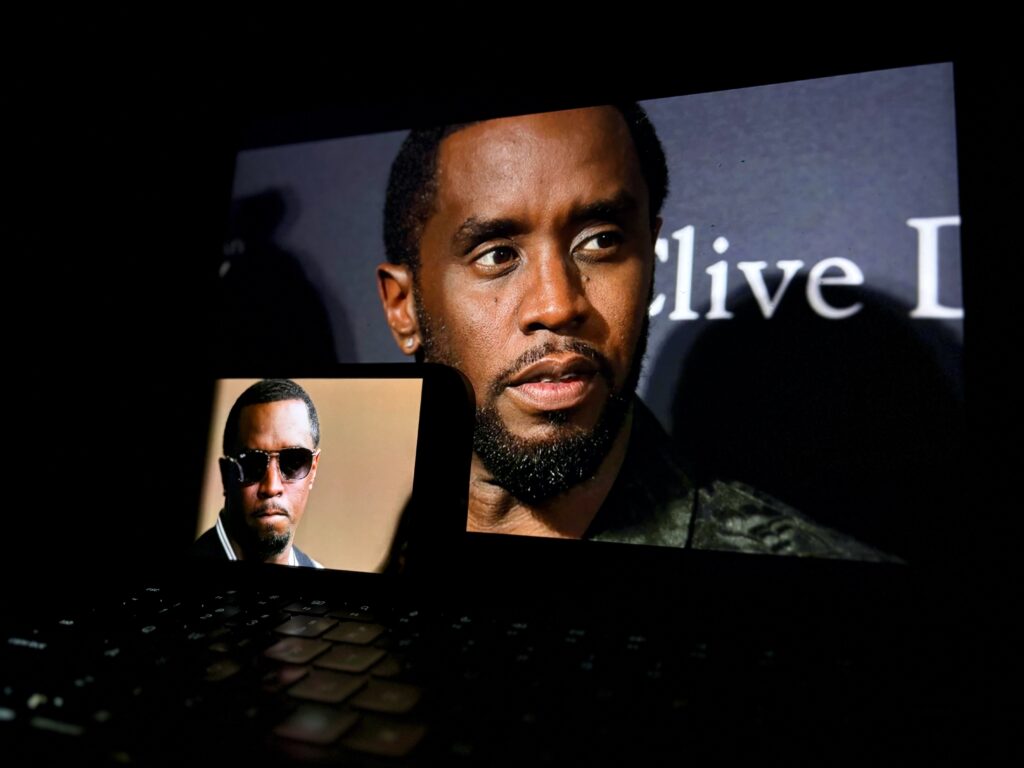

The Online Reaction To Accusations Against Sean “Diddy” Combs And Other High-Profile Men Shows The Public Can Be Enablers Of Abuse, But At What Cost To Victim-Survivors?

Written by Jamila Pereira

Edited by Vicky Gayle

Within hours of the news breaking about US music mogul and rapper Sean “Diddy” Combs’ arrest in September, ahead of being charged with sex trafficking, racketeering and transportation to engage in prostitution, social media pulsed with reactions. “Grab the popcorn, Johnny Depp ain’t got nothing on this,” one tweet proclaimed with laughing emojis, highlighting the similar media circus surrounding Depp’s defamation trial against his ex-wife Amber Heard after she accused him of domestic abuse. Meanwhile, another X user chimed in: “Diddy is not locked up in there with them inmates, them inmates are locked up in there with Diddy”. This wasn’t just a comment here or a post there; it was an avalanche, a theatre of jabs and jeers that turned abuse allegations, dating back to at least 2008, into a trending topic.

Once a space for latte photos and holiday snapshots, social media now hosts a much darker show, where accusations of abuse against high-profile figures play out for likes and laughs rather than reflection. As sexual violence allegations pour from every corner of celebrity culture — from comedian Russell Brand and ex-BBC News presenter Huw Edwards to YouTuber Yung Filly — posts which could call for empathy or change instead spin into a viral spectacle. From TikTok to Instagram, violence becoming viral comedy has been normalised within pop culture, which only serves to enable and exacerbate the toxic language surrounding abuse.

The latest trend of punchlines and controversial theories surrounding Combs’ legal troubles began with a shocking lawsuit filed last November by his former partner, singer Casandra Ventura, known as Cassie. The damning lawsuit accused Combs of rape and sex trafficking, which he denied, and revealed a relationship marked by a “cycle of abuse”.

