Conversation with Soledad Requena, Gender Advisor at CEMIR, Center of Migrant and Refugee Women, in São Paulo, Brazil. International Consultant on Gender and Migration, Soledad tells us a little about her history as a migrant woman and her activism in the areas of gender and migration. She talks about CEMIR’s work and explains the difficult situation of women in Brazil at this complex moment with the pandemic.

✍🏾Juliana da Penha

“Ama qhilla, ama llulla, ama suwa” (don’t be lazy, don’t be a liar, don’t be a thief)

The above proverb, in the Quechua language, is part of the popular wisdom of the Andean peoples (Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador), transmitted since childhood, told us Soledad, a Peruvian and migrant woman, who currently lives in Brazil.

Soledad’s experience with migration began when she was 5 years old after her entire family migrated from the Peruvian countryside to the capital Lima in the 1960s. “I have the scene very clear, we travelled by train, my mother told stories of what our life would be like in this new world. We brought a colourful trunk, where my mother kept pictures, our documents. It was a very remarkable moment for the whole family”.

Soledad never forgot the phrase his mother said when they arrived in Lima “Lima won’t beat us, we’ll beat Lima”. She compared her experience with people from the Northern region of Brazil who migrated to São Paulo in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Soledad’s mother was semi-illiterate, with 11 children but always said that women should study. “Even though she grew up in the countryside, within a different logic, where men were oriented towards study and women towards domestic activities, she encouraged her daughters to study. She totally changed her outlook. She invested a lot in our study”.

Following her mother’s advice and her instinct, Soledad soon became a leader. She was a militant in the high school student movement and one of the founders of the national coordinator of high school students in Peru “I think I already had in my blood the leadership and the feminism very internalized.”

“I think I already had in my blood the leadership and the feminism very internalized.”

In many women experiences, pregnancy and marriage change their direction and personal projects. And with Soledad was the same. After getting pregnant and married, she went to live in Brazil, with her husband family. And there, she got to know a bit of the reality that many migrant women face in a new country “I was different and didn’t speak Portuguese well. I learned to speak Portuguese from the agricultural workers on my father-in-law’s farm. They were my teachers”.

Decided to continue her studies, Soledad concluded a Social Work degree, at the time she was the only foreigner in university. “And there I felt the discrimination because in my time there were no positive actions, no black people, no people from other regions of Brazil, and no people from other social classes.”

One of the strategies that many migrant women use to tackle discrimination and other forms of oppression is to exploit their potential. And with that in mind, alone, with two children, working and studying, she concludes her studies. “Even with all the discrimination I didn’t give up, I never forgot my mother’s phrase.”

After this significant step, she decides to return to Peru so that her children can also live with their culture and family. There she works in organizations like UNICEF, works in European Union projects and stayed there until she felt the “empty nest syndrome” since her two children came back to live in Brazil, in São Paulo.

And when she returns to Brazil, she begins her trajectory in migration work. She recalls that it all started when she was invited to the “March of Immigrants”, an annual event that takes place every first Sunday of December in Sao Paolo, and gathers all nationalities, coming from all over Brazil. “When I went to the march of immigrants, I met my tribe again,” she explains.

