by Anita Bhadani

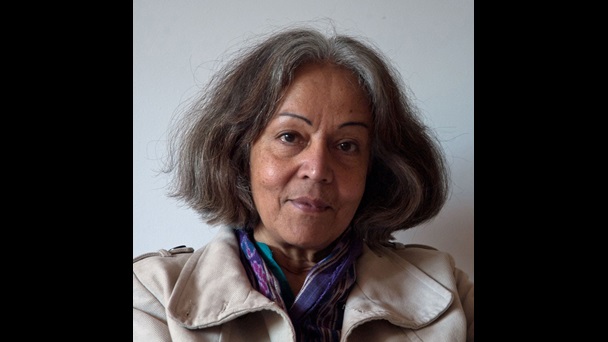

The writer, journalist, anti-racist and feminist activist Amrit Wilson has never shied away from unsettling commonly held realities, tackling head-on the insidiousness of oppressions such as racism and misogyny. She defies both over-simplistic liberal thought and class reductionism, articulating her vision – unapologetically and without compromise. As a young South Asian woman growing up in Scotland, coming across her work was transformational.

Today, as someone quite literally ‘finding my voice’ in the early stages of my journalistic career, it was deeply insightful to have the opportunity to speak with Wilson about her work, activism and insight on the political environment we presently inhabit.

As a young South Asian woman growing up in Scotland, coming across her work was transformational.

“I was born in India at the cusp of India’s independence from British colonialism. So even as a young child, I was aware of struggles for justice and against colonialism and racism going on around me,” Wilson tells me when I ask her about the development of her radical political consciousness.

“On another level, I also gradually became aware of the oppression faced by women in my extended family. My parents, particularly my mother, were unconventional people and fighters for justice on many levels. They encouraged me to think independently.”

Wilson’s independent thought led her to throw herself into the struggle for liberation on multiple fronts. Growing up in India, Wilson moved to the UK as a student in 1961. By 1974 she worked as a freelance journalist alongside being active in anti-racist movements. She was a founder member of Awaz, the UK’s first Asian feminist collective, and was involved in OWAAD (the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent, active between 1978 – 82).

I was born in India at the cusp of India’s independence from British colonialism, so even as a young child, I was aware of struggles for justice and against colonialism and racism going on around me.

Today, she is active in the South Asia Solidarity Group – of which she is a founder member and continues to write on topics from the resistance to Hindutva fascism in India, to the struggle for prison and police abolition in the UK and US.

On the relationship between her journalism and activism, Wilson reflects, “In some ways, my activism came first. I found I could write effectively, so I thought journalism may be a way of contributing to the activism I was committed to.”

