As a woman who has experienced the journey of menstruation, I have had the great privilege of always being surrounded by exceptional women, studying with illustrious feminist writers, and working with great colleagues dedicated to the global fight for the rights of women and girls. I now find myself reflecting on my own experiences, which began when I was nine years old and continue as I approach menopause as my daughters embark on their paths to menarche.

✍🏾Sandra Ruiz Moriana 📷 Echo_Visuel (Instagram)

My first period began when I was nine years old, and I remember it with anger – my mother called all my aunts to tell them the great news: I was now a woman!

Although this public celebration I know that it was done with all the enthusiasm and affection of a mother, it made me feel ashamed and displeased (similar ritual to the “Ritushuddhi”, a Hindu ceremony celebrating the start of menstruation). Brick compresses, insecurities, and discomfort followed this! I practised Taekwondo daily, and the “Dobok”, the uniform of this sporting discipline, is entirely white. Can you imagine?

Going to the beach with your friends and keeping the string of your tampon hidden from view was quite a challenge, or discreetly asking your friends to check for stains after a class session – it was the norm! I don’t recall a single session on menstrual health education in school. My friends and peers were my best educators!

In 2008, I travelled to the Saharawi refugee camps. I remember that one night, in the moonlight, I washed naked with buckets of water in a small mud room while some local girls illuminated me with flashlights. While I was taking a shower, they stared at me while I tried to explain to them that I had my period and I was not about to die because I was cleaning myself (they were prohibited from bathing or praying during their period following the rules of their religion). And although I remember they looked at me with curiosity and amazement, their answers were crystal clear – you are different from us!

After I lived in Ireland for 12 years, where, as an adult, pharmacies sold me menstrual products with great discretion, if I needed someone to lend me a tampon, it seemed more like an act of drug trafficking than a simple donation, and if you talked about it with Irish friends, it had to be in a low and cautious voice, so that no one overheard the conversation. I always attributed it to its deep-rooted connection to the Catholic religion, although Ireland is a very progressive country with great feminists.

Three years ago, my daughters started at a school in Barcelona, and with them, I began my immersion in Catalan education as a family representative on the school council. Because of my passion and professional training, I always put on my purple glasses and look at the whole from the perspective of diversity and equality.

It was then that I was surprised by patterns of behaviour and beliefs that showed a lack of information in the area and little progress in it. For example, I was surprised by some families’ belief that taboos or prejudice related to Menstrual Health were something of the past, and in Catalonia, that problem no longer existed. Also, the primary schools lack the infrastructure and resources to guarantee dignified and safe menstruation.

For this reason, I decided to conduct a survey on the current situation of menstrual health management in primary schools in Catalonia, but I ended up doing more in-depth research on the topic.

During the preliminary investigation, it became clear to me that there are numerous articles, entities, and professionals who have been working for years to advance this topic at a national and international level, although the first official investigation about menstrual health and education in Spain carried out by a team from the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and the Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV), was only published in 2023 [1]. This research analyzes how menstruation is treated from an early age and confirms that education on menstrual health in Spain still needs to be improved.

A bit of background

The menstrual cycle, which directly impacts 50% of the world’s population, is simply another natural physiological process of the human body. Although it is usually related exclusively to women and girls due to vaginal bleeding, not all women menstruate. Men also have a monthly hormonal cycle and andropause [2] (although there are still few studies in this field).

Since prehistoric times, menstruation has been referred to in a generally negative but multidimensional way. Superstitions, fears and social taboos have been enshrined since primitive times and have been transmitted through societies, religions and education, always subject to a patriarchal discourse. These societal attitudes profoundly impact women’s experiences and highlight the urgent need for societal change.

“For the Persians (800 B.C.), the woman who had had a child, like the woman who was menstruating, was “impure” and was isolated for four or more days in a room with dry straw scattered about fifteen steps away from fire and water, the clean elements [3].”

In the Jewish Talmud, Koran (Quran 2:222) or Bible (Leviticus 15, Bible), sacred and Millennial books, passages appear around the female period in which they force men to stay away from their wives during those impure days. Menstruating women must follow explicit rules, such as not sleeping with their husbands during those days, not bathing or praying, or having sexual acts – among many other mandates.

