Migrant Women Press spoke with three women about their experiences with the Russia-Ukraine war.

by Juliana da Penha

Image credit: Tetiana Shyshkina @Unsplash

When men declare war and go off into battle, it’s always women who are forced into their horrific conflict, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine proves once again.

Since February 2022, the war has created nearly eight million refugees in Europe (UNHCR) and almost six million internally displaced people. 90% of these refugees are women, children, and the elderly.

Ukrainian women have been separated from their husbands and family members. Now they are single heads of households with all the responsibility for their children.

Worse still for these Ukrainian women is gender-based violence. 1 in 5 refugees or displaced women is estimated to have experienced sexual violence. During this war, reports denounced how Russian soldiers weaponised rape and revealed daily accounts of sexual violence against Ukrainian women, including children.”

Three women, three experiences of the war.

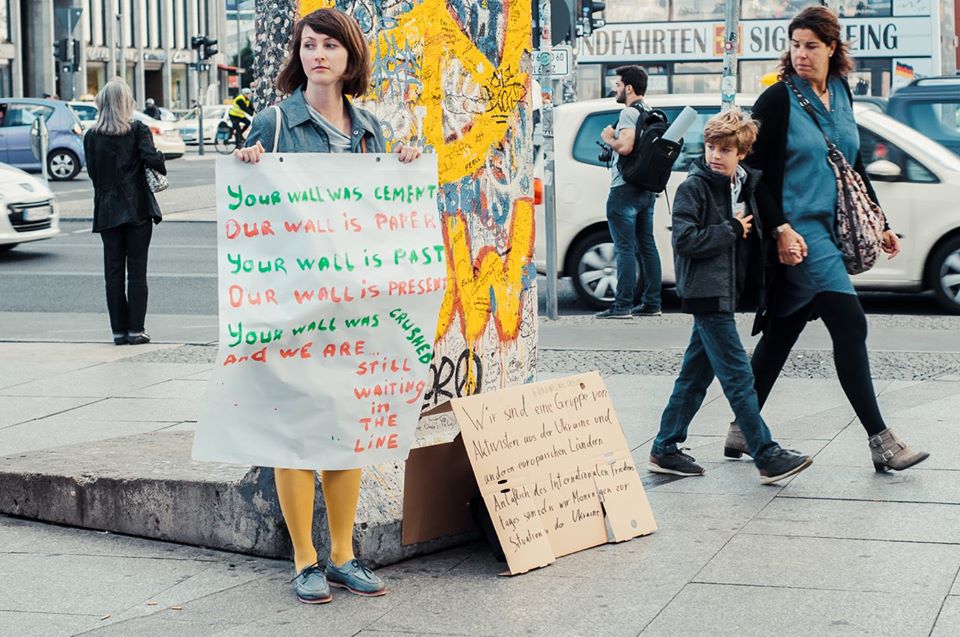

Amid the cruelties of the Russian-Ukraine war, there is resistance and collective support by women on the frontlines and abroad.

When the war started, Clara Magalhães, a Brazilian living in Germany, travelled to the Ukraine and Poland border to volunteer to rescue people from conflict zones with her car. She has continued this work until today.

Yulia Lashchuk, an Ukranian interdisciplinary researcher about Ukraine female migration living in Italy, was in Ukraine visiting her parents and woke up at 5 am to the noise of explosions. She left Ukraine on foot with hundreds of women and children, now all refugees.

Lili T., a Slovakian IT professional in the Scottish public sector, was in Spain on a surfing trip that had barely started when she heard the news. She went to Hungary to help Ukrainian refugees as an interpreter.

3 migrant women from 3 different countries share their experiences with the war.

“We have this frustration feeling at this moment as things have this “normality level”, Clara Magalhães, Frente Brazucra

“…the war goes on. People continue to die. Cities continue to be destroyed. Lives continue to be shattered. Do not forget.”, Clara pleads in a Frente Brazucra Instagram post. After four months of the ongoing conflict, she draws attention to the fact that, as other issues become daily news, people’s attention to the Russian-Ukraine war declines.

This normalisation of war also impacts humanitarian work: “It becomes more difficult to collect donations, to help and even to work as a volunteer.”

