Sahrawi refugee students and teachers take part in a historic summer programme in the UK, building cross-cultural solidarity for a struggle the international community has effectively ignored

by Maxine Betteridge-Moes

I first met Nanaha Bachri in 2022, in the Sahrawi refugee camps of Southwest Algeria, through my work with a UK-based charity, Sandblast. We became friends and stayed in touch via WhatsApp. I saw her again in 2024, when I ran the Sahara Marathon with a group of international runners to raise awareness of the struggle for Sahrawi self-determination.

To see Nanaha for a third time in London this summer, to give her a hug inside a rented apartment in Bermondsey, just around the corner from where I used to live, was surreal.

Nanaha is here with a fellow English teacher, Tarba, and 10 Sahrawi refugee children, who are visiting the UK for the first time as part of a summer programme organised by Sandblast. She told me the visit was surreal for her too.

“We never imagined we would have the chance to travel together to the UK,” she said.

To understand the significance of this visit, and what it took for this small group of Sahrawi refugees to leave the desert camps they’ve known all their lives, we have to go back 50 years. Nanaha, her family, and all the children visiting the UK are indigenous Sahrawis from Western Sahara – a resource-rich desert landscape that lies south of Morocco and north of Mauritania on the northwest coast of Africa.

When the former colonial power, Spain, hastily withdrew from the territory in 1975, it handed power to Morocco and Mauritania, triggering war between the two invading armies and the Polisario Front, which represents the Saharawi people. Thousands of Saharawis were forced to flee chemical bombing in their native land, retreating to the neighbouring Algerian border town of Tindouf to seek refuge and establish provisional camps.

Bachri’s grandparents were among them.

“They had to leave everything behind,” she once told me in the camps over a cup of tea, her eyes darkening. “My grandma only carried a basket with a bit of bread and a bottle of water, with a baby which is seven days old, and five [daughters] that were grabbing her mehlfa [a wrap worn by Sahrawi women] and running from the bombs. There was no time for anything, there was time only to escape with your life.”

Mauritania withdrew from the war in 1979, but Morocco and the Polisario Front continued their bloody battle until a UN-brokered ceasefire was established in 1991, with the promise of a self-determination referendum for the Saharawi people. But the referendum never took place and the ceasefire was broken in November 2020, prompting Morocco and the Polisario Front to resume their armed conflict. This conflict is ongoing, despite little attention from the international media.

Today, nearly 200,000 Saharawis live in the refugee camps, 75% of whom are youth according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR]. A third generation of Saharawis is now growing up in exile, with most dependent upon dwindling humanitarian aid for their survival, amid worsening climate change and with few prospects for a better future.

“For 50 years the Saharawi refugees have lived in limbo, waiting to return to their homeland of Western Sahara,” says Danielle Smith, the founder of Sandblast, who is coordinating the summer programme with the help of a small group of staff and volunteers.

Their visit also coincides with the UK’s recent policy reversal to recognise Morocco’s autonomy plan over Western Sahara – which gives the Sahrawis self-governance under Moroccan sovereignty. The UK had previously said the status of the disputed territory remains “undetermined”. The UK now joins a growing list of Western, Arab and African nations to recognise Morocco’s autonomy plan, placing the Sahrawis’ self-determination cause even further out of reach.

But it is precisely within this context, Smith says, that cultural visits like this to the UK are so important.

“This programme is giving them a chance to fly internationally for the very first time, and to meet other kids from England, to share their story, spark friendships, and build cross-cultural solidarity,” she said.

In 2016, Sandblast launched its Desert Voicebox after-school programme in Boujdour camp, the smallest of the five refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. It teaches four levels of English and music to children living in the camps, whilst simultaneously nurturing their creativity, promoting their culture and telling their stories.

“The children in the refugee camps grow up with very limited opportunities. Desert Voicebox is a unique program that allows them to express themselves through language, music and dancing,” says Nanaha.

The students taking part are graduates of the four-year-long programme, and are now taking part in a series of immersive activities across the UK. The students get to experience different activities like cooking in a shared kitchen, taking a train for the first time, exploring woodland trails, singing around a campfire, painting with chocolate, trying yoga, visiting a zoo, and laughing over language mix-ups. At a hip hop dance workshop in East London, I watched the children giggle endlessly as they used their newfound language skills and universal expression of dance to communicate with their English-speaking instructors.

“London is incredible,” 16-year-old Hanan told me as we walked past London Bridge station on our way back to the rented apartment. “So many different kinds of people, so many cultures,” she added excitedly.

I asked the kids what their favourite activities were, how they liked the cool British summer, and what their new favourite food was. The answer was unanimous: Chinese.

After spending several days in London, the group travelled to Cudham for Camp 100, where thousands of other children from around the world gathered to play co-operative games and take part in educational workshops. I couldn’t help but laugh when Nanaha sent me a voice note and pictures of the camping tents and portaloos on offer – a far cry from the cool and spacious tents many Sahrawis enjoy as part of a traditionally nomadic lifestyle.

“I have never tried something like this in my life,” she laughed. “The tents are very small – you can’t even stand up. But outside is very beautiful and we really enjoyed nature.”

