When immigration and child protection intersect, migrant families can be torn apart. In Scotland, Nina, a mother from Southeast Africa, endured separation and lasting trauma from cultural and racial bias. Campaigners claim her story reflects a wider pattern driving grassroots calls for urgent reform.

by Juliana da Penha and Karin Goodwin

On one side of Nina’s bright living room, life is flourishing. Plants line the large window, green and verdant, the tendrils of one tumbling vigorously down the side of a high shelf. But on the other side, where a small memorial has been set up, time has frozen. Cut flowers and candles gather with some forlorn stuffed toys and photos of the son who was removed from her care as a toddler, along with his pre-school sister. Contact between Nina and her children, who we’ll call Zara and David, was stopped seven months later.

Her son David had been in permanent foster care for years when, still a young teen, he took his own life. The nature of his death meant that the only glimpse Nina was allowed in the morgue was of his hands. They reminded her of the hands of her youngest child, now nine and playing quietly upstairs.

Nina lives in a space between two worlds. Part of her moves amongst the living – caring for her three children still at home, messaging her oldest living in England, childminding, going to church, tending her garden. But, she says, the other part is destroyed by a loss that wells up as uncontrollable emotion and pulsating grief, which threatens to engulf her universe. It takes her to lawyers and support groups and to dark places.

This is also a story with different sides. There is Nina’s version, a mother from Southeast Africa who claims her actions were culturally misunderstood by a racially discriminatory social work system, which removed her children, leading to the seemingly irreversible breakdown of her bonds with two of them.

But then there is the perspective of the foster parents and of Zara, the older sister also removed from Nina’s care, who is now a young adult – all said they did not want to contribute. Zara has been consistent in her refusal to have contact with her mother. To protect their identities – as well as those of Nina’s other children – we have given everyone in this story different names and changed or removed some details.

For Nina’s supporters, some of her claims of racial bias are part of a pattern, highlighted by two new reports by Black and migrant-led organisations in Scotland launched in the last three months. Both offer evidence to support concerns that the child protection system is designed in a way that discriminates against families on the basis of race and culture. Migrant Women Press has teamed up with The Ferret to investigate these long-standing and widespread fears in cross-border work with journalists in Italy and Romania.

Grassroots organisation Passion4Fusion said they had worked with 76 families over the last two years. Most of the cases showed some elements of “racial bias” in terms of social work involvement, they claimed. Edinburgh-based Project Esperanza, which also works with parents and young people, told us they worked with over 40 Black and racialised families and shared similar concerns. Many of them were migrants, unfamiliar with Scottish laws and customs. We also received anonymised details of cases from Scottish Refugee Council and Glasgow-based Women’s Integration Network, which also supports migrant women.

These organisations are calling for reform to ensure more migrant families get support sooner, helping them address problems and raise their children in line with Scottish laws before they escalate to a situation where children are removed from the home.

Most recent Scottish social work statistics suggest that 828 Black and ethnic minority children were in the care system as of July 2024, but there are a further 1,297 children with no recorded ethnicity.

Child protection is one of the most complex and emotive issues, wound-up in love and fear. Scotland’s current policy is that as long as it is safe, families should get the support needed for them to stay together. But social workers also have to be highly attuned to risk. On average, one child a week dies by assault or undetermined intent in the UK, most commonly caused by the child’s parent or step-parent.

In Nina’s case, there are copious but redacted legal notes taken from documentation she provided to her lawyer – covering the period from when she first entered the asylum system until Zara and David were permanently fostered many years later – to help us tell this story. Even the reports don’t all concur. Some raise concerns about her ability to give her children a safe and nurturing home, while others provide clear explanations for her parenting choices, allaying fears.

It is from these we can confirm that Zara and David were born in the UK more than 15 years ago, while Nina was working as a carer for an older woman in the North of England, saving money to send back to two older children back in Southeast Africa who were looked after by extended family. The intention was for them to join her later.

But when the older woman died, Nina’s work visa had already expired. She claimed asylum saying she would be under threat of female genital mutilation (FGM) if she returned home. Within weeks she was confronting the devastation of being refused refugee status. Along with then-baby David and three-year-old Zara, she found herself in immigration detention for more than two months. Several failed attempts were made to physically remove them from the country. She was put on a plane several times, along with her children, sometimes she says, in handcuffs.

