Gender-based violence has always been an issue of discussion in South Asian countries. However, in recent years, the number of GBV cases has risen alarmingly. In This Cross-border Collaboration, Indian journalist Nikita Jain and Pakistan-based journalist Rabia Mushtaq look at the parallels of GBV and how laws have failed to protect women or improve their condition with time.

Written by Rabia Mushtaq and Nikita Jain

It has been four years, but for Ifrah* life has never been the same. Belonging to Indian-Administered Kashmir, Ifrah was raped and human trafficked in 2020.

A medical student at the time, who was at her hostel due to COVID-19 restrictions, was approached by Nadeem Nadu, who claimed to be a journalist. He assured her that he was helping people stuck like her to reach home.

Ifrah was picked up from her hostel, drugged and raped by Nadu and his associate, who also filmed her. “When I woke up, they were laughing and told me if I tell anyone, they will release the video,” she told Migrant Women Press.

Ifrah did not tell anyone about the incident due to fear of humiliation and Kashmiri society’s conservative environment. She had to quietly comply. The accused then started blackmailing her. “They told me to go and meet some men. When I refused, they threatened me with the video,” she added.

Ifrah was human trafficked, and she was forced to meet a man. They threatened if she refused to comply, they would release her video. She said that when the man started touching her, she had a breakdown on the spot, forcing him to stop. “He started getting angry and called Nadu, telling him why he sent someone inexperienced,” she said slowly.

It was not until a few months later that Ifrah came to know about a friend who was also their victim and had gone through a similar fate. “She later died by suicide,” she added.

In 2022, Ifrah decided to file a complaint at a local police station. Since then, a long battle for justice has been ongoing.

According to news reports, Nadu and others were arrested on September 30 2022. In her complaint, Ifrah said that the accused took her objectionable pictures after sedating her and used these to blackmail her into forced sexual intercourse many times.

The victim and her family have also alleged that the cases are not being deliberately heard. “The accused in the matter is very powerful. This is majorly why the case is not being heard,” Ifrah added.

The recent National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data revealed there was a 4% surge in crimes against women in India throughout 2022. This includes cases of cruelty by husbands and relatives, abductions, assaults, and rapes.

The NCRB report detailed a substantial escalation in reported crimes against women, soaring from 3,71,503 cases in 2020 to 4,45,256 cases in 2022. Compared to 2021’s 4,28,278 cases, the 2022 statistics marked a troubling increase.

Activist and founder of the NGO ANHAD, Shabnam Hashmi, said that the current political scenario is one of the major reasons India is witnessing a current increase in such incidents.

“What is happening is connected with the overall political atmosphere of the country. It is because violence has increased manifold. People are also realising that they can get away with whatever they do because the state is not taking any action,” she said.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, Rafia Bibi had wished for nothing but a peaceful life after she was married off as a teenager. Like most women in Pakistan, she lived a life dreaming of living a happy married life.

However, some years into the arranged marriage, Rafia’s ex-husband started beating her. She, however, continued to tolerate the physical violence for the sake of her children and to keep her marriage intact. It wasn’t until after her ex-husband married another woman four years ago that Rafia began contemplating her decision to live in an abusive marriage and pursue divorce two years later.

“He started getting hyper. He would beat me up earlier, too, but the violence increased after the second marriage,” Rafia said, speaking about her ordeal in an interview with Migrant Women Press.

For Rafia, it was not an easy decision. She realised it was not possible to live with such a violent man any longer. This happened after she began attending community meetings organised by Women in Struggle for Empowerment (WISE) in her neighbourhood, where women received awareness sessions about their marital and human rights enshrined in Pakistan’s Constitution and law.

“I asked them to get my issue resolved. They first encouraged me to try and resolve the matter with my ex-husband, but when I told them it wasn’t going to work, they helped me in the process,” she said, adding that it was the awareness she received which made it possible for her to take the major step in her life.

In Pakistan, divorce is looked down upon, and women are asked to keep mum about their tumultuous marital life with advice to remain tolerant towards their abusive spouse. The same can be seen in India as well.

Among the total estimated Pakistani population of 241.49 million, as per the latest digital census, the country’s divorced population accounted for 0.35%. The Pakistani society is not kind to divorced women, as the act of leaving one’s spouse is considered too bold, wherein a woman’s moral character is questioned.

But Rafia’s decision reflects her courage. Her family and four children extended their support, knowing how difficult it was for the 36-year-old to continue being married to a man who not only wedded another woman but also inflicted violence.

Rafia also detailed how her ex-husband tried to take away their 16-year-old daughter so that he could marry her off. “I received a lot of help from WISE in this matter, too. We brought my daughter back home. I have spent a very difficult time with that man.”

