Pakistan’s mass repatriation of Afghans threatens to undo the progress of many young Afghan women who rebuilt their lives in exile through education and work. They are now being forced back into danger and uncertainty.

by Ayesha Mirza

In August 2021, when the Taliban seized power in Kabul, millions of Afghans suddenly found their lives upended. Not knowing what to expect, thousands fled to neighbouring Pakistan, either to resettle within the country or move to a third country.

Among them was 15-year-old Zarlasht’s* family. The family left their house in haste, carrying whatever they could. “We came here because my father was worried about the Taliban. He knew the situation would get difficult. We would not be able to study or leave our homes,” she told Migrant Women Press.

Once financially stable in Afghanistan, Zarlasht’s family now lives in a cramped two-bedroom unit in a multi-storey house in Pakistan’s Karachi. The second-oldest of four siblings, she finds herself constantly fearful of returning to Afghanistan amid Pakistan’s intensifying deportation campaign.

We came here because my father was worried about the Taliban. He knew the situation would get difficult. We would not be able to study or leave our homes

But even in Pakistan, Zarlasht’s refugee status has limited educational opportunities for her and her siblings. “I want to become a teacher so I can educate other students like myself,” she said. She currently relies on borrowed books and the goodwill of a neighbour who sometimes tutors her.

Zarlasht’s father, who survives on odd jobs, is forced to stay indoors during police raids that involve arrests and transfers to detention centres. “Our financial situation has tightened (sic) and the future looks bleak. My father is even considering going back to Afghanistan for work while leaving us here,” she added.

Zarlasht’s father, however, worries that without him, his family might be moved to a detention centre and eventually deported.

A long history of displacement

The arrival of Afghans in Pakistan was not unprecedented back in 2021. Pakistan had hosted Afghans for over four decades, beginning with the 1979-1989 Soviet occupation.

Cross-border movement across the Durand Line has continued ever since, particularly during the US invasion in 2001 and again after Kabul’s fall in 2021. According to the UN refugee agency, Pakistan hosts 3.5 million Afghans, including around 700,000 who arrived after the Taliban takeover. At least half remain undocumented.

Despite this long history, Pakistan lacks a uniform legal framework that protects Afghans or grants them citizenship. “The absence of a national policy for Afghans living here creates significant legal challenges,” says Samar Abbas, lawyer and co-founder of the Joint Action Committee for Refugees. In 2006, the Pakistani government and UNHCR jointly issued Proof of Registration (PoR) cards to register Afghans.

The absence of a national policy for Afghans living here creates significant legal challenges

In 2017, the Pakistani government introduced Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC) to document unregistered Afghan nationals. Human rights lawyer Moniza Kakar said that the UNHCR issued tokens to those who arrived in 2021. However, rights activists and advocates said that these documents are not consistently renewed, and authorities within Pakistan dispute their credibility.

Pakistan is not a signatory to international refugee conventions and has not adopted a regulatory framework to safeguard the rights of refugees and migrants. This leaves Afghans vulnerable, as their security depends entirely on shifting government policies. “Afghans are routinely treated as a political football, used as bargaining chips in larger political games.”, Kakar added.

In October 2023, Pakistan launched a three-phase Illegal Foreigners Repatriation Plan to repatriate approximately 3 million Afghans living in the country. In the first phase, unregistered Afghan nationals were given a 30-day deadline to leave the country or face deportation, resulting in over 468,000 Afghans returning to Afghanistan between October and December 2023. The second phase, in April 2025, targeted around 746,000 ACC holders. Within April, roughly 250,000 Afghans returned from Iran and Pakistan. This included approximately 96,000 who were forcibly deported. In July, the government threatened to deport the 1.5 million PoR cardholders who previously held temporary protection.

Art as resistance

18-year-old Ameera* is among a group of Afghan refugee artists whose work was showcased at an exhibit in Karachi on World Refugee Day. Ameera, one of eight siblings, shoulders household responsibilities alongside her mother and often takes care of her younger brothers and sisters. While her parents were not very supportive of her artistic pursuits, this did not deter her. “Ameera is very talented,” shared her mentor, Summaiya Jillani, a visual artist and art educator.