The common denominator is that women are the ones rejected and penalised for menstruating instead of raising recognition and empowerment for this vital physiological process, which is so crucial for humanity. It has sometimes been different in some historical cultures, such as the Cherokee [4] (USA), where menstruating women were considered sacred and powerful.

Obviously, these beliefs were not built alone. Language has always played a fundamental role in shaping people’s thoughts and, consequently, their actions.

Kohen and Meinardi (2016), in their article, confirm that “in colloquial language, we find numerous terms that help talk about “that which is not named” (menstruation) [5]. The language we use influences those myths, taboos and negative associations about menstruation. In 2020, the menstrual health application Clue collected twenty euphemisms in Spanish about menstruation in a global survey supervised by the International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC) [6].

As part of my personal research, I have compiled some euphemisms from different parts of the world, including Ireland – some quite humorous and original. However, all of them are thought-provoking (thanks to all the women who have helped me with this compilation):

- Red traffic light

- The monstruation

- The red one!

- The monthly visit / It’s that time

- My friend, the communist

- The tomato

- Little moon “Lunita”

- The Pepa

- I’m with Inés, the one who comes every month.

- On the rag

- My flowers

- On the blob

- The painters are in

- The Japs have landed (They refer to the Kamikaze pilots of World War II).

Along with euphemisms, myths have also been passed down from generation to generation, with many still in force today, and popularly accepted as the mayonnaise myth – “If you make mayonnaise while you are on your period, it will be off!”.

According to Iglesias Benavides (2009), they explain that “Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) in Rome, in his Natural History, where he says about menstrual blood: “But nothing can be easily found that is more notable than the monthly luxury.” Women’s. Contact with it turns new wine sour, crops touched by it become barren, grafts die, garden seeds dry up, fruit falls from trees…”[7].

Fortunately, language is evolving, and more inclusive and innovative language is currently used to avoid perpetuating myths related to menstruation. But there is still a lot of work to be done, and education always plays a vital role in this.

Global menstrual activism

Although a current of menstrual activism began in the 1960s and 1970s, it was not until the fourth feminist wave (approximately 2017) that a branch of feminist activism emerged globally and more forcefully from a more intersectional and multidimensional vision. Under the name “menstrual activism,” it strives, among other things, to effectively manage menstrual health and hygiene (SMH).

In 2014, a report published by UNESCO [8] estimated that 1 in 10 girls in sub-Saharan Africa do not attend school during their menstrual period. It has been suggested that this could equate to approximately 20% of a school year. These results reveal the significant impact on girls’ education and the negative consequences that these absences have for their futures.

In 2016, the term “period poverty” was coined. According to Pascual Armedáriz (2021) [9] in his study, “Menstrual poverty is not only related to a person’s economic capacity…four components of menstrual poverty are interrelated: Lack of access to menstrual products, lack of access to bathrooms and sinks, the treatment of disposable products and the lack of access to menstrual education.

It was only in 2023 when the United Nations, in its 53rd General Assembly on Human Rights [10], addressed the issue of Menstrual Health and declared that Menstrual Health is an issue of human rights, not just health, and all People have the right to bodily autonomy. They also highlight the importance of Menstrual Hygiene Day, celebrated annually on 28 May, as an opportunity for States to commit to the adoption of awareness-raising measures and to address stigma related to menstruation.

Several global projects have strong voices advocating for Menstrual Health for all women and girls, for example, the “Heshima Ya Binti (Dignity of a Girl) project” in Kenya. “For approximately seven years, Children’s Rights Trust (PCRT) [11] has been implementing the “Dignity of a Girl” project, providing reusable pads to secondary school girls in Tanzania’s rural and peripheral urban areas. As a result, this project has reduced school absenteeism and increased girls’ confidence. It also works to raise awareness among girls, families, and the community in general about personal hygiene, the menstruation process, and taboos. “Girls are now aware that pads are a basic necessity!” – says @Angela Infuya (Founder).

In addition, the Government of Kenya led to a policy eliminating VAT on imported menstrual products in 2004 and raw materials for their production in 2016. Similarly, Nigeria eliminated VAT on locally manufactured products. Countries such as Malaysia, Lebanon, Tanzania, Ireland, Colombia, and Mexico have all eliminated VAT on period products [12].