Bushra Khaliq — the executive director of WISE, the organisation that supported Rafia — told Migrant Women Press that her organisation works to engage and raise awareness among communities at the grassroots level to empower women in four Punjab districts, including Lahore. “In the last one or one-and-a-half month, we received 21 cases, out of which four were about inheritance and 17 were related to domestic violence.”

The story of Rafia and many women like her who choose divorce as an escape from their abusive marriage is an exception. Many women in Pakistan continue to live in such unions while being subjected to violence.

Gender-Based Violence: a major issue in South Asian countries

Both India and Pakistan are conservative and patriarchal societies where violence against women is not only common but also ignored. While there are laws, there is no proper implementation.

With time, the situation might have changed a bit, but for many women the situation remains the same.

While gender-based violence is a global issue, a report by the World Bank has stated that in South Asia, specifically, the prevalence of lifetime intimate partner violence is 35% higher than the global average.

The reasons are complex and include a combination of socio-economic structures, patriarchal attitudes, and prevalent social norms that define gender roles, the report stated.

South Asia includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. While all the countries have major internal conflicts, there are also tense diplomatic relations between them, especially among India and Pakistan governments. But what differs them in religious and political aspects is they make it up on social and gender issues.

Mahnaz Rahman, a Pakistan-based senior women’s rights activist, highlighted that both countries have more or less similar gender-based issues. Speaking to Migrant Women Press, she said, “Both the countries share a lot of common attributes however they have massive religious differences. You see those social and cultural differences, slight maybe, but there are. But this is the only dissimilarity they have.”

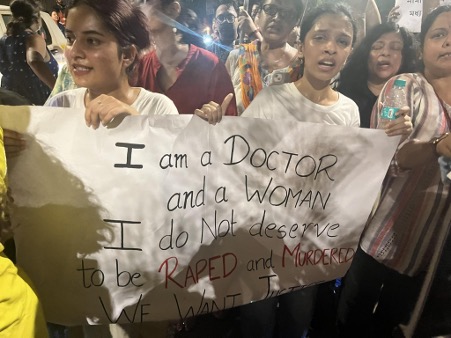

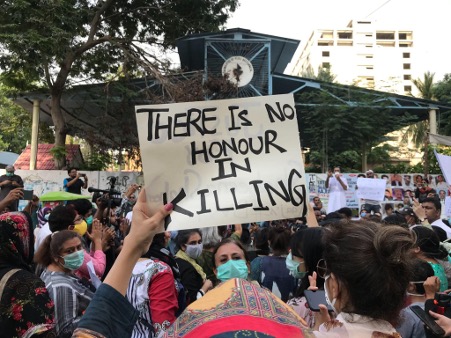

From domestic violence to honour killing (a traditional form of murder in which a person is killed by or at the behest of members of their family due to culturally sanctioned beliefs that such homicides are necessary as retribution for the perceived dishonouring of the family) for India and Pakistan, such issues are a common entity, due to which women are, many times, left to suffer.

Seema Gupta*, 38, married her high school sweetheart at 18. Educated with a degree in German language, she was travelling the world along with her husband. On social media and in public, their life was perfect. But behind closed doors, Gupta had been physically and verbally abused by her husband.

“He used to beat me over every little issue. If I said anything back, it only meant more abuse,” she said, crying.

With two children, Gupta is still forced to live with her husband. With no support from her parents, her life is nothing but a struggle. “If there was support, maybe I would have the strength to leave this abusive marriage,” she added.

Gupta said that there are days when she has been beaten in front of her neighbours, who silently watched. When she asked for help from her mother, she was asked to stay put and tolerate the abuse for the “sake of their children and marriage”.

“There are times when I look at myself in the mirror, my face is swollen, and I feel pure disgust with myself,” she said.

According to a report by BMC Women’s Health, in South Asian countries, the prevalence of lifetime and current physical and/or sexual partner violence was highest in India, followed by Pakistan and Nepal.

No proper implementation of the law

In India, the country made a huge announcement of implementing three new criminal laws: the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam on 1 July 2024.

While the nationalist ruling party — Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — supporters applauded the new move, academics and activists raised concerns over the power these laws gave to the state. They have also been called anti-feminist by scholars.

However, the NCRB data shows a reality that will be difficult to change with such dwindling laws. The majority of cases under crime against women were registered under ‘Cruelty by Husband or His Relatives’ (31.8%). This was followed by ‘Assault on Women with Intent to Outrage her Modesty’ (20.8%), ‘Kidnapping and Abduction of Women’ (17.6 per cent), and ‘Rape’ (7.4%).

Activist Shabnam Hashmi said that women are more reluctant to approach the police due to unsupportive behaviour and victim shaming along with long and tiring legal processes. Speaking about the on-ground situation, she said, “If a woman goes on her own, then nobody listens to her. A complaint is filed only after pressure is created,” she said.