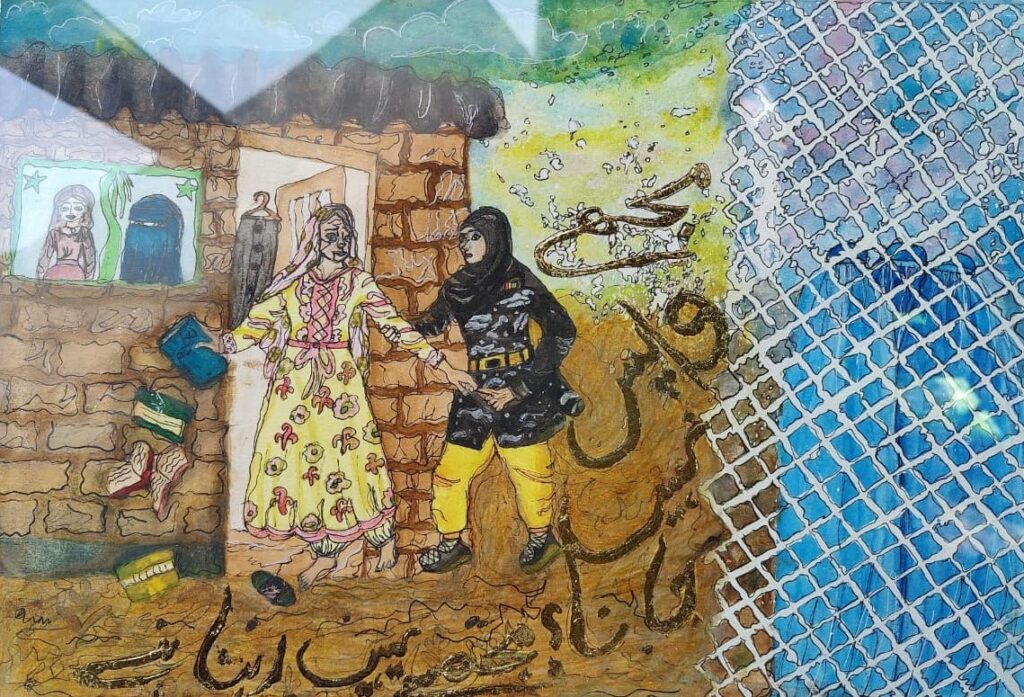

Although Ameera’s family holds a PoR card, she told Migrant Women Press that the government’s announcement to deport even PoR cardholders has left her family under immense stress. Her anxiety was evident in the artwork she displayed: a woman in traditional Afghan clothing being forcefully led away by a law enforcement officer, books slipping from her hands, while another veiled woman watched from behind a window. Across the canvas, in Urdu, were the words: “مجھے واپس نہیں جانا؟ مجھے یہیں رہنا ہے۔” [I do not want to go back. I want to live here.]

In Karachi, Ameera attended a madrassah [religious seminary], but now spends most of her time at home. She was eager to discuss art and future opportunities, but hesitant when the subject turned to Afghanistan. Her eyes reflected the discomfort of returning to a place where she would not even have the little freedoms that she enjoys in Pakistan.

Jillani, who mentored Ameera and other Afghan students, described her experience as both challenging and heartbreaking. She had first conducted a workshop in August 2024, when the situation for Afghans was relatively relaxed. “Back then, I had 25 to 30 female students, most of them Afghans,” she recalled.

The 2024 workshop revolved around sustainability and feminist themes. Jillani said she was struck by how naturally these ideas emerged in the students’ work. “Their stories were already full of suppression and suffering; they didn’t need me to explain what freedom or human rights meant. Their concepts were already very developed; I just taught them the art techniques,” she added.

Their stories were already full of suppression and suffering; they didn’t need me to explain what freedom or human rights meant

The numbers had dropped sharply by the second workshop, which was held between April and May 2025. This time, only 12 to 13 students attended. While Jillani had planned to focus on a smaller group, she explained that many of her most talented students had been deported by then.

One case that stayed with her was that of three incredibly talented sisters who attended the first, third, and fourth classes but disappeared afterwards. “They had shown great interest in the two-month-long course, which was linked to the World Refugee Day exhibition in June,” said Jillani. She was told that the girls had gone into hiding after raids began in their neighbourhood. “They had taken refuge in their uncle’s house, avoiding all public appearances, as authorities were detaining Afghans and taking them to the border,” she explained.

“Eventually, I was told it wasn’t safe for them to step outside at all,” Jillani said. “These were very particular cases, a direct result of the deportation drive.”

While Zarlasht, Ameera, and most of Jillani’s students were recent arrivals, many Afghan families who have lived in Pakistan for decades are also now facing deportation. Peshawar-based journalist Wasim Sajjad and lawyer Moniza Kakar told Migrant Women Press that numerous young Afghan women from PoR-holding families pursued higher education in urban centres like Peshawar, with some going on to pursue law and medicine degrees. Many of them practised professionally, while others were employed across different sectors.

Forced back into silence

Now these women are being forced back to a country that strips them of basic freedoms and systematically denies women their rights. Girls and women who were born and raised in Pakistan must confront an unfamiliar country, one marked not only by climate disasters but also by the Taliban’s escalating restrictions, the most recent being a nationwide internet ban. Many young female returnees also face the risk of being forced into marriages – a concern that Zarlasht’s father also expressed.

Although Pakistan and Afghanistan have increased diplomatic exchanges since April to restore regional ties, the situation for Afghans in Pakistan remains precarious. Many returnees face multiple challenges, as several suffered huge losses in the recent floods in Pakistan. However, they are excluded from government relief because of their undocumented status, explained Abbas. To add insult to injury, those returning are forced to sell their hard-earned possessions at throwaway prices or abandon them entirely.

“By forcibly returning individuals to a territory where they face a real risk of persecution, torture, or inhuman and degrading treatment, Pakistan risks violating a fundamental obligation. For women in particular, the restrictions will make their lives even worse. Many refugees who have been living here for decades no longer have family in Afghanistan, and even if they do, those ties are often severed. This will push women further into isolation from the social sphere,” Abbas added.”

By forcibly returning individuals to a territory where they face a real risk of persecution, torture, or inhuman and degrading treatment, Pakistan risks violating a fundamental obligation. For women in particular, the restrictions will make their lives even worse

On multiple occasions, different entities of the UN have also urged Pakistan to cease forced returns of PoR cardholders and to uphold its obligations under international law and refrain from deporting individuals to places where their lives or freedom are at risk. UN experts also reiterated that the principle of non-refoulement is mandatory.

Afghan families awaiting third-country resettlement also find themselves in a state of limbo. Several of them had begun the process through international agencies or country embassies, but as some countries backtrack on their promises, many now face the risk of deportation without their applications being processed. Consequently, many families have been split apart, with some members forced to return to Afghanistan while others remain behind, hoping their resettlement applications will be accepted. For many women, this means not only separation from loved ones but also the possibility of being sent back into conditions where their lives and freedoms are in imminent danger.

Daily harassment, exclusion from relief, and forced repatriations strip Afghans in Pakistan of both dignity and security. Kakar points out that even though Pakistan has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, it has ratified several international treaties that obligate the state to refrain from treating refugees this way.

Ayesha Mirza is a journalist focusing on social justice, climate change, minority rights, and gender issues.