Frentre Brazucra is a volunteer organisation created by Brazilians amidst the Russian-Ukraine war, aiming to rescue Brazilians from the Ukraine conflict zones, helping them find shelter and basic needs.

When the war started, Clara left Germany, travelled to the Poland-Ukraine border, and, with other volunteers, began to rescue people in their cars and collect donations for refugees.

Since then, Frente BrazUcra has helped hundreds of people in need from different nationalities. They created a crowdfunding campaign to cover the costs of their operations and organise logistics with volunteers and donations from other countries.

Clara explained there are different issues people in Ukraine face because of war. “On the east, you will lack medicine, food and water for civilians and the army. There is a lack of basics for the Ukrainian army, like bulletproof vests and helmets. For the civilians, the food is not arriving, in lots of cities lack water and electricity. We are facing a huge fuel crisis, this has been a commodity here in Ukraine since the beginning of the war, but the situation is getting worse”, explained her.

“…the war goes on. People continue to die. Cities continue to be destroyed. Lives continue to be shattered. Do not forget.”

Clara is helping many people, but I wondered how she managed to protect herself from the negative impacts of the war on her mental health. She believes this work goes beyond what she is seeing and experiencing. It gives her the strength to keep going and overcome many obstacles, including extreme workloads. “One normal basic day lasts 14 to 20 hours.”

She also reveals issues with immigration control on the Poland-Ukraine border. “If you are lucky, you find nice people. Some people already know me. But every time, they change the immigration officers. They are rude; they scream and don’t have the minimal intention of treating you as a human being. Even the police are like that.”

On the other hand, she feels grateful when arriving in Ukraine to help people. When she explained that she was from Brazil and had been helping people since the beginning of the war, their appreciation for her efforts gave everything a sense. On the worst days, she keeps going as she believes it is worthwhile.

“Our work is making a difference, and we are lucky to find people that remind you about this feeling, and you keep facing all the difficulties to work here”.

When the war in Ukraine started, the world looked sympathetic to the Ukrainians and their struggle. But Clara doesn’t believe there is more solidarity in the world. “Some blame the victims. It’s shocking. We see this in different spheres; for example, in femicide and rape crimes, we blame everyone but don’t look at the roots of the problem.”

“It was a weird situation when I was both a researcher about Ukrainian female migration and a refugee myself.” Yulia Lashchuk

“When I woke up from the explosions, I was sure my neighbour was doing some work in the house. It was noisy and loud, but I didn’t want to believe it. And when it was obvious that it had happened, my thought was: “What should I do now?” Yulia explained her first thoughts when the war started.

A migrant woman for more than ten years, now living in Italy, Yulia was visiting her parents in her hometown Lutsk, on the Western side of Ukraine, close to the Polish border. When she realised she was crossing the border by foot with hundreds of women and children.

Yulia is a researcher about Ukrainian female migration and a cultural activist living in Italy. “I am looking for alternative ways to tell their stories. Not only in the scientific papers, in a limiting way, but also to step beyond and use some artistic methods.”

She is the founder of The Museum of Ukrainian female migration, a project that just received a grant to put together all the data she collects. The aim is to create an interactive map where you can see the dynamics of the migration and learn about the history, different ways and the gender dimension of Ukrainian female migration.

When the war started, Yulia’s research side stepped back. “I heard many stories, but I didn’t record anything. I didn’t take any pictures because, at that moment, I felt that we were all on this together.”

A sense of responsibility towards her community but also a feeling of guilt was constantly in her mind. “It was difficult. This feeling of guilt was always present; the guilt for staying alive, going away, being more privileged, and not being able to help everyone needed. I was so exhausted. I wasn’t resting, and I collapsed. One day I just collapsed”.

It was challenging to leave Ukraine when Yulia’s family members were still there. However, now she is the only one in the family working. Her parents lost their jobs because of war, and now she is responsible for caring for them. But she couldn’t do her work from Ukraine “my brain couldn’t work; it’s a constant danger, and you hear the alarms all the time, and you have to go to the shelter all the time. It’s impossible to function normally.”

After the war, she took an additional full-time job in Italy on top of her research projects and volunteer jobs. “Now it’s almost 24 hours of doing stuff. Physically I am exhausted.”

There are also changes in her routine. Check-in on family members constantly since she opens her eyes in the morning until she sleeps. “It’s tough to be an adult here.”

