In a city built on colonial exclusion, today’s migration patterns in Cape Town reveal deepening inequalities, where white Western newcomers are embraced, and Black African migrants are pushed out.

by Tsitsi Bhobo

Hundreds of thousands more ‘affluent’ European (mostly German, Nordic, British) and American tourists, retirees, permanent residents, and remote workers are arriving in South Africa’s Western Cape province, especially the province’s capital city, Cape Town, lured by its Atlantic shoreline beauty, bespoke vineyards, and sunny beaches.

Though the visitors are not grouped by ethnicity, anecdotal cultural observations clearly show that the Western visitors are overwhelmingly white.

Considering this, the largely white-led regional government of the Western Cape Province, which also governs Cape Town City, is aggressively pitching for more Western migrants, both short and long-term, lobbying for more direct flights from Europe and North America, and overseeing the building of a new private airport. What makes Cape Town so attractive to affluent Western migrants is its lifestyle at a bargain price compared to global competitors like Hamburg, London, Lisbon, or Miami.

Photo: Tsitsi Bhobo

The city is now touted as one of the world’s best remote-working gems due to its English-speaking bureaucracy, high-quality infrastructure (in affluent areas, not slums where folks of colour reside), and a South African rand currency, which (at 20 per Euro) is vastly weaker and advantageous for Western migrants.

Hence, the Cape’s rulers are openly declaring: ‘We want their stronger euros, dollars’.

‘Undesirables’

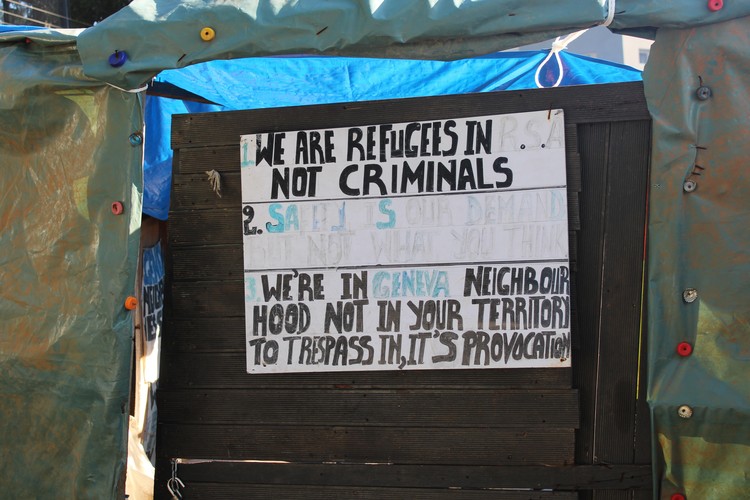

Amidst this glow, poorer Black African migrants, especially refugees from the rest of the African continent, and even Black South African citizens from other poorer provinces, feel they are subtly resented and socially framed as ‘undesirables’ in Cape Town, the ‘most segregated city’ of the world’s most financially unequal country.

“Read between the lines: White Western migrants are lavished with praise in Cape Town. We, African migrants, feel unwanted; in some cases, our very presence is criminalised despite being here longer,” says Bizzy Kaindi, a mum and an asylum seeker from the neighbouring Republic of Zimbabwe.

Kaindi, a former schoolteacher in her native country, now part-time Uber Eats cyclist and activist with the informal grouping Zimbabwe Refugees in Cape Town Alliance, tells the Migrant Women Press of ‘a city that spews a silent air of anti-Africanness’.

There is a caveat as to which type of migrant is welcome to settle comfortably in the Cape region and who is frowned upon, seemingly based on skin colour and privilege.

There is a caveat as to which type of migrant is welcome to settle comfortably in the Cape region and who is frowned upon, seemingly based on skin colour and privilege, she adds. “We are merely tolerated here”. Black African migrants in Cape Town say the city’s governors are hostile to poorer Black African migrants, especially those arriving frequently as undocumented refugees like Kaindi.

In some cases, they are ‘violent to us’, agrees Chilo Bakili, 33, a mum of one from the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. She cites police raids, and subsequent destruction of makeshift street encampments, and even racist rhetoric against all sorts of Black migrants coming to Cape Town and the Western Cape. In 2008, after violent anti-Black xenophobic violence left dozens of victims dead, the Cape High Court ordered that the City of Cape Town open some of its public facilities to house 3,500 African refugees who had been uprooted from the slums of the city. The City of Cape Town vowed to challenge the court order because it would result in scores of African refugees being accommodated in a camp near a popular tourist enclave.

