“A therapist documenting and co-creating histories of migrant women”, Naila Ali reflects on her personal journey and explores identity, trauma, migration, and displacement. In Migrant Women Histories, she records photographic memories and biographies of migrant women living in London using storytelling and art, as a therapeutic process.

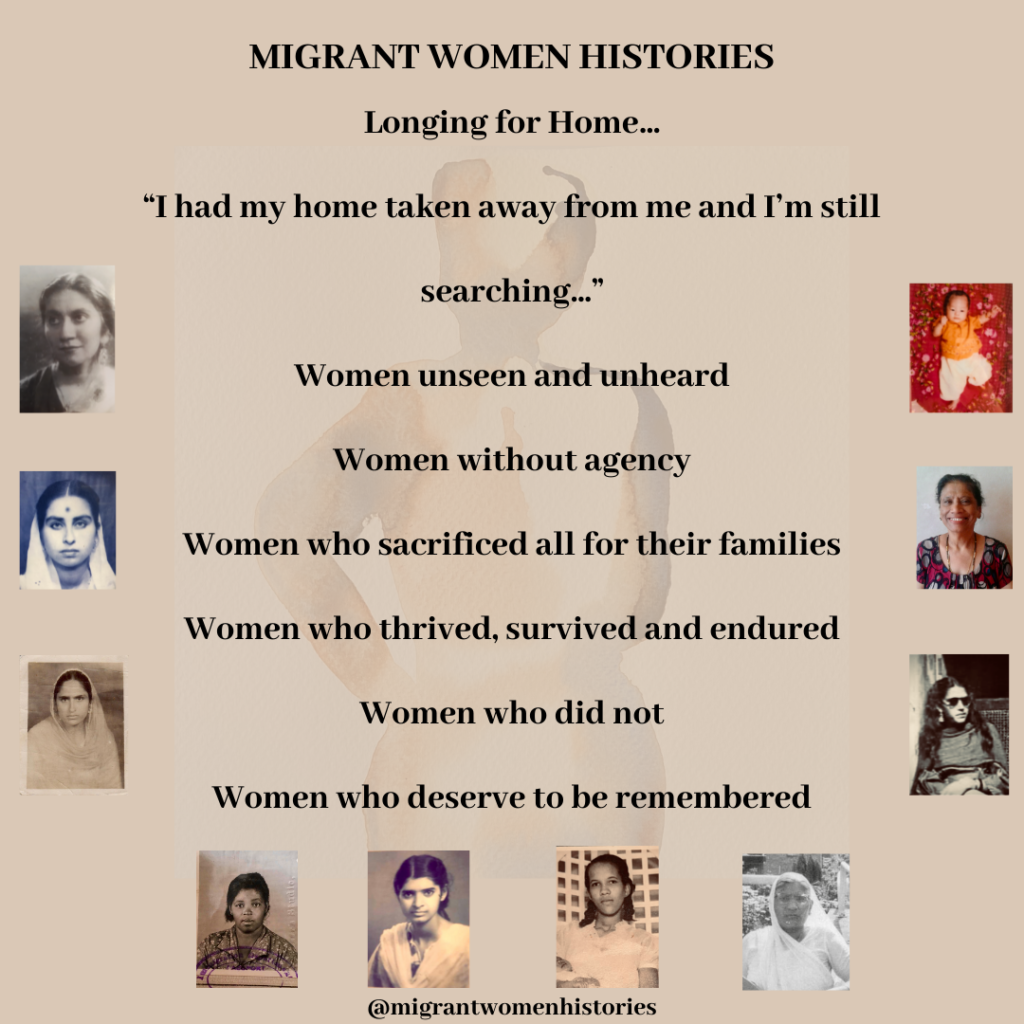

“These humble women, hard working women, made sacrifices, were courageous, strong, resilient, and kept going. Even when lots of people would give up, they kept going.”

by Juliana da Penha/ Image by Etienne Girardet at Unsplash

“For women of colour, it is a constant struggle. Every day, when one goes out into the world, one deals with all the assumptions people make,” reflects Naila about her journey.