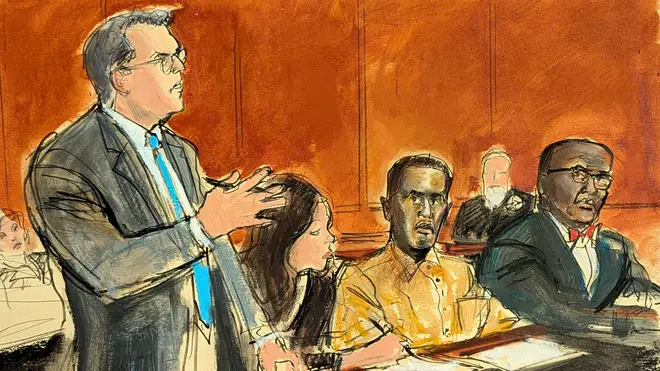

Following the lawsuit, which was settled a day after being filed for an undisclosed sum, many others ensued, echoing her accusations concerning Combs’ long-standing pattern of sexually deviant behaviour. This behaviour had been discussed since the late 90s by the likes of US broadcaster Wendy Williams, Aubrey Oday, a member of Combs’ former girl group Danity Kane, and even by himself in a 2002 interview with NBC’s Late Night with Conan O’Brien. Despite the many public allegations, Combs only began to face justice in 2023 once Ms Ventura’s lawsuit came to light. He is now in custody in New York, awaiting his criminal trial as civil lawsuits pile up against him. There are more than 100 alleged victims so far: women, men and children.

Legal experts have noted that detailed accounts from Ms Ventura and others and the Adult Survivors Act — a New York law that created a temporary one-year window for adult sexual abuse victims to file lawsuits that otherwise would have been too old to bring— were crucial for her case. They also argued that the volume and nature of allegations make it challenging to defend such accusations because consistent testimonies across multiple cases strengthen the credibility of each claim.

Prosecutors also built the case against Combs under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act, known as RICO, which was typically focused on drug barons and mobsters. But “since the start of the #MeToo movement, federal prosecutors in New York have begun turning RICO toward another target: powerful men who allegedly create such criminal enterprises around mass-scale sexual abuse,” law firm partner Cruz Melendez told Billboard. The case is being compared to others involving prominent figures, including music artist R. Kelly and former film producer Harvey Weinstein, suggesting that accumulated evidence from multiple sources may build a domino effect in favour of the plaintiffs, even if the defence counters with claims of consent or disputes the allegations.

Despite the gravity of claims against Combs, as well as the release of distressing footage of him assaulting Ms Ventura in 2016, the accusations of sexual misconduct and violence were widely treated as clickbait. Daunting and uninformed online commentary is not hard to find. One Instagram user wrote: ”Diddy and R. Kelly finna make the jail album of the year” — referring to the former R&B star imprisoned for racketeering, sex trafficking, producing child pornography and child sex abuse. Other users stated: “Keep playing and he’ll be in y’all dreams with a smile and two hand scoops of Diddy oil”, making light of the FBI seizing more than 1,000 bottles of baby oil and lubricant from Combs’ homes, allegedly used during parties he hosted.

Meaningful conversations for the public to engage in about consent, victim-blaming, gender-based violence — and how the pervasive nature of “open secrets” in the music industry enable abusers — have been overshadowed by conspiracy theories, dismissive memes, and troubling misogynistic and homophobic headlines. Charities and advocacy groups addressing sexual violence have also condemned this worrying trend, emphasising the need to centre the voices of survivors to avoid minimising their experiences.

Something equally troubling about Combs’ case is the language being used across social media. Terms like “No Diddy” or “The Diddler” have been rife, and they trivialise the gravity of gender-based violence. They invoke cartoonish images of perpetrators and mask real suffering in sensationalism. Again, this language veils harm behind laughter, casting shadows where light is desperately needed.

Homophobic stereotypes have also continued to frame discussions around Combs’ alleged male victims, of which there are reportedly at least 60. And we ought to shed some light on the prevailing homophobia when many discuss male-on-male sexual assault and how the experiences of men are often overlooked. By refusing to call these assaults rape and assuming consensuality, we downplay men’s vulnerability to abuse, especially in the entertainment industry. Such framing overlooks both the complexity of sexual violence and the systemic culture that makes male survivors invisible while shielding perpetrators behind misconceptions about masculinity. By ignoring these biases, we sideline critical calls for justice and accountability.

As Combs’ case unfolds, it is crucial to redirect focus towards accountability and healing rather than allowing the discourse to be hijacked by unsubstantiated theories and derogatory headlines.

One In Three Women

Almost one in three women worldwide has experienced physical or sexual violence at least once during their lives, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that in the year ending March 2022, about 7.9 million adults aged 16 and over had experienced sexual assault (including attempts). Women were disproportionately affected. Such figures raise a critical question: how can we, as a society, trivialise these experiences through dismissive humour, thereby perpetuating a dangerous culture of normalcy around violence and abuse?

Charities like Refuge and Rape Crisis UK emphasise the importance of education and prevention strategies to challenge damaging societal attitudes and empower victims. Professor Charlotte Watts, an international expert on gender-based violence, argued that data is important for both the prevention of and response to “high levels of violence” occurring online. By amplifying survivors’ voices and supporting data-driven interventions, perhaps we can start to dismantle the insidious culture surrounding sexual violence and foster a more compassionate society.

There was arguably little compassion for victim-survivors in the lead-up to R. Kelly’s trial for sex crimes in 2023. Instead of the focus being on the interventions needed for people to feel empowered to call out predators like R. Kelly, his emotional outbursts during interviews discussing accusations against him, particularly one with CBS This Morning’s’ Gayle King in 2019, took over social media. GIFs were made, often with sarcastic or mocking captions, and social media users even reenacted interview scenes.

