Fatemeh (Mojgan) Kazemianrouhi, a Persian Iranian living in Paris, shares her deeply personal journey. Coexisting with dozens of other migrants in a dormitory in Italy, she has witnessed and lived through their collective experiences and narratives. Her story is part of a larger, shared narrative that reveals the unseen, ignored, and marginalized issues in society.

by Fatemeh (Mojgan) Kazemianrouhi

I am a migrant, dis’place’d, uprooted, removed. I am not a researcher or a writer, nor a storyteller. I am just a migrant, a living truth, a lived experience.

I am a migrant who has coexisted in a dormitory with dozens of other migrants, witnessing, hearing, touching, and living through experiences, sufferings, feelings, and narratives. I do not look at this story from the outside; I am part of this story; I am my experience.

My narrative is not solely my own; it is our narrative. It is not everything that is there; it is what exists but is unseen—the ignored, the marginalized, the hidden issues that manifest as suffering, violence, discrimination, and more.

As a migrant, I believe every migrant’s story should be heard, giving a voice to the voiceless. These narratives bring issues to light.

As a migrant woman, I have often heard statements suggesting I should form a relationship with a man from the host community to be accepted and to improve my situation as if my existence gains meaning and prominence through such connections. Even if I do engage in such a relationship, it is often interpreted as the main reason for better conditions and residence. In any case, there is a bias against me as a migrant, and these biases are the problems, not the migrants themselves.

At the airport from Iran to Italy, they allowed us to pass in line but stopped an Iranian man, asking him numerous questions and wasting his time. Why? Because of his Middle Eastern appearance? His nationality? His body…

Discrimination revealed itself to me as a migrant from the very beginning, from the first moment of my arrival. I managed to find an internship in the UK, and the manager agreed to my presence. However, he informed me that due to governmental and political restrictions, my visa application had a 90 per cent chance of being rejected. I did not even get the chance to apply for a visa because I was not European! The year before, a girl from the same university worked at the same company without any visa issues because she was European. My acceptance was conditional—on the condition of being European.

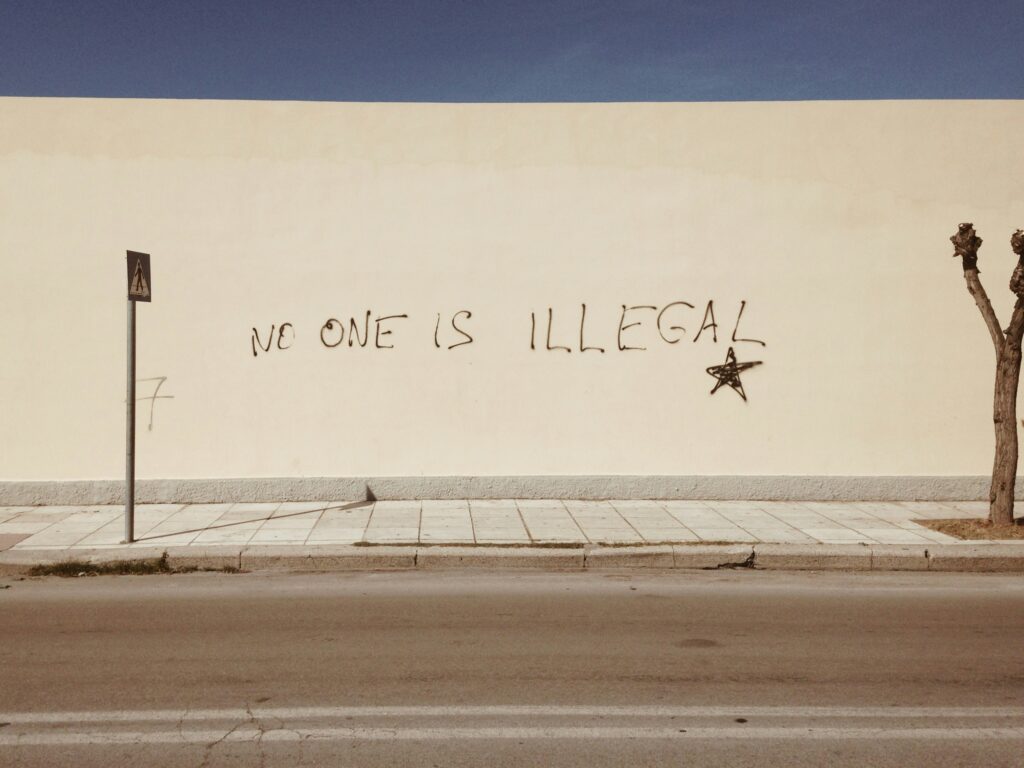

I am not allowed to work or be present in certain parts of this land because of my nationality, on a land meant for all of us to live on. Lost opportunities and missed chances due to policies and laws are the problems, not the migrants.

We know everything goes back to the police, to policies, and that “everything is political,” but why should the words “migrant” and “police” come together, side by side? This is the issue. The presence of a migrant, the word “migrant,” itself becomes criminalised.

For an internship, I went to Paris and chose to travel by train to see the lines, borders, officials, and places. Somewhere on the Italy-France border, we were taken off the train, and security officers stood there, requiring us to show our IDs. They were very serious, strict, and orderly as if these people in transit were under their control. The officer stood seriously in front of me. When I showed my Italian residence permit, and he checked it, his seriousness turned into softness and a smile. He remembered his ‘hospitality’ only then. I am a Master’s student in tourism management. I have read and heard a lot about hospitality, but which hospitality is it? This kindness and hospitality were not because of my presence as a migrant or ‘guest’ but because my documents were approved. In reality, he was kind to my ‘documents,’ not to me.

I found a student job. One day, a colleague, who was quite the joker, laughed and said to me, “Do your job well, or I’ll call the police and say there’s a migrant here.” The police? We know everything goes back to the police, to policies, and that “everything is political,” but why should the words “migrant” and “police” come together, side by side? This is the issue. The presence of a migrant, the word “migrant,” itself becomes criminalised.

A migrant is not a problem; a migrant is simply someone caught in the challenges of time and place, moving from one location to another for various reasons.

A year before graduation, we face the anxiety of finishing our studies, the stress of visas and residence, and the uncertainty of what comes next. These “afters” remain with migrants because migration is continuous and never-ending.

I am always faced with the question, “Do you intend to return to your country after your studies?” It seems the name “migrant” is intrinsically tied to ‘moving,’ from here to there and from there to somewhere else.

A migrant is not a problem; a migrant is simply someone caught in the challenges of time and place, moving from one location to another for various reasons.

I spoke with a migrant in the dormitory who said, “Why is it that when a dog crosses a line or border, it is not judged or expelled, but when a human crosses a border, they can cease to exist, die, be rejected, or expelled?” The issue is the body, not the border itself; it is the essence of being human, the thought, our presence. It is about who or what is allowed to cross.

Our problem is not migrants or borders; the problem is policies, governments, national systems, nationalism, racism, and sexism. Since my migration, borders are no longer lines for me; they are points—points of racism, nationalism, and more—that form an ideological border. Migrants are not the problem; the issue arises from the knowledge that exists against us migrants, from ‘colonial’ knowledge that ignores the voiceless and their feelings, and from the heart of policies. From the reasons for migration to its consequences, everything is political.

Fatemeh (Mojgan) Kazemianrouhi is a 36-year-old Persian/Iranian living in Europe.

She is an M.A. student in Planning and Management of Tourism Systems. She lived in Bergamo, Italy, where she worked in a bar and as a tour guide.

Now, she is in France doing an internship at a hotel in Paris and recently researching migrants' experiences and collecting their narratives.