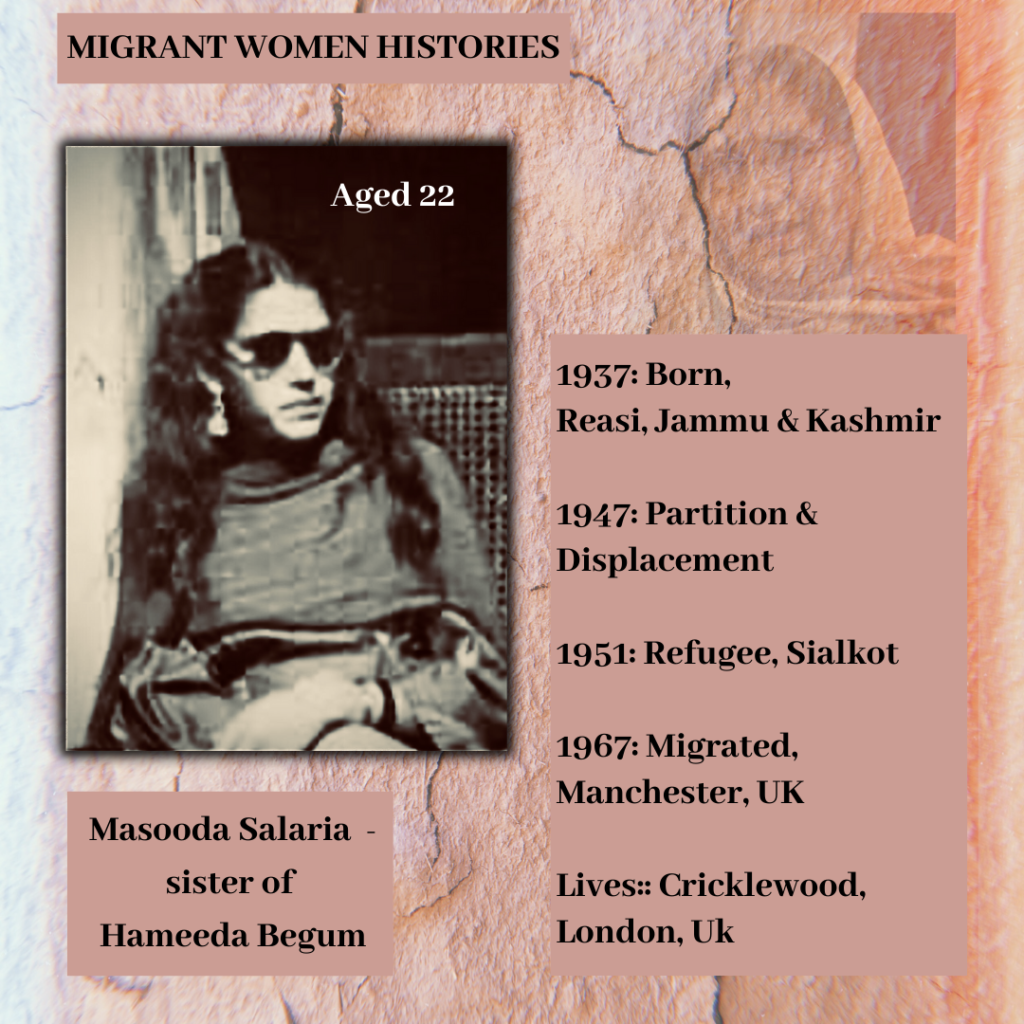

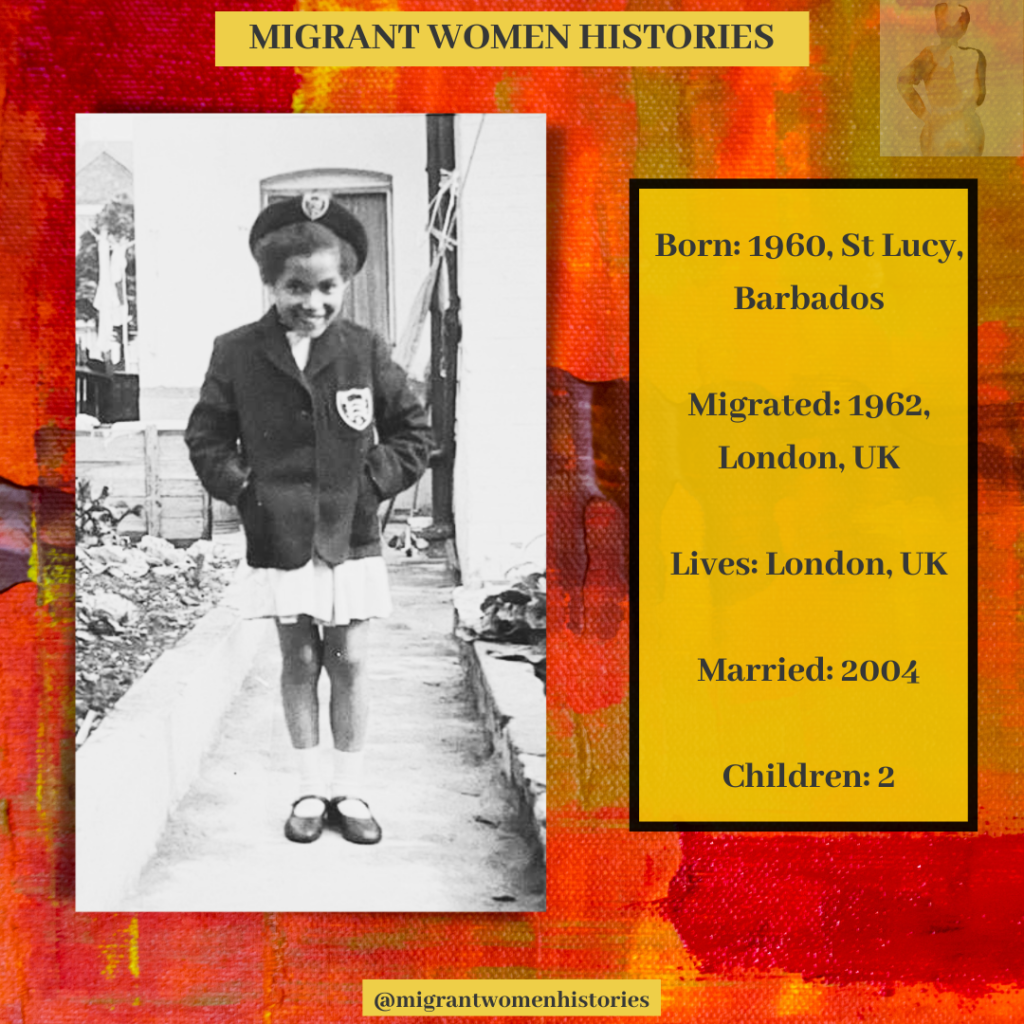

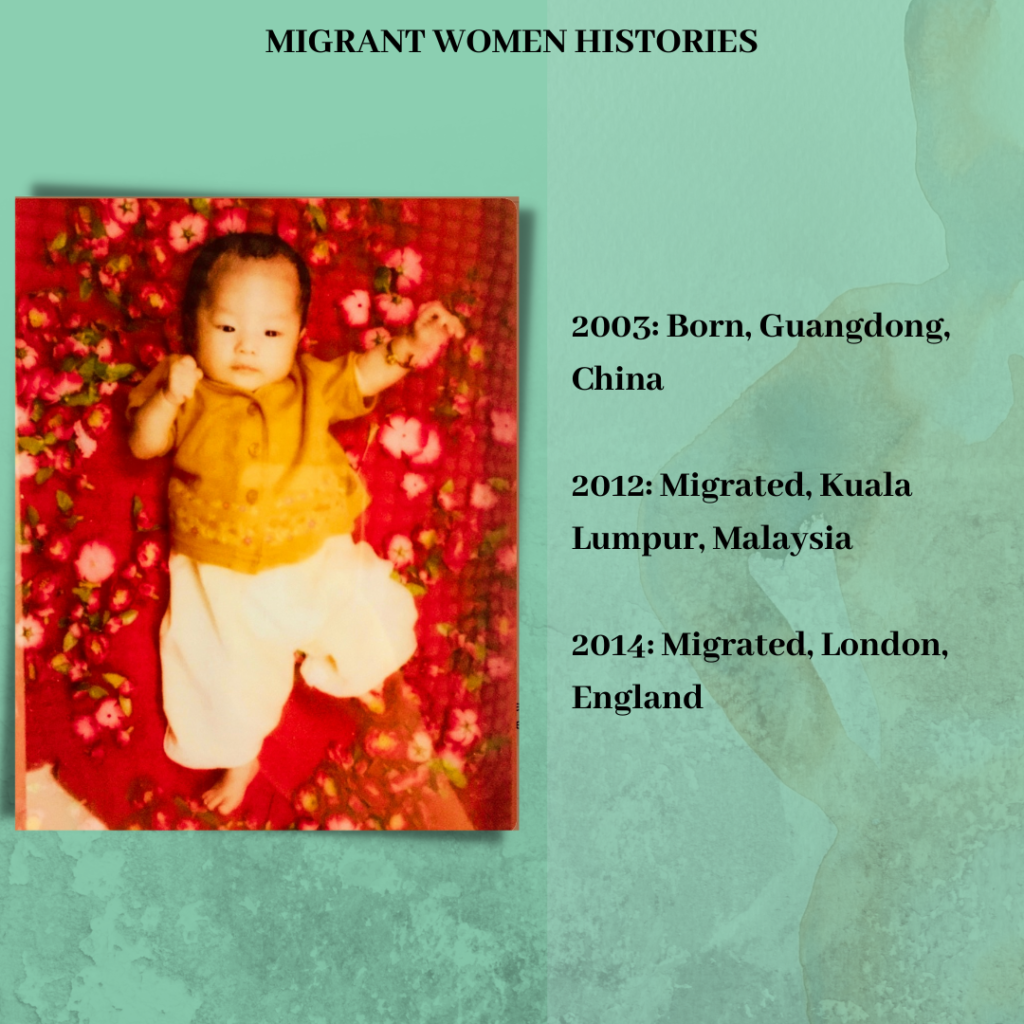

A woman of colour living in London, where she arrived at only 19 months, and a therapist, Naila Ali is the founder of Migrant Women Histories, an archive of narratives and photos of women who migrated by choice or through displacement. Migrant Women Histories echoes all the challenges these women faced and, at the same time, celebrates their achievements.

“I feel we need to create space for their stories, women who have done amazing things and survived lifetimes of challenge and trauma,” says Naila. She believes these stories will disappear if not registered once these women are gone.

“If we don’t document the stories of these women, stories that perhaps only their children, family or friends are privy to and in some circumstances stories that have never been shared with anyone, they will be forgotten. These women need to be remembered.”

Although reluctant to use social media initially, she got advice from the young people around her and realised Instagram could be a starting point to share these stories.

“The stories collected so far are mostly from people I know directly or indirectly. I hope people will contact me via Instagram to share more stories. I have realised that this is not an easy task. I now understand that women may not have reflected on their lives and the challenges and trauma they faced; perhaps there is also shame and stigma”, explains Naila.

“If we don’t document the stories of these women, stories that perhaps only their children, family or friends are privy to and in some circumstances stories that have never been shared with anyone, they will be forgotten. ”