It was while in detention that concerns were first raised about Nina’s depressed state. Fears about the impact of that on her children saw them taken into care for two weeks, but then returned to her on the advice of social workers. From there, the family was allocated an asylum flat and sent to Scotland. Notes state that social workers there were alerted and visited from September. They recorded Nina’s seeming “emotional detachment” from her children and difficulty controlling her emotions. Some reports later allege she used physical chastisement. She vehemently denies this, insisting she was never aggressive to her children, claiming she would put David in another room until he stopped crying. Within months a referral was made to her doctor due to the impact of her immigration situation on her mental health.

Now, many years later, Nina remembers this period differently, claiming social services were only alerted when she left one of her small children with a friend while she went to report to the Home Office. It seems odd until she explains: “I don’t know the system. I didn’t understand the language. We don’t have social services in my country.”

She does remember the way her world fell apart when, more than a decade ago, they were removed from her care. “I felt like my kids were dead,” she says. “When your child is missing you think about them constantly. What are they eating? Are they sleeping? Are they crying? You feel completely helpless, completely hopeless. All you want to do is get them back with you.”

At night she could not sleep. Perhaps, she thought, the police would help her. She left the house after midnight, the empty streets blanketed in snow. “But I wasn’t cold,” she remembers. “I just kept walking, thinking about my kids, how I could get them back.” At the police station, she begged them to return them and threatened to harm herself if they did not. In her pocket, they found a knife. She was arrested for possession, a charge the court later threw out. But it remained on her notes like a stain, evidence of her “erratic and unpredictable” behaviour. “They tried to say I was dangerous,” she says. She self-referred to a psychiatric hospital, where her highly distressed state was assessed to be reactive to her situation. No mental illness was diagnosed.

During this time supervised visits to her children were allowed once a week. In her anxious state she fretted about their care, worried about the care of their Black skin and African hair. She was allowed to shave David’s head and given a limited time to braid Zara’s hair. “I never got to finish it,” she says. “Our African hair needs to be cared for properly.” She worried about them developing a scalp infection, which is more common among African children, meaning proper hair care is needed.

When the social worker left the room during her final visit she shaved Zara’s head too.

To Nina, this simply didn’t seem problematic. “That is so normal for us,” she says. “Me and my sisters always had our hair like that. You look at primary schools in my country and you could not tell the girls from the boys.” Now she concedes her daughter hadn’t grown up in Africa: “She wasn’t ready for that,” she acknowledges.

But to the social worker, who walked back into a room with two distressed and frantic children and a then unrepentant mother, a line had been crossed. Contact ended that day. Nina’s distraught daughter told social workers she didn’t want to see her mum again. And she didn’t.

When your child is missing you think about them constantly. What are they eating? Are they sleeping? Are they crying? You feel completely helpless, completely hopeless. All you want to do is get them back with you.

But this backdrop meant that when, just months later, Nina’s two older children arrived from the African country where they were born and lived with extended family, they were immediately taken into care. Authorities said there was no evidence that Flora and Shelton, as we’ll call them, were her children and sent for DNA tests. But though these were a positive match, they were not allowed home. Flora, staunch in her support for her mother even as a young teen, got the bus from school to her mum’s every day and had to be repeatedly returned to the children’s home by police. “That was traumatising,” says Nina. “Luckily, my daughter is incredibly strong.” It inspired Nina’s growing sense of defiance. And something else was growing inside her.

Her new baby arrived with the new year and Nina named her Adira – ‘strong one’. She needed that strength, Nina says. Her baby’s name was already on a pre-birth child protection register and within days, she too was removed from her mother’s care due to the previous concerns. But this time it was different.

“They gave me a new [social work] team this time,” explains Nina. “I felt like these social workers could see the real Nina. I said to myself: ‘God is good’.” For nine more months she was allowed supervised visits with her baby. Notes record her delight in her daughter at this time, who she would sing to as they played.

Meanwhile independent assessors, commissioned by social work, re-examined all the records, read-up on theories about cultural misunderstandings and racial bias in child protection cases and interviewed Nina, her GP and Zara and David’s foster carer. Their observations of Nina’s parenting were based on 30 hours of visits she was allowed with her new baby over that time.

Their subsequent report was balanced but transformative for Nina. It noted she had “some difficulties” in her care for Zara and David and acknowledged the allegation – denied by Nina – that she may have used physical chastisement, though they found nothing to prove it. But it also mentions videos showing happy times with her “lively and bright” children before they went into care. It concluded concerns that David was developmentally delayed due to her poor parenting were, in fact, regression due to the trauma of “his abrupt separation” from his mother. It found “no evidence” that she had struggled with parenting prior to the children being taken into care, when her mental health deteriorated. It refuted several allegations of poor parenting stated as fact in children’s panel hearings.

