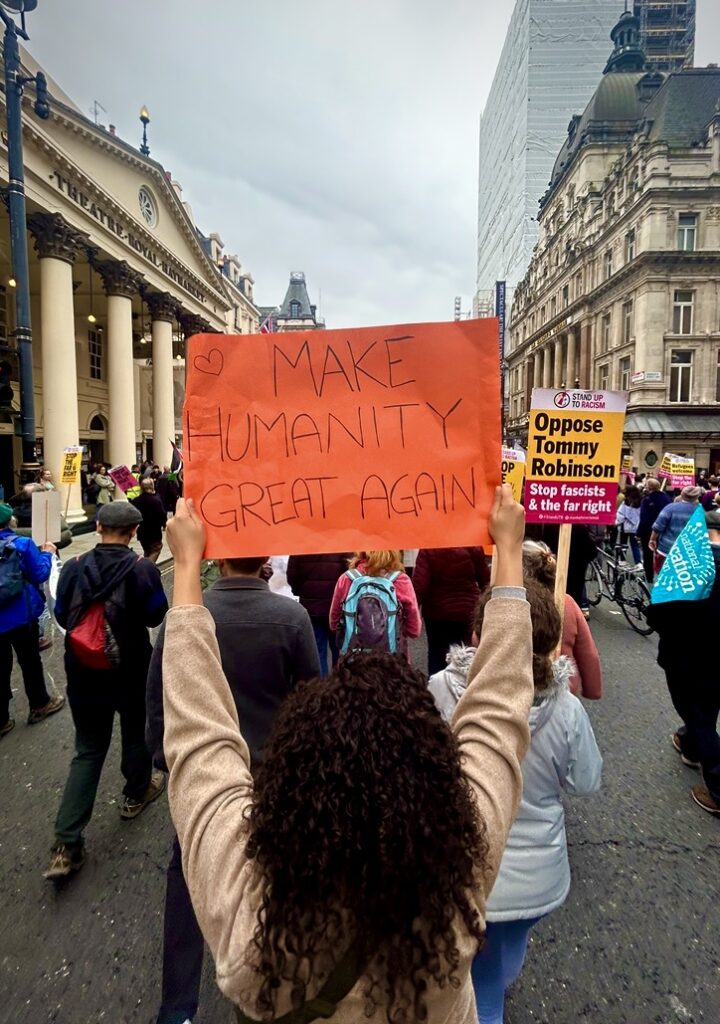

And I am afraid this column will not be much different, but I hope we can create a space where we collectively add to the conversation about feminism – adding voices, adding depth, adding change. I hope we can make it easier to discuss gender oppression in relation to other systems of oppression – cutting through the noise that aims to divide us to find shared support and resistance.

I think one of the reasons I wanted to write this introduction was to set the scene as to why it’s important to talk about social justice, and what that looks like for women – all women – here in the UK and across the world.

I learnt feminism from my mum, as she has felt the boot of patriarchy on her neck her whole life. And so, over the years, I organically interpreted the world in a way that framed social justice issues as feminist issues – but lately, that has felt like a much more contested activity, a lonelier space, an angry one. Many of the things I take for granted and around which I have built some of my core values often don’t make sense to other people or are perceived as naïve and idealist.

I am not going to lie; I have thought countless times that it was because of their ignorance – when it is my own arrogance I should look at. That arrogance has warped conversations and left a crack that continues to widen because of the simplistic habit of dividing the world into those who care and are inherently good and virtuous and those who don’t and are just ignorant and not worthy of time.

The truth is that we are doing the social justice movement a massive disservice every time we walk away from a difficult conversation, every time we choose arrogance over curiosity, and every time we think it is more important to win the argument than to learn new perspectives. So far, for me, it has created a society that I don’t often understand but by which I am not understood either.

As a matter of fact, I am not inherently better or worse than any other person. Of course, I try to be a decent human being, but that’s also the combination of favourable conditions. In other words, I sit on privilege – the privilege of being white and European, of enjoying freedom of movement without the burden of permits and visas, of being in a heterosexual relationship, of not knowing first-hand war, violence, food insecurity or private healthcare.

And if that’s not enough, the privilege of having parents that gave me enough space and trust to explore life for myself, knowing that if things ever got tough, I could wave a white flag and rely on them. I had a favoured start, and while it didn’t take away from my personal challenges, I could still rely on a system built to work for people like me.