Just a month ago, poorer African migrants said they got a glimpse of this ‘rude’ reception meted out by the Cape government when the municipality pressed ahead with plans to evict 160 refugees living in a large white tent on government land in the Maitland district. The City of Cape Town filed a joint court application with South Africa’s Home Affairs Minister in the country’s High Court to get authorisation to evict some refugees camping out in the open streets. The city wants the refugees to return and ‘integrate’ into local communities, slums from which they ran away, citing violent xenophobia from resentful locals who accuse African refugees of overburdening schools, hospitals, and other public services. “The city dislikes us,” says Tek Mbano, 35, a refugee from Malawi, who clutched his 4-year-old child whilst joining a peaceful protest against the city’s eviction plan.

At the heart of it, says Mbano, the City of Cape Town doesn’t want poor migrants loitering around pristine places that wealthy, white tourists and affluent remote workers frequent or live in. The city’s government says tourism contributes R11 billion ($613 million) to its total economic output. For context, the city’s total revenue in the 2023-24 fiscal year was R62 billion ($3.4 billion).“We are pleading to be relocated to safer countries,” he said. Mbano was among those arrested in 2019 when refugees protested against xenophobia.

‘Right-wing’ rhetoric

The influx (of ‘Blacks’) to Cape Town is ‘too much,’ some right-wing white politicians and residents of the Cape now openly say online on forums like Reddit, lamenting even the presence of Black South African citizens who leave poorer provinces of South Africa to seek opportunity in the wealthier Western Cape province. “End this ASAP!!” a rightwing commentator on Reddit said last year of poorer Black South African citizens coming to the more affluent Western Cape and Cape Town City in particular from severely poor, majority Black provinces of South Africa. “This will continue if they (Blacks) continue to get away with it,” a respondent on the Reddit forum replied, complaining that poor Black domestic migrants will aggressively demand social services like subsidised houses when they start living in Cape Town. Even some of the Cape’s government leaders make indirect insinuations about too many Blacks coming to the region, says Kaindi, the migrants’ rights activist.

For instance, one Ms. Bronagh Hammond, a white woman and director in the Western Cape province’s education ministry, told a public TV channel in December that the Western Cape’s schools were overwhelmed by an ‘influx’ of migrant pupils moving largely from the predominantly Black province of the Eastern Cape. Others, like Craig Phil, a white British man who is thought to be a naturalised South African citizen and leader of the so-called Cape Independence Advocacy movement, are more combative, even planning to go to the White House to lobby for the Western Cape to secede from the rest of black South Africa. The ‘Cape-Xit’ drive mimics the ‘Brexit’ phenomenon of the UK leaving the EU in 2020.

They wouldn’t call it an influx if the foreign students were white, affluent, and relocating from Ireland.

“The Cape government’s rhetoric silently ‘others’ you if you are Black, African, poor; worse, an asylum seeker like me. They wouldn’t call it an influx if the foreign students were white, affluent, and relocating from Ireland,” Kaindi says.

Unrepentant Cape?

Remarkably, a significant number of Black South African citizens (and poor, often undocumented foreign African migrants) sing the same tune that ‘we don’t feel welcome’ in Cape Town. (Usually, poor African migrants and Black South Africans are at each other’s throats over access to the few public services available in South Africa.)

This united Black feeling of subtle, legal, and sometimes violent resentment in Cape Town is not a recent phenomenon, observers say.

Siona O’Connell, at the University of Pretoria, in Pretoria, studies the nuanced reality of displaced people within South Africa and has directed seven films that explore ways of city life after racial oppression in South Africa.

“Cape Town’s complex racial and spatial dynamics tap into long-standing structural tensions,” she tells Migrant Women Press.

Photograph by Kimberly Mutandiro, via GroundUp News (Creative Commons license)

The sense among many Black South Africans—and African migrants—that they “don’t feel welcome” in Cape Town is not a recent phenomenon, even if the expression of this sentiment has become more visible or amplified in recent years due to intensified gentrification, tourism, and spatial exclusion. “Cape Town’s spatial layout and social fabric have been profoundly shaped by colonial and apartheid planning,” she adds.

Colonial violence and who has ‘access and acceptability’ to the city of Cape Town are personal to Dr O’Connell. Her grandparents, uncles, and aunt were forcibly removed to the city’s Hanover Park and Mitchell’s Plain suburbs, which are situated on the Cape Flats, a troubled low-income township. This was at the height of apartheid cruelty from the 1960s to the 1980s. “Seeing my grandfather diminish, becoming a shadow of his former, looming self, has never gone away,” she once told a biographer.