It suggested she had been culturally misunderstood over issues from the care of African hair to her way of expressing emotion. Assessors wrote: “behaviours when taken in the context of Nina’s nationality and culture are immediately less alarming” and that an understanding of them would allow for “intervention in a culturally sensitive manner”. It recorded the way relations had broken down between Nina and her then social worker. While Nina had previously been untrusting of social workers and officials, assessors experienced “a level of honesty and openness not previously observed”.

They recommended her baby be returned to her care, with ongoing support from social work, and that her oldest daughter Flora went home too, because she had been so vocal about her desire to. They noted they would need to interview Shelton to have a view on his future. However, the relationship with Zara and David in foster care had been “fractured by the separation”, they wrote, noting that ”extensive work” with mental health professionals was needed to repair it.

To Nina, the assessment exonerated her. “If I hadn’t had my baby they would say I was still a dangerous person who was not allowed to have kids,” she says. “It changed everything in every way possible.”

It is difficult to get definitive figures on the number of children from Black and racialised families taken into care in Scotland. Official Scottish statistics show only 82 percent of children in care in July 2024 were white, though a higher proportion – 89 percent – made up the general population of under 18s in Scotland. But for a further 11 per cent of those in care no ethnicity was recorded. In England it is a legal requirement to record ethnicity. In Scotland it is not. English research shows Black children are more likely than their white or Asian counterparts to be taken into care.

The Ferret and Migrant Women Press tried to get figures for the number of migrant children taken into care in Scotland over the last five years. Only nine local authorities provided figures, with six claiming no children had been taken into care.

West Lothian’s figures were far the highest with a total of 42 migrant children taken into care over five years, including 12 children from Nigeria, eight from Poland and eight from Romania and Slovakia. Two were taken into care at birth. Though some cases were “ongoing” none of those children had been adopted.

Five councils, including Edinburgh, refused to give details due to the small number of children involved, which they argued could identify them. But 11 out of the 32 local authorities – more than a third – said they did not record data on whether children taken into care were migrants or not.

“While information on nationality and ethnicity may be provided on a voluntary basis, where this is the case it is often only contained in observational notes and may not be provided at all,” admitted Glasgow City Council, Scotland’s largest local authority. Dumfries and Galloway council added: “We don’t have anything on our system that would help us identify these cases.”

Because in our experience when Black people get into this system they don’t get the same support as white people and they are considered high risk – Helene Rodger, chief executive of Passion4Fusion

Concerns about the disproportionate intervention of social work in Black families across Europe are long running and widespread. In 2021 the BBC reported on the case of a Nigerian victim of trafficking, living in an Italian migrant shelter, who was threatened with having her son taken into care. Those running the shelter were apparently concerned by her so-called “African” ways of bringing up her son, which included carrying him on her back and encouraging him to eat by putting food in his mouth. The 2023 Indian film Mrs. Chatterjee vs Norway documented the real-life story of Anurup Bhattacharya and Sagarika Chakraborty, an Indian immigrant couple whose children were taken away by Norwegian authorities in 2011. Other cases have been documented in Sweden.

Conversely there have been concerns about the way fears of raising the issue of race can prevent abuse being acted on. The murder of eight-year-old Victoria Climbié from the Ivory Coast twenty-five years ago, by her great aunt and her boyfriend, is said to be instrumental in current social work practice. But some claim that understandable fear has led to prejudice.

Helene Rodger, chief executive of Passion4Fusion, which supports families in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Midlothian, West Lothian, Dundee and Fife, says the situation is complex. She explains: “A lot of the families we support come to the attention of social services due to physical chastisement.” She doesn’t excuse it but says it needs to be seen in context. “In a lot of African countries it is quite normal for it to be used as a form of discipline, not harm,” she adds. “We parent how we were parented and that is how most of us were disciplined. In Scotland it’s only been illegal since 2020. Often it’s teachers or neighbours who contact social services.”

One family the charity is supporting have had three children taken to separate white foster carers for this reason, split from their siblings, she explains. But she also shares details of cases where their advocacy and support early on has helped social workers to understand their cultural contexts, led to problems being addressed and seen children returned home.