Sharing is healing. Naila discovered that having overcome the barrier of telling their story, these women and family members appreciated the positive impact of storytelling. “Quite often, the women felt their stories were not important, that they hadn’t done anything that deserved recognition. Once they had gone through the process of looking back, they were so grateful that they had been invited to do something they hadn’t even considered. They discovered events they knew nothing of, belongings stored away that they were able to share together. If these conversations hadn’t happened, they might have died, and the opportunity lost forever.” Because this is a collective work, every family who has shared always said thank you for setting them along this path to discover more.

Naila doesn’t want to push women to tell their stories before they are ready, so the process starts when she talks with them about it whenever she makes a connection. She believes when these women are prepared, they will share.

“Once, whilst shopping, a young woman working in the shop, asked me where I was from. She was also a woman of colour, and we began chatting. Depending on who asks this question, I/we receive it in a particular way. We had a wonderful conversation, and I then mentioned the project. She said, “Oh my God, it would be great to tell my mum and her sisters’ stories. I felt it should be shared, but I didn’t know where”. I love it when that happens, and I believe things will happen organically. I just put out an invite, and people respond when they are ready.”

Interview with Naila Ali

What do you learn from the women you interview at Migrant Women Histories?

Naila Ali: I am constantly blown away by interviewing these women and writing these stories. Blown away by the courage, determination, strength, what they went through, what they managed, and what they survived. Women have said: “Why do you want to write a story about me? My life is boring; it’s not important!” I was struck by their humbleness. I suggested they think differently and reflect on what they have done and achieved. These women survived partition, are part of the Windrush generation, faced all sorts of trauma, and yet do not understand they are our living history, part of the fabric of our society.

Could you talk about the therapeutic benefits of sharing personal stories?

NA: I think for everyone, to release the burdens we carry in our bodies physically, is important and necessary; if you can write, write; if you can share, share. I think it is a release; it can be healing. I don’t think there is anything negative in doing so. It can be scary; there might be shame attached but write your story for yourself if you can’t share it with other people, it will be personally beneficial.

Every single woman and family who has shared a story has had a positive experience. They feel seen and heard, recognised for their achievements, for the survival of their story. Their families have been able to do what they did because these women carried those families.

Is there a particular story that touched you differently?

NA: Every story makes me emotional. These humble, hardworking women made sacrifices, were courageous, strong, resilient, and kept going. Even when lots of people would give up, they kept going.”

I feel very privileged when these women share their stories with me. Each story is very precious, and I treat them with respect. There is a magnitude; I hold the story with seriousness and recognise its importance.