There have also been developments elsewhere. In 2015, menstrual health campaigns in the U.K., “the Homeless Period”, called for the free distribution of menstrual products. Likewise, in the USA (2016), New York became the first city to distribute free tampons and pads in public primary schools and other public centres.

In Europe, starting in 2022, the E.U. will allow Member States to sell menstrual products without VAT. For now, Ireland is the only one that does it. Most have reduced taxes by 5 to 10%. The Scottish Government passed a law in 2020 to ensure the distribution of free menstrual products through schools, colleges and universities.

In the particular case of Catalonia, a pioneering campaign was launched in 2023, “My period my rules”, within the Menstrual Equity Plan [13], which offered two free reusable menstruation products to all women and girls of menstruation age. The distribution of these reusable products also aims to reduce waste and have a positive environmental impact. According to the regional Government, Catalonia alone generates a footprint of around 9,000 tons of waste from single-use menstrual hygiene products for the planet.

Intersectionality and menstruation

Before returning to Catalonia and analyzing the survey, I would like to highlight the importance of understanding that menstruation does not affect all women similarly and that the impact is related to intersectional factors. Intersectionality is a concept that sheds light on how multiple dimensions and systems of inequality interact with one another and shape an individual’s experiences and opportunities.

This means that when we examine menstruation and menstrual health from an intersectional viewpoint, we need to discuss this in the context of women with disabilities, migrant and refugee women, women from minority ethnic backgrounds, etc.

From my perspective, I am particularly interested in menstruation and how it affects young migrant women in transit or living in shelters. These young women are often in a situation of helplessness and risk, immensely vulnerable during their migratory journey. The lack of information and education, taboos and prejudices, lack of adequate infrastructure or menstrual products, challenges during transit, and cultural and religious beliefs can make the experience a great challenge for them, and expose them to serious health risks. More investment is needed in this area to conduct analysis and consequently develop urgent measures to address these issues that affect many migrant girls and women in different parts of the world.

There are only a few academic articles that show this reality; Soerio, Rocha and Surita (2021) [14] researched menstrual health and young migrant women from Venezuela on the borders of Brazil. They report the following:

“Young women (aged 10 to 24) are typically a neglected group in humanitarian settings (situations of forced displacement, armed conflict, or natural disaster) and, in these contexts, they barely have access to menstrual hygiene products, safe toilets, or water. …We found that almost half of menstruating participants (46.4%) did not receive any hygiene kits, 61% could not wash their hands when they wanted to, and the majority (75.9%) did not feel safe using the kits. Bathrooms, which shows the poverty of the period (lack of menstrual supplies, private bathrooms, sanitary conditions and education) that affects the well-being of these women, especially during humanitarian crises.”

Making visible the intersectional nature of menstruation makes it possible to understand the different needs and reduce the social, physical, and psychological impact of menstruation on women in any space. It makes it possible to understand the different profiles and their individual needs. And this intersectionality and diversity must be taken into account in all schools when addressing this issue.