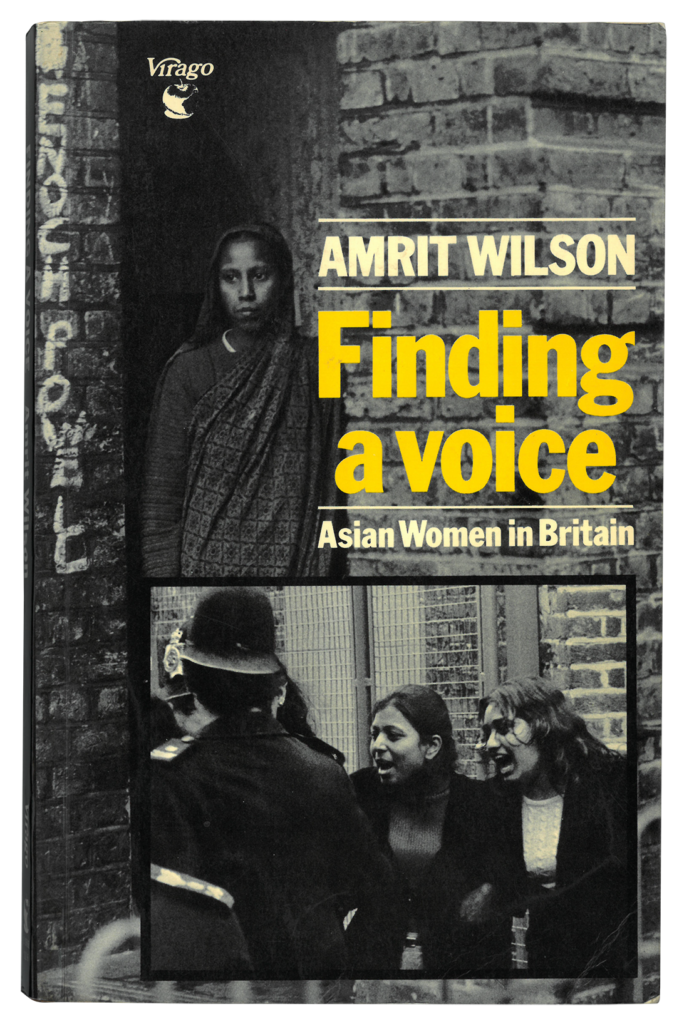

Wilson has authored four books, the most acclaimed of which is Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain, winner of the Martin Luther King award. Finding a Voice brought voices and perspectives from South Asian women in Britain often side-lined to the centre of thought and analysis.

As Sujata Aurora, chair of Grunwick 40, reflects in the revised edition, “Unlike so much of the tired diasporic writing available at that time, Finding a Voice spoke to us as agents of change, rather than as victims of a culture clash. It brought together a material analysis to the notions of ‘duty’ and the structures of family, rather than relying on wholly culturalist explanations for our experiences”.

In some ways my activism came first. I found I could write effectively so I thought journalism may be a way of contributing to the activism I was committed to.

Over 40 years on from its original publication, I wondered what Wilson thinks of the mainstream representation of Asian women in Britain today?

“Basically, some things have changed – others remain the same,” says Wilson. “This is in line with the changes in class position of some Asian groups, the complex nature of the Asian communities, the growth of intense Islamophobia in line with America’s global interests, and course the emergence of neoliberalism and massive corporate power”, says Wilson.

“These factors have reshaped racism as well as gender. The notion that Asian women are victims oppressed by Asian men who can only be saved by white men (often in the shape of the British state) is still alive and kicking and constantly regurgitated by the mainstream media,” she continues.

“This is accompanied by measures like No Recourse to Public Funds, domestic violence laws which exclude protection for migrant women, and a shockingly misogynistic police force, [which] are all factors that directly oppress and endanger women.”

At the same time – and in contradiction to the victim image, and thanks to the rise of acute Islamophobia and growing fascism – Muslim women are being stereotyped as linked to terrorism and attacked the street, while hate speech targeting them is rife; on social media.”

The notion that Asian women are victims oppressed by Asian men who can only be saved by white men (often in the shape of the British state) is still alive and kicking and constantly regurgitated by the mainstream media.

Despite this, Wilson adds, there is still hope to be found and some progress being made. “Many Asian women are out in the public arena as journalists, writers, scientists etc. – and this inevitably helps to expose the stereotypes for what they are.”

Wilson remains active and engaged in the public arena in a wide variety of projects alongside her journalistic practice today. “I am working with South Asia Solidarity Group – a London based antiracist, anti-imperialist organisation. Our work is to amplify the struggles for justice and democracy in the countries of South Asia”, she says.

“We are currently working in solidarity with the movements and individuals resisting the fascist Hindu supremacist Modi regime in India. Most recently, for example, we organised a meeting at the COP26 People’s Summit, which prioritised the voices of Adivasis (indigenous) people of India who are resisting land grabs for coal mining by corporates like the notorious Adani Group.

We have also held mass demonstrations again the imposition of fascistic Islamophobic citizenship laws in India. Also, against the militarization and occupation of Kashmir and the rapes of Dalit women.”

This is accompanied by measures like No Recourse to Public Funds, domestic violence laws which exclude protection for migrant women, and a shockingly misogynistic police force, [which] are all factors that directly oppress and endanger women.

The Marxist and materialist politic Wilson’s work is grounded in resisting the ontologisation of oppression as something static in our communities. It shows that not only can our world and structures be made and remade – but that it is we who hold power to make that change happen.

Asked if she has a message for the next generation of South Asian women – and women of colour more broadly in the UK today, engaged in similar struggles, Wilson replies:

“Don’t lose hope and don’t compromise with the powers that be. The neoliberal state must be taken on and never embraced. And as you resist make sure you care for yourself and your companions – because this is a

hard and demanding struggle, and we must survive in order to resist!”