This war is complex and challenging to explain. She thinks the metaphor of a toxic relationship helps to understand the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “When your partner doesn’t want you to leave and makes everything to keep you stay and use physical violence. If you say something like: I want to be part of the European Union. And they say: No! You can’t leave me! You can’t be part of the European Union! You have to stay with me, and you will stay with me!” It’s an aggressive, violent, toxic relationship. We want to stop, but they do everything, so don’t let us go.”

“The situation also made me realise that 100 years of universal suffrage for women, all the progress feminist movements made means nothing in the face of weapons.” Lili T.

“I couldn’t sit (or surf) on a beach while all was happening”, said Lili, who was in Spain when the war started, just starting her surfing trip.

“It felt like being thrown back into a Cold War-era nuclear crisis. Not that I lived through it, but the atmosphere must’ve been similar. I’ve heard stories of Russian soldiers’ behaviour from my family. I didn’t expect them to be very different this time.

She quickly applied as a volunteer for various organisations while she made her way to Central Europe. When she arrived in Budapest, there were stands at the train station with food, clothing, accommodation, and transport offers.

Initially unsure about how to help in the middle of many emergencies, Lili realised she could help as an interpreter as volunteers struggled to communicate with Ukrainian refugees. She said Ukrainians rarely spoke English.

While working as a volunteer interpreter helping Ukrainian refugees in Hungary, Lili recognized many issues they faced: language barriers, challenges to finding long-term accommodation, inability to find qualified work and exploitation by wages below the minimum legal level.

Additionally, fear was a constant theme. “Fear of being in a foreign country, not knowing what to do. Fear in general. Believing the war will be over in a month or very soon,” she explained.

“I asked a woman which country she’d like to go to; she said: ‘I want to go home,” Lili explained the common feelings of homesickness and the fear of loved ones being left behind. “An older lady first accompanied her daughter and grandchild (her son’s son) to safety in Turkey, then wanted to return to Zaporizhzhia to her son and daughter-in-law. They joined the Ukrainian army to fight. She was terrified to even get on a bus, confused, yet she wanted to take the first night train to Ukraine.”

There is a real threat of human trafficking, being taken into slavery or prostitution for refugee women: “Being seen not as refugees, mothers, but as sexual objects, easily obtained because of their vulnerability. Many men are excited about the number of beautiful young women arriving. Men were coming to the station offering accommodation to “women only”, which should light up every red flag-shaped cell in one’s mind”, explained Lili.

She also revealed the issues women who manage to arrive in host countries face. “Not being able to find work while taking care of small children, yet unable to provide for their children from the support received. A mother in northern Italy told me she received 200 EUR a month but struggled to feed the three of them; prices were very high. She has since returned to west Ukraine out of homesickness, as did many others. One lady said she wants to return to her flowers in Odessa; she’s old and not afraid of rockets.”

Working as an interpreter in a humanitarian context is complex; as Lili experienced, “Sometimes I wasn’t fast enough to recognise shock symptoms. I became very impatient with a woman who spoke very fast, couldn’t decide and didn’t accept any offers. I left her in the care of her friend to make up her mind, only to realise she must’ve been in shock – her pupils were wide open and didn’t move at all in the station’s shadows. I returned to her, learnt more about her plans, found suitable accommodation, and hugged goodbye.”

All these experiences brought Lili thrilling lessons. First, it was a surprise for her, always on the quiet side, to end up as an interpreter. “Wanting to help is not enough if you don’t have the skills; at the same time, a lot can be learned while helping. I learnt to be more directive, manage, command and demand, see options faster, and act towards a solution.”

And solutions can present themselves by surprise. “A Swiss couple came to the station, and luckily, someone grabbed me to translate for them. They were travelling back home the next day and were offering to buy flight tickets for refugees, as many as there are places available. That night two families got tickets, and the next day, volunteers found another 2 families”. Altogether 12 people landed in Zurich.

“We are all the same”, replied the Swiss lady to my thank you. I talked about Iraq/Afghanistan with her; she told me she has two Afghan ‘brothers’ in Switzerland. ‘Our’ children have already started kindergarten and school in Switzerland.”

Amidst the suffering conflict always brings, hope still comes from ordinary people’s actions.

* Some names have been changed