What happens when a space built for liberation becomes another site of oppression? Performers of colour in Scotland reflect on racism within drag and nightlife and how they’re reclaiming the stage on their own terms.

by Lorelai Patnaik

If someone had told me in 2022 that the Scottish drag scene was a welcoming and inclusive community for a trans woman of colour, I would have naively accepted it as fact. And it felt like that for a while, until my perception was shattered.

When I first arrived in Scotland from India in September 2021, seeking freedom as a trans woman, I looked to drag as a platform where I could perform freely, expressing my art and being myself. At the beginning of my drag journey, the scene felt welcoming; I felt myself growing into a community. I started performing in April 2022, after spending time in Glasgow’s queer co-operative bar Bonjour back in 2021 and feeling at home enough to try the stage.

“In a very white-dominated scene, it’s not always a pleasant experience being a performer of colour.”

I applied for an open stage curated by Tracks Mondays, a drag night in Edinburgh that gave me a platform to showcase my style of drag, which is rooted in my culture and different from what many performers do here. That was when my journey into performance officially began.

Since then I have been performing in venues across Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee. I’ve watched my art grow, made close friends, and found a community. Yet this does not negate the fact that I have faced significant upheavals and barriers as a performer of colour, which, at their core, are rooted in one issue: race. In a very white-dominated scene, it’s not always a pleasant experience being a performer of colour.

Lorelai Patnaik. Photo by Angelo Karle

Frankie/Huntress, a Glasgow-based Irish Filipino artist, who has performed for a decade and DJ’d for the past few years, recognises that feeling of being singled out. She describes experiencing racism early in her career, when there were few BIPOC performers on the circuit and she was often the only non-white artist in the room. Now a resident at EXIT nightclub and a PonyBoy resident artist, she told Migrant Women Press: “I used to work in a gay bar, and once the manager made an offhand comment about some missing tips which in fact were stolen by one of my white coworkers and my boss instead blamed me by comparing me to Aladdin the thief, casting me in a negative stereotype.”

A nationwide survey on diversity in the arts found that Black and minority ethnic artists are still far less likely than white peers to access opportunities, with institutional racism at the core of this inequality. Unfortunately drag, like many other cultural and artistic spaces, is subject to systems of oppression that operate in day-to-day life: racism, transphobia, ableism, and so on.

“My experience so far has been not being booked as frequently as my fellow white peers, frequently being talked down to, being made to feel that my style of drag isn’t ‘Western’ enough, and being made to feel like I’m not ‘fitting in’.”

Scottish drag culture is still very white. Most shows are run by white performers, and opportunities often flow through those networks. For many performers of colour, this shapes everything from how often they are booked to how their drag is perceived.

My experience so far has been not being booked as frequently as my fellow white peers, frequently being talked down to, being made to feel that my style of drag isn’t ‘Western’ enough, and being made to feel like I’m not ‘fitting in’. These moments chipped away at the confidence I had built.

Hagi from Ponyboy Clubnight Photo by Spit Turner

Hagi, a Mongolian pole, drag and performance artist based in Glasgow, shared: “It was only when I performed for the first time at a QTIPOC-led cabaret that I began getting noticed by other show runners.” Hagi explained that it was only when a POC-led show gave them a platform that they got opportunities from white-led shows. “It was my own community that offered me the first opportunity, and helped me for the first time to have a platform as a performer.”

Hagi’s story resonated with me, because it shows how often we have to build our own stages just to be seen. But even when you do break through, you’re not necessarily safe.

“It was my own community that offered me the first opportunity, and helped me for the first time to have a platform as a performer.” Hagi

The most shocking experience for me was seeing a screenshot of a private chat circulated online, which portrayed me in a racist caricature made by a fellow drag performer, which labelled me a terrorist. This was a photoshopped image of me in my traditional attire, an anarkali, from an old performance photo onto a Legally Blonde poster, with added images of bombs falling around me, and titled as ‘Legally Bomb’. This graphic form of racial harm left me devastated. It was like someone graffitiing a racist slur on my house just because I’m a south Asian woman. What is meant to be an art form and essentially a way for community building and forging a safe space has instead turned into another hostile space for the most disenfranchised queers, especially people of colour.

Anti-racism demonstration. Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash.

Ongoing concerns about racism and discrimination in Scotland’s drag scene

In 2024, just before Pride month, posts circulated on X (formerly Twitter) about a Scottish drag show where a performer was alleged to have used discriminatory language. One widely shared clip from the night was too dark to verify, but it circulated alongside allegations of a racially derogatory term targeting South Asians.

In a separate post about the same show, another performer said they had been addressed with an anti-trans slur during the live performance.For many performers of colour, this moment felt like a rupture, a public exposure of dynamics they had long experienced privately.