Primary Schools and Menstrual Health in Catalonia: Survey Results

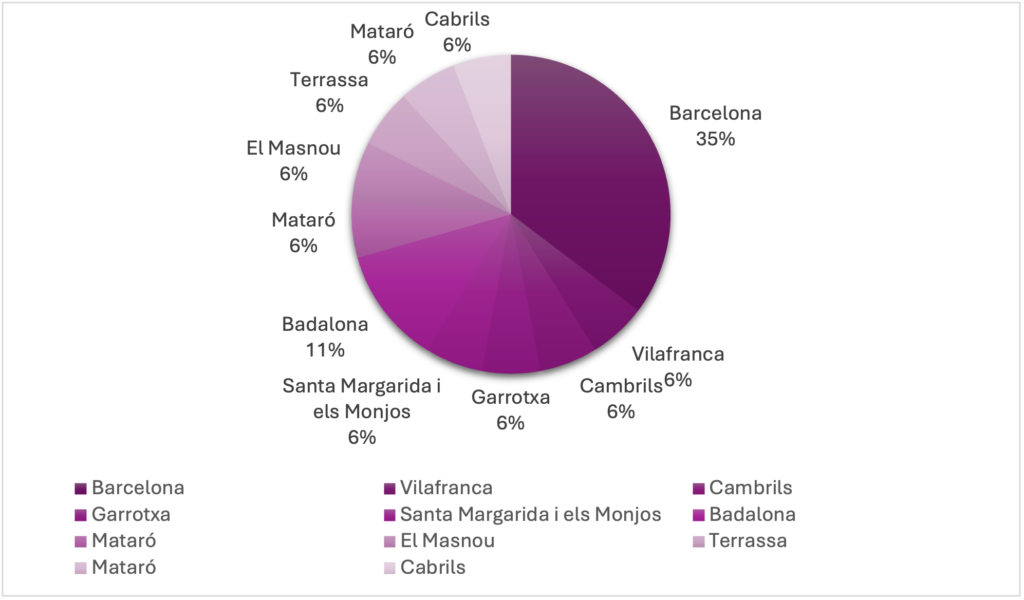

This brief and informal survey in Catalan was carried out during the summer of 2024. Although the number of participants was not significant, it is revealing. Seventeen professionals from public primary schools located in different parts of Catalonia, mainly from class B (the socioeconomic category of the school defined according to the socioeconomic and cultural origins of the parents), responded to the survey. The profile of the respondents mainly comes from the teaching team (13), but also from the management team and others, such as free time monitors. The average number of years working is six years (the maximum being 15 and the minimum being 1).

While the survey is informal and localized, it serves as a crucial call to action, underlining the necessity for more comprehensive studies with a multidimensional and intersectional perspective. This need is not just a suggestion but a vital step towards understanding and addressing the challenges faced by the educational community. The survey brings to light the need for more information and support for the education community and the urgent requirement for specific and viable policies to ensure compliance with this fundamental right. It also underscores the need to invest in the renewal of school infrastructure, creating adequate and safe spaces and bathrooms that allow girls to manage their menstruation with dignity.

“The toilets for the middle and upper cycle students are not prepared, they do not even have toilet paper. Paper must be taken in the classroom, and the bins are office bins, not suitable for menstrual products. There are only 3 toilets spread out (1 per floor) accessible to teachers throughout the school and to families, these are the only ones that have bins suitable for menstrual products.”

The survey results are fully shared in the Spanish version of this article.

Some recommendations:

U.N. Women and other organisations have published different measures to advance the menstrual health of women and girls. These are some of them, especially recommended for girls of primary school age:

- 1. Reconstruct the narratives related to menstruation and disseminate more real, balanced, and fair information while remembering the multidimensional and intersectional nature essential of women and girls’ experiences. Kohen and Meinardi (2016) pointed out, “Not the entire population has access to this knowledge; for that reason, the school plays a fundamental role since it has the potential to democratise knowledge” [15].

- 2. Promote awareness, eradicate myths and taboos, ending the stigma around menstruation. Such awareness raising should be mandatory in primary schools for boys and girls, at least from the 3rd and 4th grades. “Integrated education for all people would help put an end to gender inequalities since it normalizes the menstrual cycle and stops it being a ‘women’s thing'” (Pascual, 2021), [16]

- 3. Learning to manage menstruation with dignity and safety as a public health and human rights issue.

- 4. Sustainable distribution of menstrual products. Designing a multidimensional educational plan drawn up for the entire educational community from the first cycle of primary school.

- 5. Provide menstrual products with optimal awareness-raising infrastructure to guarantee security and privacy. Considering that some girls begin to menstruate from the age of 9, we need primary school bathrooms to be equipped for all menstrual products, including organic ones. We need clean, safe bathrooms without unnecessary gaps above or below the door, with cubicles, access to soap and water, toilet paper, and specific bins for disposable products—basic requirements to avoid diseases or infections such as toxic shock.

- 6. Stop the systematic economic/taxation practices that harm the well-being of women. Anna Freixas, the Spanish author of one of the pioneering works in feminist gerontology, calls not to forget the attempt to “business that is systematically done with the lives of women.” [17]. Ensuring the elimination of taxes on monthly products and guaranteeing them accessible to all girls and women should be unavoidable.