“These women survived partition, are part of the Windrush generation and faced all sorts of trauma. And yet do not understand they are our living history, part of the fabric of our society.”

Could you tell me a little about your experience as a migrant woman of colour in England?

NA: Even as a very young child, there was a feeling of being different. Arriving on the first day of school, I didn’t feel different, but I was made to feel different when I left. People who are in places not of their ancestral origin always feel different. They are trying to fit in as much as possible, doing that alongside the other everyday life challenges. It’s a massive extra burden that has to be managed. And if I think about children, I work with children as young as 5; it’s painful to observe how much they are managing daily.

I have siblings who spent years in Pakistan before they came here. I was a baby, so I didn’t have that experience. And there is something that many other people with a migration background have spoken about, the feeling of being different within their own family as well. You feel different in your home, where you should be familiar and comfortable. I used to feel like an outsider.

I always felt in between, never quite in one place or other. It is a constant, never-ending search to find a place where I can put both feet and say this is where I belong. But I haven’t, and I think I have reached the stage where I embrace my experience. I feel content, appreciate and understand that this is what I am, although it can be a lonely place. We have no choice; we must embrace it. But for me, it’s a difficult place to sit; being a brown woman is a constant struggle. Every day when one goes out in the world, there are assumptions people make. And then I speak with an English accent, and there is a perception, “Oh, you speak like us, but you don’t look like us.” And within my community, there has been negativity, “You speak like that! Do you think you are something special?” And people can distance themselves from me. I didn’t understand it as a young person, but now I realise they couldn’t quite place me, “This woman looks like us, but she doesn’t behave like us; she doesn’t speak like us.”

“I always felt in between, never quite in one place or other. It is a constant, never-ending search to find a place where I can put both feet and say this is where I belong. But I haven’t, and I think I have reached the stage where I embrace my experience. I feel content, appreciate and understand that this is what I am, although it can be a lonely place.”

How this feeling of loneliness impacts migrant women’s mental health?

NA: Many women who came over when they were young and married or if they stay very much within their communities and do not take part in the wider community become isolated and lonely. When they first arrive in a country entirely different from their lived experience, I think they are in a survival mode and remain in the familiarity of their own community. On an everyday basis, everything is different, the weather, the culture, the language.

Historically, when women present signs of poor mental health, they are labelled as neurotic rather than being seen and heard, allowing that safe space to express what they are going through.

It would be interesting to compare the mental health state of two groups of women; one from Pakistan that never left the country and another who migrated to the UK in the 60s and 70s and spent 50+ years here.

“Historically, when women present signs of poor mental health, they were labelled as neurotic rather than being seen and heard, allowing that safe space to express what they are going through.”

What are the consequences of racial discrimination on mental health?

NA: It is a broad question and not one that can be easily answered. However, there can be a gradual shutting down of a person, becoming isolated and withdrawn. Psychosomatic illness can occur; we see people with bodily aches and pain. I know many women who have constant headaches and take painkillers regularly. This is the body speaking. There are books and research about the body telling us things about ourselves. There is a lack of awareness regarding such ailments. They are treated as physical issues without recognising the possibility of underlying poor mental health.

If we look at the life cycle of the global majority in this country, the opportunities and pathways that are available are vastly different; this disparity chips away at an individual’s mental health. It is also important to note that each person’s story should be heard as a unique story. It can be a further trauma when someone assumes they understand racial discrimination and understand your account.

What is your advice for women struggling with their mental health?

NA: If women are part of a network of women, maybe the ones they see in the school playground, perhaps family members, I would suggest they start talking with these women about what they hold. Learn to share your struggle with a trusted person. In sharing a problem, the pain is not taken away, but it may be reduced if the burden is shared. The more we talk, the stigma of mental can be reduced. People can support each other by listening and giving advice on where to go for help. As a mother, my advice is to see and hear your children and provide them with space to express their feelings. Sometimes children will find it difficult to express what they are feeling. I would say to anyone, not just parents, sit alongside someone and don’t speak but be with them, so the other person knows you are there. Even if it is for a few minutes, allow that silence to be there and let that person know you are there when they are ready. It is valuable because we live in a hectic world; we never stop. Even before I started my training as a therapist, I noticed that stressed parents would not really ‘be’ with them while managing hectic diaries for their children. I would suggest maybe try to stop for a moment as you give your child a hug or a kiss; really stop. Maybe don’t ask your child, “What did you do at school today?” but rather: “How do you feel today? How was your day”. We all live hectic lives but take at least 5 minutes in a day when you stop and listen.

Find more about Migrant Women Histories at their Instagram page @migrantwomenhistories