Soon after, screenshots circulated online including posts shared on X that appeared to show group chats between Scottish drag performers containing racist and ableist remarks. Many PoC, trans and disabled performers used the moment to share their own experiences of exclusion and hostility in the scene.

What mattered most was not just the alleged content of the screenshots, but how it confirmed the issue many marginalised performers had been raising awareness of for years.

A Scottish Government report showed that non-binary people face discrimination across many areas of life, but the experiences of global majority communities are still often overlooked. Where racism and transphobia intersect, the impact is sharper and felt most acutely by trans and non-binary people of colour.

Across the UK, TransActual UK’s Trans Lives Survey (2021) reported high levels of harassment and workplace discrimination. It found that 85% of trans women had experienced transphobic street harassment from strangers, and that Black people and people of colour reported higher rates of transphobia at work, including from colleagues.

Lorelai Patnaik. Photo by Angelo Karle

How performers of colour face racism in drag and the ways they are fighting for change

Hagi further highlighted that “over the years I’ve been performing, I’ve become highly selective of where I perform, and prefer to work with POC led shows, as compared to shows led by white people. I have felt like a token, at times a spectacle in white-led shows, and I felt alienated, from the show runners as well as the audience”. Hagi’s experience reveals that racism in the scene can be alienating and systemically excludes performers of colour from having a platform on their own terms.

Frankie explained that after 2020, a shift took place when she became part of Bonjour, a queer co-op bar and crucial pillar of Glasgow’s queer community and nightlife. She described how she worked with Bonjour to ensure it was a platform that supported disadvantaged artists, especially QTIPOC artists, many of them finding their paths at this significant space, giving these communities a platform.

“It was crucial for white people to take action. To show solidarity. Actively supporting artists of colour, showing up to their shows, donating wherever possible.” Hagi

Platform, community, and support, as highlighted by Frankie, can make a difference. From a time when there weren’t many opportunities for artists of colour, and consequently not many of us on stage, we are now slowly reclaiming these spaces building community. But it is important that white performers are also accountable. Hagi said: “It was crucial for white people to take action. To show solidarity. Actively supporting artists of colour, showing up to their shows, donating wherever possible. And also practicing mindful inclusion as show runners. To book a diverse cast, where POC aren’t mere tokens, it must be inclusive of various body types and disabilities.”

Asli. Photo by Jock Thomson

Asli 007 aka DJ Kaluun, a Somali trans woman, spoke candidly about the importance of community, her journey in ballroom, her experiences as an organiser, a performer and a DJ. “Ballroom was how I found my first sense of community, my first step in engaging with the world as my real self, of finding people I can connect with.”, she said.

“Community gave me agency.” Asli

Ballroom has roots in Black and Brown trans communities, shaped as a space away from racism, transmisogyny and transphobia. Founded by Crystal LaBeija in the 60s, it emerged as a refuge from exclusion in wider white-dominated pageant and drag circuits. For Asli, attending balls and walking categories offered a community, friendships, and a place to grow into herself. “Community gave me agency,” explained the co-founder of Serve, a queer Black-led club night and community event run with Luiz.

Asli also organised a ballroom function back in October 2025, the OTA function Bite Night, a community celebration of ballroom and, most importantly, the communities it’s rooted in. After speaking to Asli, it feels like the answer lies in building a stronger sense of community, cherishing our connections, and protecting the safe space we value.

Exhale.group event activity. Photo by Mahasin Ahmed

The way forward: Creating safe space for QTIPOC+ communities to dream, explore and connect