- 7. More investment in data collection- Research from an intersectional perspective. The English author Caroline Criado Perez, who wrote the bestseller “The Invisible Woman” [18], speaks clearly about this in her book. It is clear that by omitting data segregation by gender, we are promoting the invisibility of 50% of the world’s population. We need more investment in menstrual health research. The toilets for the middle and upper cycle students are unprepared; they do not even have toilet paper. Paper must be taken in the classroom, and the bins are office bins, not suitable for menstrual products. There are only three toilets spread out (1 per floor) accessible to teachers throughout the school and to families; these are the only ones that have bins suitable for menstrual products.

It is essential to understand that menstrual health is not just a matter for women and girls – it is a human right – and we are all responsible for guaranteeing it. Furthermore, it affects all women anywhere in the world, and taboos and prejudice continue to exist in all societies, including those located in the so-called developed countries or the northern hemisphere,as is the case of Spain. From East to West, from North to South, we continue to suffer stigma, social rejection, and risks to our health, in addition to being penalized for the simple fact of being a woman.

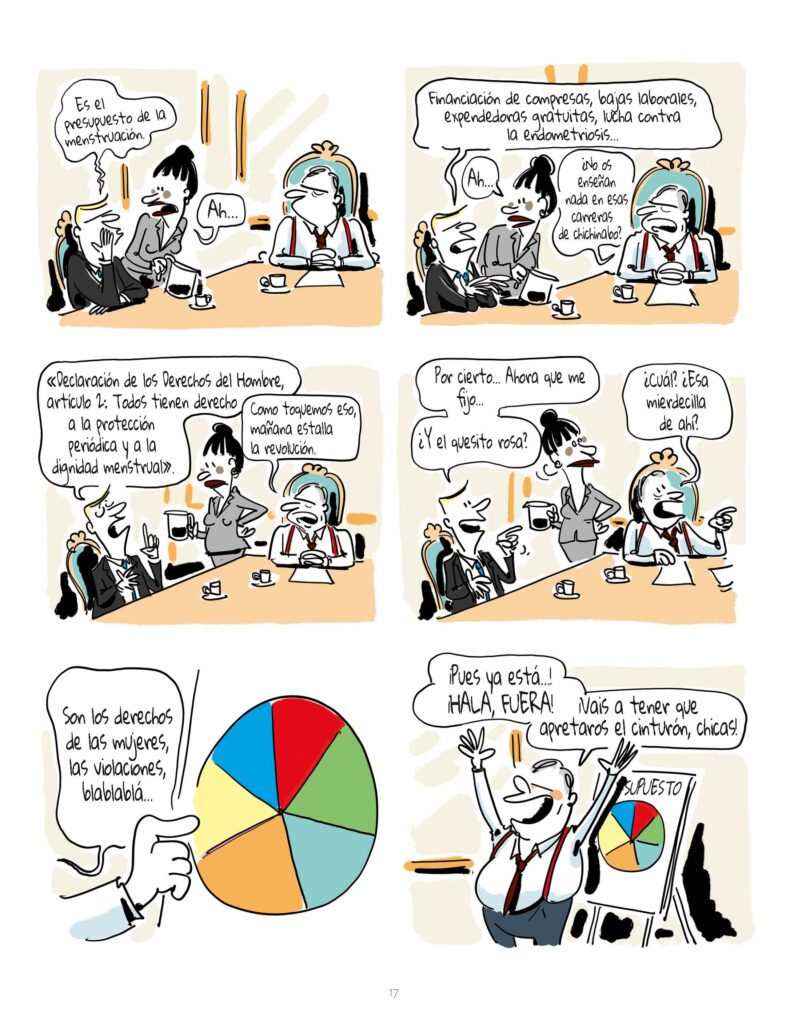

There are a few books dedicated to young people, such as ¨La Regla Mola” by @Anna Salvia Ribera and “Welcome to your period” by Yumi Stynes, Dr Melissa Kang and Jenny Latham. I would also like to highlight this new adult book, “Si les hommes avaient leurs règles” by Éric Le Blanche and Camille Besse. This comic explores an amusing hypothesis based on deconstructing the taboos surrounding the menstrual cycle. According to their authors, if only men got their periods, then menstruation wouldn’t be the shameful physical manifestation that it is for so many women across the world. On the contrary, if it were a male characteristic, then menstruating would be a sign of pride, a mark of masculinity even, and not getting your period would be what’s stigmatizing.