According to Hashmi, it is worse for women who are not educated. “Only when an activist or someone educated intervenes does the police listen,” Hashmi added.

Many activists told Migrant Women Press that when a victim, especially of domestic violence, goes to the police station, they are not taken seriously and, in many cases, offered mediation.

Across India’s police stations, the Crime Against Women (CAW) cell is tasked with handling mediation. If a case is found to fail under appropriate sections, it may be registered. However, many victims allege that during mediation, pressure is created to not go ahead with the case.

More than 18 women die every day in violence connected with the practice of seeking or giving dowry, outlawed more than six decades ago.

Meanwhile, commenting on the Pakistani government’s measures to protect women and gender minorities in the country, Rabiya Javeri Agha, the chairperson of the National Commission of Human Rights, said it is not easy to do the job that all of us are doing and “we are working hard”.

“The status of women is extremely critical and vulnerable. The level of intolerance against women has risen. If you see our report the numbers are all there,” she said when speaking with Migrant Women Press.

According to Islamabad’s Second Periodic Report on Compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights submitted to the UN, the Commission has processed 7,908 complaints, including 1,271 suo motu actions. Around 3,500 cases among the total complaints were related to GBV, women’s rights, and marital disputes.

“The commission ensured proper police registration of GBV cases, provided pro bono legal aid in 1,200 instances, and referred numerous victims to shelters,” the report read.

Uzma Noorani, a woman’s rights activist and founder trustee of the Panah Shelter Home based in Karachi, the country’s largest city, while sharing her views on the state of GBV in Pakistan blamed the lack of implementation of laws for the rise in number of cases as well as the lack of awareness among the people regarding these laws.

“People don’t have awareness. A common woman who remains affected and subjected to domestic violence doesn’t know about the law. Not that the issue is class-based, but poor women are more vulnerable, and many of them keep tolerating violence for a long period of time,” she said, adding that there are economic reasons that force the women into staying in abusive relationships.

Javeri, meanwhile, said that the space for women is becoming exceedingly limited in the country, especially in public spaces including the workplace, parks and markets. “The space for women is being extremely contracted. This is something that the government aims to look into very seriously.”

Pakistan — despite having stringent laws to address the various types of gender-based violence, including domestic violence, rape and workplace harassment — continues to witness cases of abuse inflicted upon women as well as members of the LGBTQI+ community, 90% of whom endure physical or sexual abuse.

In Pakistan, the Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan, which functions under the Supreme Court of Pakistan, underscored the province-wise details of cases overseen by the GBV courts across the country in its 2023 report.

With a total of 480 courts assigned to settle GBV cases, the total number of applications decided stood at 30,631, while 39,655 remain pending. Sexual violence, as per the report, remains the most pressing grave concern, with challenges in resolution ongoing.

The report also highlighted the rise in the number of gender-based killings while including honour killing and murder of women as one of the most alarming issues that continues to make headlines all year round.

In Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest province, also largely composed of tribal communities with their own unique dynamics, a women’s rights activist, Saima Jawad, said that the lack of mobility for women in the region plays a role in them being subjected to GBV as there is no access to resources and lack of awareness.

“If there is no mobility, then women and adolescents have no access to the resources and opportunities,” she said, highlighting that Balochistan has witnessed GBV, including cases of domestic violence, early age and forced marriages and honour killing, while trafficking of women on the border districts was also reported some time ago.

“The districts in Balochistan are far-flung and low in population, which is why the facilities there are not good. Women face a lot of issues in accessing services,” she said, adding that the helpline for women in rural regions is not useful as they do not have access to mobile phones in most cases.

Saima Munir — the KP focal person of Aurat Foundation, an organisation working for women’s rights in Pakistan — said the situation in the country’s northwestern province is no different.

Detailing the sensitivities of the province’s conservative culture, Munir revealed that the cases of honour killing were presented as suicides during its reporting with the police. This also reflects a spike in the number of suicide cases subsequently, while rape cases also remain rarely reported.

“In the past, when Aurat Foundation investigated why the cases of suicides are so high in certain parts of the province, we found out that these were, in fact, cases of honour killing. The station house officer is found favouring the perpetrators in such cases,” she added.

While both countries are busy fighting their struggling economies, the tense political environment and a curb on media voices, issues of gender-based violence are often ignored. However, if we look at cases and data, the situation on the ground concerns where women and their families suffer the most.

*Names were changed on request.

Nikita Jain is a journalist based in Delhi, India. She covers gender, human rights, conflict, migration, the environment, and land rights, among other issues from the region.

Rabia Mushtaq is a journalist based in Karachi, Pakistan. She reports on human rights, gender justice, social justice, migration and culture.