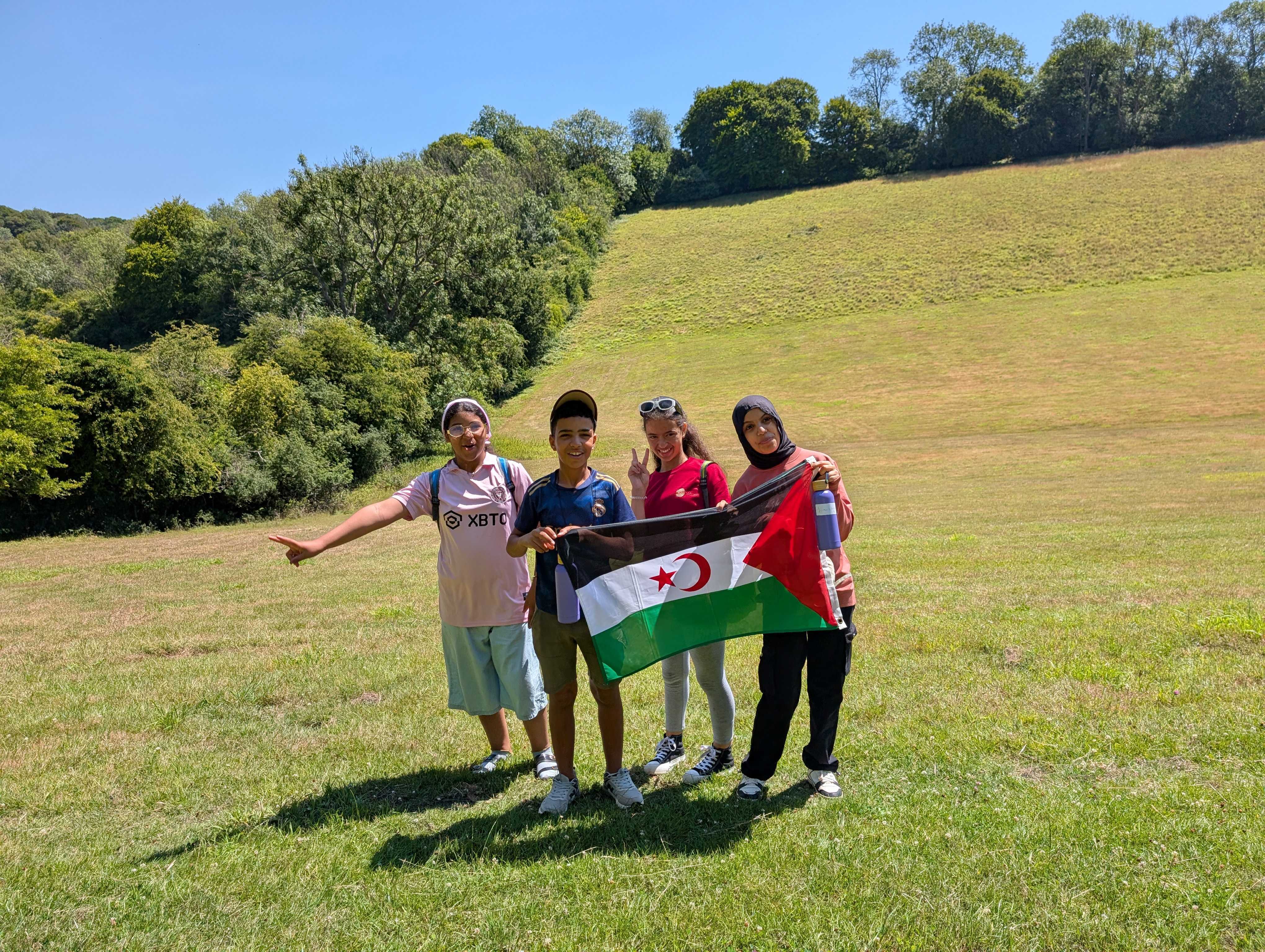

But perhaps the most meaningful moment was when I saw a post from Nanaha on Facebook on their last day at Camp 100. It was a picture of a flag of her home country Western Sahara, planted in the lush green British countryside, with the caption: “Today we saw the flag of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic flying high in the skies of the British Kingdom, in a historic scene that gathered more than a thousand people of the supporters of our people’s right to decide fate. It’s that moment when pride meets hope, and right meets determination. Our flag was raised today in a land that has not yet recognised our rights, but was raised high so that our voice can be heard by the world: we are here, and we will not give up our right to freedom and independence. Thank you to all who stood up for our case and stood for justice. Truth never dies as long as there is someone who demands it.”

Sandblast is hosting a farewell party for the Sahrawi students and teachers on 21 August at Pax Lodge in north London. The event is open to the public, but people are asked to register via Eventbrite by 17 August.

Maxine Betteridge-Moes is the digital editor of New Internationalist magazine. She has been reporting on the Sahrawi refugee crisis and the ongoing occupation of Western Sahara for several years, for publications including The New Humanitarian, The Continent, boom saloon and others.