She claimed migrants should be given clearer information and an opportunity to learn about parenting in Scotland so they know it is against the law to smack their children. Social workers should be trained to better understand the different cultural contexts, she said.

Ensuring early and non-judgemental support is key, she claims. “Because in our experience when Black people get into this system they don’t get the same support as white people and they are considered high risk,” she says, meaning their cases will be judged as requiring intensive support and child protection involvement. “There is no opportunity for failure.” English research backs her experience.

As part of its report, They Took My Child Too – launched at the Scottish Parliament in May – Passion4Fusion surveyed over 100 parents, community members and professionals with experience of the social work system. Almost three quarters believed that there was a “culture gap” for families and social work, while 93 per cent “agreed or strongly agreed” that more culturally aware and sensitive child protection services would improve the welfare of Black and brown children.

“We cannot fix what we refuse to name,” Helene Rodger told a packed room at the May event. “There is racism in the care system.” Recommendations included mandatory anti-racist and cultural competency training for social care workers, foster carers, and child protection decision-makers, along with increased recruitment of Black foster carers and social workers.

Nina’s baby came home after that life-changing assessment. African-born Flora and Shelton were also returned to her care. Flora, now in her mid-twenties and working as an engineer, remembers the relief of that decision.

“We just wanted to be with mum,” she says. “If there hadn’t been that assessment everything could have been different. She is not an evil mother. She was just trying to look after kids in the way that was normal in her culture.”

Nina still aspired to have all her children at home, or at least have contact with the other two. Yet Zara remained adamant that she wanted to stay with her foster family and did not want to see her mother. Nina finds this hard to accept.

According to the Passion4Fusion report this scenario is not uncommon. It claims many Black and racialised children in care “express reluctance or resistance to reconnecting with their families or communities of origin”. Rodgers points out that many of the families she works with are living in poverty. In foster care children have warm homes, their own rooms and parents with more disposable income.

But what Nina really can’t understand is why contact did not start with her son, whose views on seeing her, she says, do not seem to have been fully explored. Notes suggest that while his view on seeing his mother was not consistent, he was sometimes receptive to gifts, photographs and letters she sent him. An increasing level of research suggests even when children are adopted, contact with their birth families boosts wellbeing.

She is not an evil mother. She was just trying to look after kids in the way that was normal in her culture – Flora.

Several years ago the local authority that removed Nina’s children from her care successfully applied for a permanence order for Zara and David, which meant Nina lost parental rights. They remained with their foster carers. Nina kept working with lawyers to fight the decision. She was granted asylum, got a job and registered as a childminder, contracted by social services to look after the children of others. “I was always working and planning for the time when they would come, when we would all be together,” she says. Flora too wanted to contact her fostered brother and sister and got her own lawyer. Since July 2021 the right to sibling contact has been part of Scots law but Migrant Women Press and The Ferret understand Zara refused contact.

Then one day, there was a phone call from social work. “They said they wanted to speak to me about my son,” Nina says, who claims she immediately knew something was wrong. “I was so scared.”

When the police arrived she broke down and fell to the ground. “All these years I was fighting and fighting to see my boy and they didn’t want to know me, wouldn’t speak to me. And now they are at my door to tell me he is dead?” She is crying, wiping tears away as her voice gets faster and louder.

Flora never met her younger brother. Previous work by The Ferret has found that since 2021, 11 young people in the care system have completed suicide, the most common cause of death in this group.

Nina claims she wasn’t welcome at the funeral, but she did attend with friends and supporters. The Ferret and Migrant Women Press have seen a video of her deeply upset, screaming and crying during the service. She is a grieving mother. Not in view are foster parents and a sister, also grieving. This is not a story in which anyone wins.

Victoria Nyanga-Ndiaye – founder of Edinburgh-based charity, Project Esperanza – is currently working with over 40 migrant families with child protection involvement. She claims the way to improve the situation is to make the system less hostile. “It’s designed for hardship,” she says. “Even if you’re white, it’s not fit for purpose. But when you are Black or brown there is a whole other dimension.”

Yet she sees signs of hope. “I’m starting to hear statutory bodies saying, ‘yes, we have got it wrong’,” she says. It’s not been easy work – she claims she’s had to “bulldoze” her way into meetings, and been on the receiving end of awkward silences, and cold shoulders. Very senior managers have even cried over their discomfort when confronted with conversations about race, she claims.

But after years of effort, she’s beginning to see change.