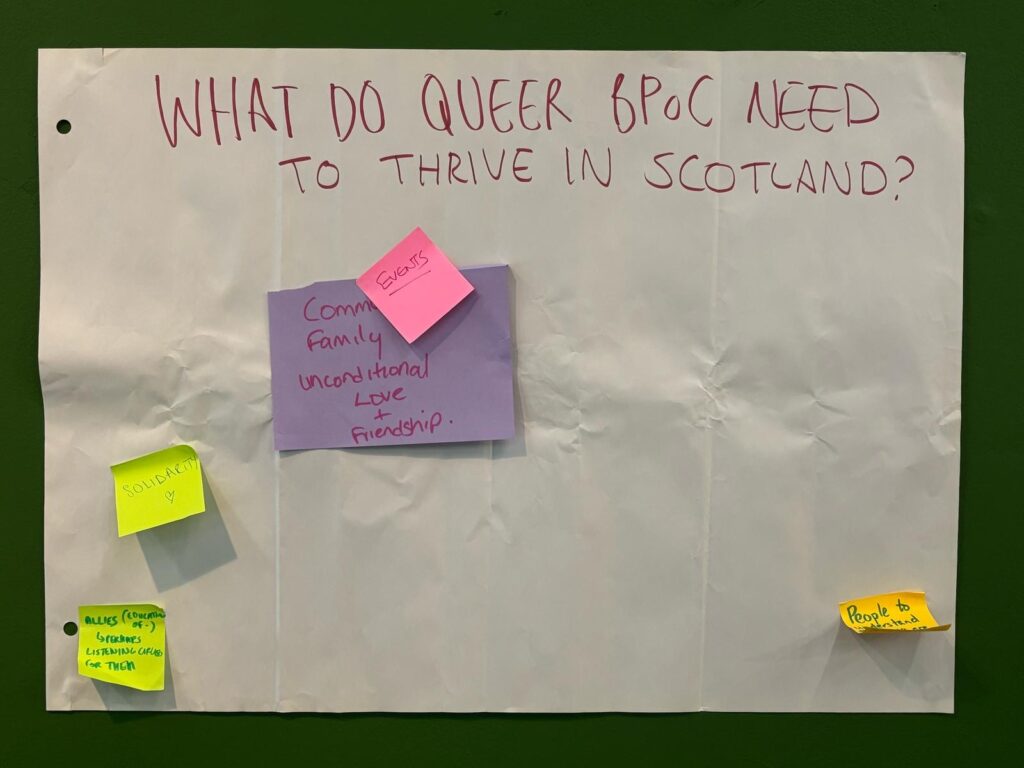

Community-led spaces have become one way performers are trying to build what mainstream venues don’t always provide. Mahasin Ahmed, a community organiser, founded non-profit Exhale.group CIC to create sober spaces and support for Queer BPoC in Scotland.

“I set up Exhale at the end of 2022 as a response to the lack of sober community spaces for us that existed outside of nightlife,” Mahasin said. “I felt a personal need for such a space, as a Queer PoC who didn’t feel totally comfortable in other LGBT+ or BPoC focused spaces because of the intersection of my identity. I thought if I felt this way, there must have been others in the community that did too.”

“I think spaces can’t be 100% safe but there is definitely a lot you can do to make it feel safer.” Mahasin

Mahasin also emphasised that no space can be completely safe but organisers can reduce harm. “I think spaces can’t be 100% safe but there is definitely a lot you can do to make it feel safer. Things like having community agreements in place so people know what’s expected of them in the space, but also to know that there will be accountability if things go wrong. The way a space is facilitated is also extremely important – as someone holding space for people, you need to make sure everyone feels included, inviting quieter voices in, and recognising dynamics in the room and trying to shift imbalances.”

Across interviews, one theme came up repeatedly: online discussions about racism in the drag and nightlife flare up dramatically, but little changes behind the scenes. Apologies, statements and social media discourse rarely translate into shifts in booking practices, safer working environments or meaningful accountability.

Sculpture by Josie Ko displayed at Govan Project Space in 2024 at one of Exhale events.Photo by Malini Chakrabarty @shefilmsthedream

For many performers of colour, these moments highlight the gap between the public image of Scottish drag, playful, progressive, radical, and the private realities people navigate backstage.

QTIPOC+ people continue to face discrimination even within the wider LGBTQ+ community, and remain largely overlooked in Scotland’s equality landscape, with little research, legal recognition or structural support for those experiencing intersecting discrimination.

“Despite the worrying political climate in the UK, I believe community spaces can be a force for our collective resilience as long as we support one another along the way and stay true to our roots”. Mahasin

Slowly, however, change is beginning to happen “Things have massively improved in Scotland in terms of community representation in recent years. I feel really excited about the future for us,” says Mahasin. “I think the community is strong and well connected and we just need to keep the momentum going. Despite the worrying political climate in the UK, I believe community spaces can be a force for our collective resilience as long as we support one another along the way and stay true to our roots. I see Glasgow, specifically, becoming a real cultural anchor in the UK and that is really being driven from the underground with the efforts of grassroots Queer and BPoC-led artists and space makers”, they conclude.

For a lasting change, we need to think radically about structures around us. Structural change would involve building our communities, uplifting and empowering disenfranchised groups, and having a safe space to grow and flourish. Building a future where the marginalised communities are empowered.

Learn more about Exhale.group here

Cover image by @duffymooncreative

This article was produced as part of the Migrant Women Press Fellowship Programme 2025.

Lorelai Patnaik is a writer and performing artist based in Glasgow, Scotland. Originally from India, she found a safe haven and refuge in Scotland. Having performed drag for the past three years, she’s also a Law graduate, who loves researching into the intersection of art and culture with law and race. Aside from this she enjoys hiking, gardening and baking.