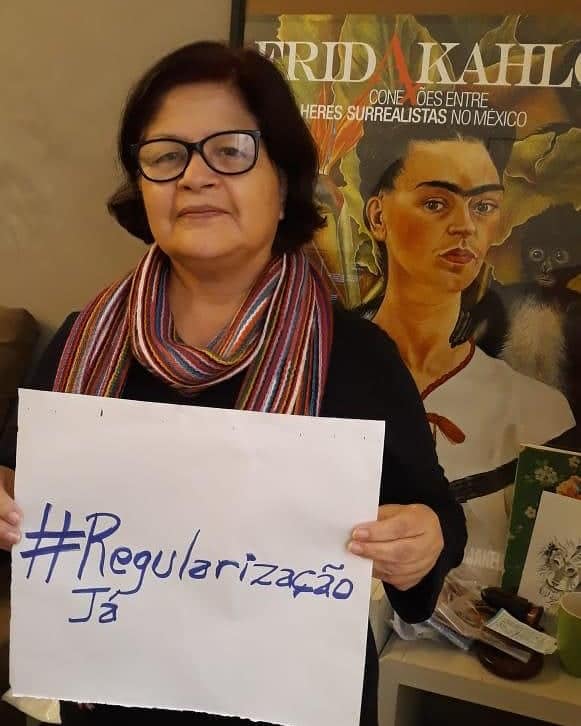

Soledad has made a journey working in organizations and projects related to immigration in Brazil. Today she works at CEMIR, which during the pandemic is developing emergency actions, such as the distribution of essential food packs for women in situations of social vulnerability. Another action, recognizing the increase in the number of cases of domestic violence during quarantine was the creation of the campaign “Quarantine yes, violence against women no”, joining the voices of Brazilian and migrants to denounce violence against women during the pandemic.

“Even with all the discrimination I didn’t give up, I never forgot my mother’s phrase.”

Interview with Soledad Requena

Tell us how you got involved with the issue of migration in São Paulo, especially with migrant women?

Soledad: In São Paulo, there was already a demand to work with immigrants, but there was a lack of a gender perspective. The presence of women became a phenomenon, the feminization of immigration. Today we can say that migration has a woman’s face.

Five years ago, no NGO was working with gender in immigration. So, I started working in an NGO in São Paulo to initiate this work with immigrant women. I begin my contribution incorporating the gender perspective and using Paulo Freire’s methodology, to identify leaders in the neighbourhoods, strengthening bases in each community. Thus, I began my work with immigrant women.

In Brazil, mainly in São Paulo, which is the biggest city, the majority of immigrants are Bolivians. We started this work with Bolivian women who are inserted in the productive chain of the confections, victims of slave-like work, many of them were victims of human trafficking and, besides everything, they suffer domestic violence.

Working with the gender perspective with immigrant women in a non-secular institution makes it challenging to develop essential issues such as sexual and reproductive rights, economic empowerment, among others. To continue to work with migrant women, insisting and resisting with the dream of women’s emancipation, I was invited to work at Center for Immigrant and Refugee Women, CEMIR.

I begin my contribution incorporating the gender perspective and using Paulo Freire’s methodology, to identify leaders in the neighbourhoods, strengthening bases in each community.

How did CEMIR advanced a gender perspective in the work with migration?

Soledad: We started our work as a collective, as a group of women, three years ago. Then we created the NGO, the Center for Immigrant and Refugee Women.

As I explained earlier, we observed that in the last 5 years, there has been a change in the profile of immigration. Women’s immigration has increased a lot in Brazil. We are now talking about immigration with a woman’s face. They come from different countries, but mainly from Bolivia and in the last year many women come from Venezuela.

Many of these women arrive alone with their children. At the beginning of CEMIR’s activities, we had clear that we would work with the migration issue, but soon after we integrated a gender perspective, based on statistics of the growing migration flow of women in Brazil.

Women’s immigration has increased a lot in Brazil. We are now talking about immigration with a woman’s face.

What projects, activities and support does CEMIR offer to migrant and refugee women?

Soledad: We have the “Rodas Warmi ” (women’s circle). In the Quechua language, from the native peoples of Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador, Warmi means woman. We use these circles to bring women together in the neighbourhoods. In the analysis we made we outlined the strategy of going to the peripheral areas, where the immigrants are and where the presence of women is noticeable. We have a network in 13 neighbourhoods, and in each community, we have a leadership that lives in the territory. Our strategy is also using the concept of territory. The woman leaders live there and have a relationship with the women who live in the surroundings. We identified the migrant women leaders, spoke with them, and we make the proposal to carry out this work.

The work of migrant women, mainly Latinas, has a history of collective action. So, for us, it is not difficult to work like this. As I’m Peruvian, I know this reality, I’ve worked with community organizations for a long time, so it’s something natural. The collective culture makes sure that leadership always exist. So, we identify these leaders, and we invite them to do this work in each neighbourhood, bringing women together, because they know each other and dialogue. They invited these groups of women to work within the Warmi circles to talk about empowerment, the rights that they have as women, as human beings. And also, what rights they have in Brazil, according to the Brazilian Immigration Law.

