Drawing on her experience of giving birth in Scotland, her work with Amma Birth Companions, and testimonies from migrant and refugee mothers in Glasgow, Azza Abumandeel explores what a fair and compassionate maternity system must look like if it is to support every woman.

by Azza Abumandeel

I arrived in Scotland carrying both a pregnancy and a question I couldn’t yet put into words: Would I be safe here while trying to give life? I had just been granted refugee status. My documents were new; my understanding of the healthcare system was still forming. Every phone call to a GP felt like a test I hadn’t revised for. I was building a life while preparing to become a mother again, both shaped by unseen rules. It was only later, after giving birth in Glasgow and eventually serving as a trustee with Amma Birth Companions, that I began to see how migrant women often learn maternity care not through guidance but through survival.

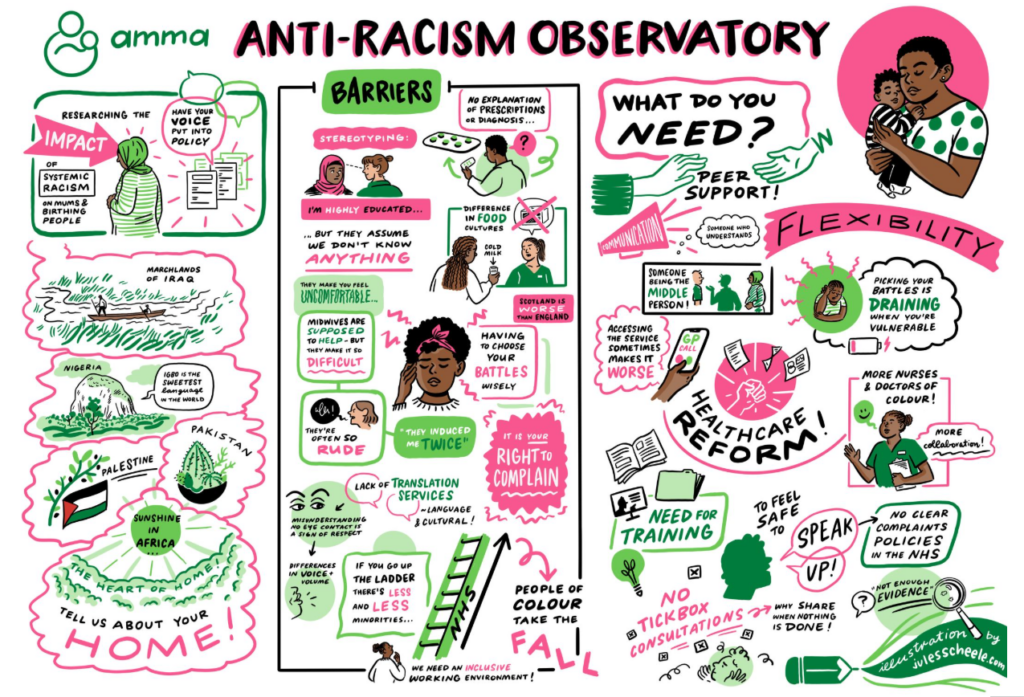

Through my later work with Amma Birth Companions, a Glasgow based charity supporting migrant and refugee women through pregnancy, I began to see how common experiences like mine were for migrant women in Scotland. The charity has supported hundreds of women since 2019, many of whom arrived in Scotland with no local network, no familiarity with the health system, and multiple layers of disadvantage.

Through my later work with Amma Birth Companions, a Glasgow based charity supporting migrant and refugee women through pregnancy, I began to see how common experiences like mine were for migrant women in Scotland

Scotland positions itself as progressive in maternity policy. The Best Start plan outlines a commitment to kind, safe, trauma-informed care. The Women’s Health Plan (2021–2024) prioritises equity in maternal outcomes. Yet Public Health Scotland’s 2023/24 data makes the inequalities visible: 44,383 maternity were recorded, with around 13 percent involving women from ethnic minority backgrounds, who showed higher rates of gestational diabetes, small-for-gestational-age babies, and caesarean births.

Across the UK, MBRRACE-UK reports that Black women remain nearly three times more likely to die in pregnancy or soon after than white women, and Asian women almost twice as likely. Numbers like these demand more than policy ambition; they require proof of implementation in lived experience.

A pregnant woman undergoing a medical visit Photo by Curated Lifestyle on Unsplash

When access exists but arrival is delayed

My first challenge was registering with a GP. I was asked for proof of address I did not yet have. A support worker from a refugee organisation eventually helped move things forward. That delay pushed my first midwife appointment beyond the recommended ten-week window for early screening. I spoke English, but I felt how a lack of language could silence someone more quickly than fear. Some midwives were warm and intentional with their explanations. Others were rushed, using medical shorthand that left me catching fragments of meaning. I asked about trauma-informed care.

Sometimes there was acknowledgement; other times it dissolved in the pressure of time. This mirrors wider findings. Most of Amma’s clients are migrants and refugees, many facing insecure housing, poverty, and the complexities of the asylum system. These pressures increase the likelihood of missed early appointments, gaps in communication, and reliance on overstretched services.

“I felt like a number, not a person.”

A pregnant woman gently touching her belly on Unsplash

Nadine*, in her early thirties and newly arrived in Scotland as an asylum seeker, went into labour around nine at night. Time stretched not as hours but as staff rotations. New faces appeared with different tones but equally limited explanations. She repeatedly asked what would happen next. Answers were partial, transactional. At one point, she was given a glucose drink despite having gestational diabetes that had always been well controlled. She questioned it. A midwife responded vaguely that “hospital ranges are different.” By the following morning, after nearly 24 hours of labour, her baby’s temperature had risen.