For more resources and support, please find below different organizations and activists locally and globally fighting for improved menstrual health education in primary schools. Those are only some of them. For more information, do not hesitate to contact them.

- Asociación de Cultura Menstrual ´La Vida en Rojo Carolina Ackermann Barreiro (Cataluña)

- Period Spain Mireia Pérez-Sabadell (Cataluña)

- Menstrual Point® (Cataluña)

- OudOca pedagogía menstrual Patricia San Mateo Hidalgo y Lila Arsuaga Méndez Cataluña)

- Ciranda @Júlia Sànchez y @Natacha Fabregat (Cataluña) Menstrualmente Hablando Nora Pascual (Navarra)

- Amba, Menstruación Digna @cristina rubio Cristina Rubio (Madrid) Heygirls (UK) @Celia Hodson Obe

- ThePadproject (USA) Melissa Berton

- We Bleed Red Movement (Philippines) Gianinna Czareena Chavez Full of Life Trust Initiative (Zimbabwe) Rachel Nyasha

- Menstruacion digna UNAM, (Mexico) Monica Quijano Velasco Heshima Ya Binti (Dignity of a Girl) project (Kenya) Angela Ifunya

References

[1] Sánchez López, S., Barrington, D.J., Poveda Bautista, R. and S.E., Moll López. Spanish menstrual literacy and experiences of menstruation. BMC Women’s Health.

[2] Rivera-Cazaño CV, Diaz-Blas PA, Cavero Paredes C, Tejada-Flores J, Cuya Palomino KB, Osorio-Delgadillo R. Efecto en la andropausia y menopausia del Lepidium meyenii: Una revisión de la literatura. Rev. Peru Med. Integr. [Internet]. 30 de diciembre de2023 [citado 27 de julio de 2024];8(4). Disponible en:

https://rpmi.pe/index.php/rpmi/article/view/76.

[3] Iglesias Benavides, José Luis (2009) La menstruación: un asunto sobre la luna, venenos y flores. Medicina universitaria, 11 (45). pp.279- 287. ISSN 1665-5796

[4] https://www.yourperiod.ca/normal-periods/menstruation-around the-world/

[6 ]https://helloclue.com/articles/culture/talking-about-periods-an international-investigation-findings

[7] Iglesias Benavides, José Luis (2009) La menstruación: un asunto sobre la luna, venenos y flores. Medicina universitaria, 11 (45). pp

[8] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226792 [9] https://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/194362

[10] https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g23/049/82/pdf/g2304982 .pdf

[11] https://pcrttz.wixsite.com/home/about

[12] https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/feature/2022/05/25/policy reforms-for-dignity-equality-and-menstrual-health

[13] https://igualtat.gencat.cat/web/.content/Departament/Transparencia/ Gestio-serveis-publics/Plans sectorialsinterdepartamentals/PEM_VERSIO__28_2_23_IFE_SIGOV_ A30_A39_pagina70_DF.pdf

[14] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12978-021-01285- 7#citeas

[15] https://revistas.upn.edu.co/index.php/biografia/article/view/4508

[16]https://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/194362/TFM_2021_PascualArmendariz_Nora.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[17] https://www.65ymas.com/comite-expertos/mujer/mujeres mayores-reaccionan-modo-menopausia-aire-acondicionado-lg-es-

[18] Criado Perez, Caroline. Invisible Women: Data Bias in A World Designed for Men. Harry N. Abrams, 2019

Sandra Ruiz Moriana is a migration and gender expert. In her professional journey, Sandra has developed extensive expertise in the social, humanitarian, and international development sectors. Her dedication to these fields is particularly notable for her gender-sensitive approach, which champions diversity and inclusion.

She is also a regular writer at the National Spanish Newspaper "La Vanguardia", where she shares her insights and expertise on migration, gender, and social issues. To learn more about her, please click on the following link: www.linkedin.com/in/sandra-ruiz-moriana