Would I have been so involved in this fight if I hadn’t been dealt a good hand? I really like to believe so, but it would be arrogant to think it wouldn’t cost more unpopularity, confrontation, and danger. And because mine is not a story of survival, I had time and means to investigate humanity’s struggle for justice and make it my life’s dedication too, and that had led me here – aware of the indisputable fact that injustice is gendered and so is violence, war, poverty. The irony of writing “indisputable” is not lost on me, while 50% of British young men believe that feminism has gone too far and makes it harder for them to succeed.

In all honesty, that’s one of the many traps I find scattered throughout these conversations – the idea that to make space for some people, something else must be taken away from others. That feminism is a zero-sum game seeking to reverse power dynamics. That’s a misconception, and the goal is not to win – the goal is to survive first, then to be safe, then to choose over our own bodies and careers and goals, then to have access to equal opportunities, and then to thrive. To exist in our own right.

To me, feminism – one that is intersectional and sees the different systems of oppression as a catalyst for resistance and empowerment – doesn’t leave anyone behind. And yet, for many, it has gone too far. And my question is – how do we, as a collective, create a meaningful space for factual conversations to take root?

Do we even want to have those conversations, or is this, as Audre Lorde put it, “an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns”?

I am conflicted, but for a long time, I thought we could rely on facts to speak the truth. The facts tell us that around 650 million girls across the globe are married before the age of 18.

Over 230 million women and girls have undergone female genital mutilation. 71% of all modern slavery and human trafficking involve women and girls, with migrant women at an increased risk.

753 million women live in countries with restrictive abortion legislation – over 39,000 women die every year as a result of unsafe abortions. Black women and women from low-income countries or communities often suffer the most.

In low and middle-income countries, women represent 75% of people with disabilities – facing increased discrimination and sexual abuse on account of both their gender and disability.

500 million women and girls lack access to basic menstrual products and sanitary facilities – managing periods during a genocide has become impossible for women in Gaza.

In many countries, women can’t vote, drive, get a divorce, study, or work.

But I have been told that those general numbers don’t paint a picture to which people can relate because they somewhat feel distant and that it is important to explain how things are unequal closer to home. I disagree with the idea that we need to “relate” to care, that unless we see something of ourselves in others, we can’t empathise with their sufferings. Why can’t our shared humanity be the measuring stick?

In a conversation, this is where I would start to feel uncomfortable, and I’d begin to think there’s a better use of my time than to convince a misogynist prick that women’s rights are human rights. But I am committed to creating more constructive conversations, so here goes.

In the UK, every three days a woman is killed by a man. Their stories are often just background noise.

One in four women will experience domestic abuse, and one in five will be the victim of sexual assault during their lifetime.

Fewer than 3 in 100 rapes recorded by police resulted in someone being charged that same year – let alone convicted.

Migrant women are more vulnerable to violence, but the ‘hostile environment’ makes it more difficult for them to access support, advocacy, and criminal justice measures.

Women have less access to well-paid and secure work and are more reliant on inadequate and shrinking social security entitlements – even more after the cuts to disability benefits.

Women also make up the majority of single parents, primary caregivers for children, and unpaid carers for disabled and older people.

Those inequalities are compounded by other forms of discrimination and are experienced more acutely by disabled women, Black and Minority Ethnic women, LGBTI women, women with insecure immigration status, low-income women, women in minority faith groups and unpaid carers all across the country.

We all know one of these women because we are these women.

That is just the tip of the iceberg, and that’s why I believe it is essential to keep talking about these issues – because we are not free until we are all free.

This column won’t be about me, but I hope we can use this space to build a small community to have those conversations because with community comes empowerment and from empowerment comes liberation – and that’s half of the solution already.

I don’t know how to do that on my own, but I would be happy to have a chat about how we talk about women’s rights and bring more people along this journey in a space that continues to shrink.

Sabrina Galella is an Italian migrant and a human rights practitioner. After her degree in Politics and International Relations in London, she earned an LLM in Human Rights Law from the University of Edinburgh. She is the Senior Policy Adviser to Devolved Nations at UNICEF UK and a volunteer for the Gaza Families Reunited Campaign.

Get in touch with Sabrina via email – sabrinagalella@gmail.com – or find her on LinkedIn.