She later discovered that not everything she had been given was properly recorded in her notes. “I felt like a number, not a person,” she said. Only when a new midwife took over, one who spoke slowly, looked her in the eye, and explained each step she felt any sense of safety. That safety came from a person, not a process.

“I didn’t refuse. I just didn’t know what I was saying yes to.”

Rania*, a refugee in her mid-twenties, described the day after she gave birth as “hazy”. A midwife told her she would receive “an injection,” using the term “contraception” quickly, without context. Rania, still in pain and dealing with postpartum constipation, assumed it was something to help with her recovery. Only later did she learn it was a long-acting contraceptive that would prevent pregnancy for six months. She and her husband had planned a different method. “She could have used simple words,” Rania said. “She could have asked me if I agreed. I didn’t refuse, I just didn’t know what I was saying yes to.” The issue wasn’t contraception. It was consent given through exhaustion rather than understanding.

A newborn baby lying in a hospital baby bed in a maternity ward Photo by Curated Lifestyle on Unsplash

Pain management is another barrier. Fear around certain interventions is common among migrant women, especially when explained in complex terms. Without culturally and linguistically accessible guidance, choices may be made without full understanding or worse, held against them.

“You chose this.”

Maya*, in her mid-twenties and a first-time mother, decided early in her pregnancy to avoid epidurals or opioid pain relief because she feared potential effects on her baby immediately after birth. As her labour intensified and pain escalated, she asked about other support. A nurse replied, “You chose this. You said no pain relief.” Maya later explained, “I knew what I didn’t want, but I didn’t fully understand all the options.” That sentence, you chose this, felt like judgment rather than care. She laboured on without medication, less out of choice than trapped in a decision she had not fully been supported to navigate.

This stands in contrast to Amma’s values of compassion and person-centred care, which emphasise curiosity, understanding, and non-judgmental support. Maya’s experience shows how far the system still has to go.

Close-up of a newborn baby’s feet on on Andriyko Podilnyk

When maternity care depends on who has time to care

Scotland’s maternity sector is under pressure. Staff shortages, increasing clinical complexity, and rising intervention rates mean that continuity of care which migrant women especially need is often replaced with fragmented encounters. Trauma-informed care is recommended but not consistently embedded. Interpreting is officially provided but frequently inconsistent. Consent is legally required but not always emotionally secured.

Amma’s strategy describes widespread burnout, emotional distress, and unsafe staffing levels across maternity units in Scotland. These pressures help explain why migrant women encounter rushed interactions and inconsistent communication, despite the best intentions of many individual staff members. Birth becomes safe only when someone takes time to build a bridge between explanation and understanding. That bridge is not consistently built for everyone.

Amma Birth Companions volunteers

What change must look like

The women I spoke to were clear about what would have made their care safer. Their experiences, alongside the long-standing recommendations of organisations such as Amma Birth Companions, point to changes that are practical rather than abstract.

“Many of the parents we support are at the sharp end of rising hostility towards migrants, deepening poverty, and widening health inequalities. For women preparing to give birth, these pressures make an already uncertain time even more daunting.” — Maree Aldam, CEO, Amma Birth Companions If equity is truly a national goal, reforms must move beyond aspiration and into accountability. This includes:

- Guaranteed interpreting provision, with clear records of when it is used

- Automatic GP registration support for people living in asylum accommodation

- Early pregnancy booking, tracked by ethnicity, migration status proxy, and language need

- Routine trauma-informed birth planning for women affected by displacement

- Consent protocols judged not only by a signature, but by demonstrated understanding

- Formal partnership with specialist organisations like Amma Birth Companions, built into maternity services rather than treated as optional support

- Staff training that recognises the power imbalance embedded in migrant care

Many of these recommendations have been raised repeatedly by Amma Birth Companions through their advocacy, training, and engagement with national policy processes. What women described in interviews shows why these changes remain urgent.

Birth is often a woman’s first intense encounter with a national system after migration. For migrant women, maternity care can either signal belonging or reinforce marginality. It can say, you are seen here, or it can confirm that safety is conditional, understanding is optional, and consent is assumed rather than earned.

I left my own birth experience grateful for those who made space for my questions, but aware that care sometimes depended on chance, a kind midwife, an available interpreter, a supportive charity not on structural certainty.

The women I interviewed survived their births, but many walked away with lingering doubt about whether they had been fully understood, or fully respected. One woman told me: “They said I had the right to free care. But sometimes it felt like I had to apologise for using it.”

Scotland’s policies speak of equity. Now its maternity system must prove that eligibility is not a technical status, but a lived reality. This is not just healthcare reform but it is about what kind of welcome this country extends to mothers who build their future here, one birth at a time.

This article was produced as part of the Migrant Women Press Fellowship Programme 2025.

*Partial names and identifying details have been withheld to protect the privacy of interviewees.

Learn more about Amma Birth Companions here.

Azza Abumandeel is a PhD candidate in Humanitarianism and Conflict Response at the University of Manchester. She holds a Master’s in International Education and Development from Sussex and a Diploma in Refugee and Migration Studies from University of Oxford. She works at Care4Calais and is a Voices Network Ambassador in Scotland advocating for refugee rights.