These reenactments were set to comedic music or exaggerated gestures, framing profound moments as humorous and blurring the lines between criminal proceedings and entertainment. Treating those serious accusations as comedy and gossip weakened the possibility of cultural debates about accountability and disregarded survivors’ trauma.

For the sake of trending topics, shares and likes, survivors are met with stigma, digital harassment, abuse, persecution and mockery, while their experiences are belittled and sensationalised.

Take the breakdown of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s marriage. Disparaging comments flooded our timelines, mocking her co-parenting and experiences with Kanye and casting her in the trope of a woman undeserving of empathy. Kardashian’s struggles post-divorce were repackaged as memes with each share and retweet reinforcing a narrative that trivialised her autonomy and dignity. Meanwhile, Kanye’s behaviour, which involved harassing and “love-bombing” Kim, was deemed as entertainment by social media users instead of being flagged as emotional abuse.

Then there’s rapper Megan Thee Stallion, who, after being shot in the foot by fellow musician Tory Lanez in 2020, initially struggled to gain public support. Swathes of the public called her a “liar”, and memes branded her “untrustworthy”. Lanez was later sentenced to 10 years in prison for shooting Megan after being found guilty of three gun-related charges in August 2023.

For women facing abuse, such prominent cases being met with ridicule only deepen the perception that their voices will be dismissed or, worse, weaponised. This culture of instant commentary, where empathy yields to engagement, is symptomatic of a digital world where misogyny and apathy are often masked by the language of entertainment and ‘likes’.

Words Matter

The online reaction to Combs and others’ legal issues has shown us that we, too, can be enablers of abuse, even if we are not physically complicit.

The online observations have been, to a fault, immature, irresponsible, graphic, homophobic and misogynistic. Words matter; they echo in the minds of victims and shape how society perceives both the accused and the accusers. Like many scenarios online, the violent and repulsive nature of Combs’ charges has been sidelined by the need to shove shock and clicks down our throats. The deeper we dig into the social media approach to this case, the more distressing it becomes, revealing how far we’ve strayed from addressing the true heart of the matter: decades of alleged abuse.

In the complex landscape of social media, the experiences of survivors of gender-based violence unfold in a dual narrative, one that can both empower and silence. These digital platforms often become lifelines for those who have suffered, allowing them to share their stories and find solace in the solidarity of others. Social movements like #MeToo have ignited a powerful wave of courage that has helped to break the chains of silence and challenge deep-rooted societal norms which enable violence. Yet, this same space can morph into a battleground where victim-blaming, harassment, and trolling thrive, casting shadows over brave voices seeking to be heard.

Survivors may find themselves navigating a minefield of negative commentary that can intensify feelings of isolation and shame and reinforce the stigma that binds them in silence. The very act of speaking out, a crucial step toward healing and justice, can feel risky when the fear of backlash looms large. Thus, while social media has the potential to elevate and validate experiences, it simultaneously poses significant challenges that can hinder survivors from pursuing the support and justice they deserve.

The Diddy case reveals a disturbing reflection of how social media handles violence against women, especially when intertwined with fame and power. Rather than sparking meaningful dialogue or amplifying the voices of survivors online, these stories are often reduced to viral moments — another form of entertainment in a world that is quick to consume but slow to confront systemic harm. The deeper layers of oppression and exploitation get lost in the noise, which drowns out the urgent need for justice and accountability.

As a Black woman, I understand the need to use humour as a survival tool, especially after centuries of systemic oppression. Still, there is something deeply tragic about how society continues to process trauma, both individually and collectively, through jokes and laughter.

Until we acknowledge that no true empathy or healing can come from this, we will remain trapped in this cycle: laughing not just to cover the pain but to keep from truly feeling it.

When supposed jokes push and normalise harmful notions, we ought to point it out. They amplify harm and expose survivors to a new layer of persecution — one that seeps into the real world. The notion of “harmless banter” communicates society’s attitude and tolerance towards sexual assault, especially when it involves famous men. Hence, an ultimate reexamination within the digital world is required so that respect and dignity can be truly promoted.

In this fragile balance, the conversation about gender-based violence must evolve in order to foster a culture of empathy and understanding that encourages survivors to reclaim their narratives without fear. We must sit with our discomfort and carefully unwrap conversations to collectively work toward solutions and truthful change.

Feature image by Steve Granitz WireImage

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger or in need of urgent protection, call the police on 999.

For more info on where to find help, click here.

Jamila Pereira is a Bissau-Guinean culture journalist, writer, poet and International Relations graduate based in Leeds. Jamila’s work can be avidly found both in Portuguese and English through platforms such as Black Ballad, The Republic, BANTUMEN, Open Democracy and more, where she explores cultural shifts and politics of the identity of Black women in the diaspora and beyond. She is also a specialist on migration and GBV, a shortlisted member of the Top 20 Merky Books Writer’s Camp 2019 and a co-author of three anti-racist and political anthologies published by Brazilian publisher Editora Urutau.