When we see Nina again she is in her lawyer’s office. Some days, like this one, feel very heavy. Jelina Berlow-Raham, her legal representative, is working with her to push for a fatal accident inquiry. The Crown Office will not make a decision on this until its ongoing investigation into David’s death is complete. “There are many questions about his death that still need to be answered,” Berlow-Raham explains.

Nina knows that while having the inquiry might help, it cannot change the inescapable. “Once my life was a normal life,” she says. “And now my son is dead. I feel like he was kidnapped, tortured and killed by social services. It feels like there is no accountability.”

A spokesperson for the health and social partnership involved said it is “committed to practising in a culturally sensitive manner which reflects and values the cultural diversity of [the local authority]”. “Our position remains unchanged,” they added. “[The local authority’s] children should be in their own homes, families and communities and we have invested significant resources in support to achieve this. There are, however, some circumstances which mean that it is not safe for children to live at home.”

But to Nina, whatever the legal paperwork says, David was her son. She carried him inside her for nine months as he grew. “And when he was a baby I would carry him here, on my front.” She places her hand to her heart, where she tied him to her chest in his sling.

People say we are in a modern country where the laws are working. But the laws don’t work for people like us – Nina

“What went wrong? What was happening that nobody could see? Those are the questions I want answered.” This system, she says, has to change. “People say we are in a modern country where the laws are working. But the laws don’t work for people like us.”

There will be other versions of this story. If a fatal accident inquiry goes ahead some of those will also be told by lawyers and expert witnesses. But this one is Nina’s.

Later, she will get in her car, hoping she can get home before tears overwhelm her. She will make dinner for her younger children. On Sunday, she will go to church. When it stops raining, she will take the children to the park or tend her garden where a single red rose is in bloom. One part of her goes on living, the other is frozen in time.

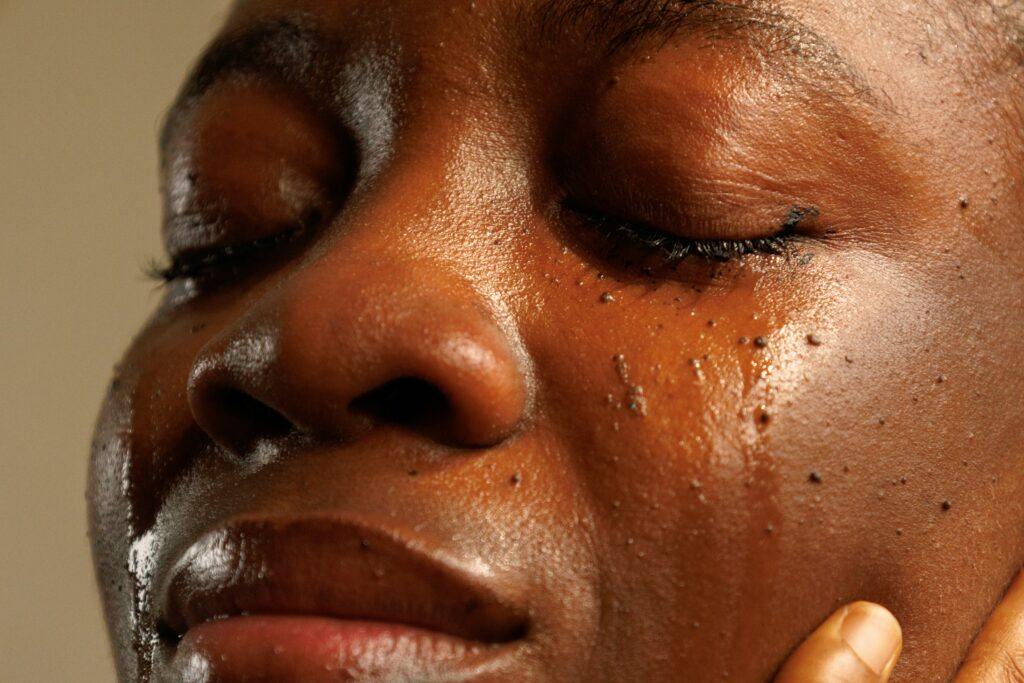

Illustration by Catherine Weir

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Juliana da Penha is a Brazilian journalist based in Scotland. She is the Founding Editor and Director at Migrant Women Press.

Karin Goodwin is a co-editor and journalist for the Ferret, Scotland’s only investigative media coop and co-founder of Glasgow’s Community Newsroom.