Unlike other metropolitan South African cities like Johannesburg or Durban, which have large, established Black middle classes integrated (however unequally) into the urban core, “Cape Town has long retained an almost Eurocentric, coastal identity centred around whiteness, elite aesthetics, and exclusivity.”

The sense among many Black South Africans—and African migrants—that they “don’t feel welcome” in Cape Town is not a recent phenomenon, even if the expression of this sentiment has become more visible or amplified in recent years due to intensified gentrification, tourism, and spatial exclusion.

After 1994, while the rest of South Africa underwent waves of transformation, Cape Town remained comparatively resistant to demographic and spatial integration. A combination of factors—economic policy, the strength of the white-led Democratic Alliance (which governs Cape Town and the Western Cape Province), and real estate-driven development—has entrenched inequalities that were never fully dismantled. “Black (Africans) and Black South Africans moving to Cape Town in search of work or education often report a persistent feeling of being ‘out of place,’ especially in predominantly white or gentrified suburbs like Sea Point, Gardens, Constantia, or the CBD. Though the city often projects itself as “world-class,” “clean,” and “safe,” these characteristics are sustained by heavy policing, surveillance, and exclusionary zoning laws that disproportionately affect poor Black and migrant communities.

This feeds into the perception that Cape Town is not a ‘Black city’, and arguably never has been—not in spatial, cultural, or symbolic terms. Even townships (slums) like Khayelitsha, which are overwhelmingly Black, remain disconnected from the city’s economic heart, lacking adequate public services, infrastructure, and political clout. The idea that Cape Town is becoming “European” or even “a country within a country” is not just a joke among locals—”it reflects a genuine socio-political divide”, she says.

The city is increasingly becoming a hub for affluent international property buyers, digital nomads, and tourists, many of whom have little engagement with the local population beyond the service sector. Property prices have soared, and short-term rentals (like Airbnb) have displaced long-term residents, particularly in formerly Coloured areas like Bo-Kaap, Woodstock, and Salt River.

Photograph by Tariro Washinyira, via GroundUp News (Creative Commons license)

Many Black Capetonians feel that they “are in the city but not of the city”. The resentment or sense of alienation is not new. Cape Town has long been seen by many Black South Africans as “aloof, conservative, and unwelcoming”. What’s changed is that these sentiments are now surfacing more boldly, amplified by social media, political critique, and the rise of movements. “Cape Town’s un-Blackness’ is, therefore, not just a matter of representation but of access, belonging, and power. It is a city whose colonial bones were never broken, just redecorated”, she adds.

Coded messaging

The Cape Town government dismissed complaints from Black migrants and critics that the city is somehow ‘anti-Black’.

“There is no data to assert that Cape Town is ‘hostile’ to Black South Africans and ‘anti-African’,” Liz Steenkamp, portfolio manager for the city’s Urban Mobility, Spatial Planning and Environment division, told Migrant Women Press.

Even with 2024 data showing that foreign buyers accounted for 40% of all residential transactions over R10 million ($500K) in Cape Town, the statistics of who is buying expensive property in the city do not differentiate between race groups, ‘neither nationalities’, added Steenkamp.

“Cape Town increasingly markets itself as a ‘lifestyle city’, ‘gateway to Africa’, or a ‘world-class remote work hub‘. These are not neutral phrases; they carry strong connotations of “global whiteness, safety, order, and affluence”.

However, O’Connell reads between the lines and forcefully brings into sharp focus what’s left unsaid.

“Cape Town increasingly markets itself as a ‘lifestyle city’, ‘gateway to Africa’, or a ‘world-class remote work hub‘. These are not neutral phrases; they carry strong connotations of “global whiteness, safety, order, and affluence”, she says.

The phrases appeal to European sensibilities and are designed to attract high-net-worth individuals from the Global North, not ordinary Africans or even Black South Africans looking for inclusion, she adds.

No written Western Cape policy explicitly says, “We prefer Europeans over Black Africans.” But an examination of where incentives are directed, who benefits from infrastructure upgrades, who gets lifestyle visas, and who is welcomed as a cultural “fit” reveals a clear pattern that emerges, she says.

“The ‘silent preference’ is enacted through: Economic filters, and cultural coding (Cape Town as a chic, wine-and-design destination)”.

Feautured image Marlin Clark at Unsplash

This story was funded by the Heinrich Boll Stiftung.

Tsitsi Bhobo is a staff writer for The Energy Pioneer and a freelance writer specialising in coverage of Southern Africa. Her work has appeared in Earth Island Journal, The Xylom, GAVI News, The Energy Pioneer, and The Sick Times. For this story, she was a part of the Heinrich Boll Stiftung 2025 Cohort of Transatlantic Media Fellows.