Our other actions are workshops, which we call “Tamos juntos”(We are together) using Arpillaria, as a form of knowledge of rights, of how to identify gender violence, discrimination, xenophobia. The Arpillaria was widely used by indigenous women in Chile at the time of the Pinochet dictatorship, stimulated by Violeta Parra, an artist and artisan. They began to develop this technique with a lot of creativity, at a time of great difficulty in Chile.

Another project we developed is with soccer. Practically the entire community of Latin migrants’ practices soccer, and it is an exciting logic because Bolivian women also practice a lot. Women’s soccer in the context of Latin, Bolivian migration, especially in São Paulo, is tremendous.

The work of migrant women, mainly Latinas, has a history of collective action. So, for us, it is not difficult to work like this. As I’m Peruvian, I know this reality, I’ve worked with community organizations for a long time, so it’s something natural. The collective culture makes sure that leadership always exist.

Can you talk a little more about the Warmi circles? What are the other questions discussed?

Soledad: Most of the women who attend our activities work in sewing factories, where the working conditions are analogous to slavery. Besides being victims of these precarious conditions in the sewing factories, they are also often victims of violence, which can be from a boss, a relative, because often the relatives are the owners of the workshops. And often it is their husbands. In the Warmi circles, we also work on these issues. We also talk about child labour. In the culture of a large part of the population of indigenous origin, the work has a different concept from the legislation. For them, younger you start working, it is better. We work to deconstruct this idea, to guide them, to inform them that these conditions can interfere with the study, in school.

In order not to confront the Andean and indigenous culture, we have a horizontal dialogue. We use Paulo Freire’s methodology, which I have been using for more than 20 years because I believe that applying this methodology to work with migrant women brings success, we see how much they are transforming their lives.

They invited these groups of women to work within the Warmi circles to talk about empowerment, the rights that they have as women, as human beings. And also, what rights they have in Brazil, according to the Brazilian Immigration Law.

How is the situation of migrant women in this critical moment that Brazil is living with the pandemic?

Soledad: Our group is formed by women in a situation of vulnerability, and with the pandemic, they are finding themselves in a position of extreme vulnerability. We have food emergencies, health care emergencies, the issue of work. With the pandemic, the workplaces have closed. As women are out of work, many are making masks. We already had the leaders, the women’s groups and the WhatsApp groups, so with the pandemic, it was not difficult for us to communicate and continue the work. We have not stopped until now.

First, we did a whole orientation on what is Covid-19, prevention, sanitation, we explained the importance of keeping our distance and staying at home. We did a campaign about the importance of sanitizing the houses, the sewing factories where they work because many of them have the workplace at home. We went against Bolsonaro’s government. We informed them about the emergency aid offered by the government because they also have the right to get it. We started a work that we called solidarity entrepreneurship, and with the support of some institutions, we got an initial capital so that they could start producing the masks. Through our social networks, we got help to market the masks they are producing.

Our group is formed by women in a situation of vulnerability, and with the pandemic, they are finding themselves in a position of extreme vulnerability. We have food emergencies, health care emergencies, the issue of work. With the pandemic, the workplaces have closed. As women are out of work, many are making masks.

One of the main issue women are facing during the pandemic is domestic violence. What is the situation in Brazil and what actions CEMIR is implementing to give a response to this problem?

Soledad: Domestic violence is a worrying issue at this time of isolation. We have already started an orientation campaign to denounce domestic violence, named “Quarantine yes, violence against women no”.

We are also using Arpillaria so that they can express what they are feeling during the pandemic, in this context of isolation.

Every last Sunday of the month we have a meeting to evaluate all our work. Every day we communicate with each other, but we use this meeting to talk to each other as a group. One of them, for example, revealed how afraid she is by the lack of work. She is fearful because she does not know what to do without a job. We created this project to express how immigrant women feel in this pandemic context.

I am receiving difficult stories from the women who are part of the Warmi circles. We are guiding the leaders in the neighbourhoods, and the leaders guide the women, all through the telephone.

Domestic violence is a worrying issue at this time of isolation. We have already started an orientation campaign to denounce domestic violence, named “Quarantine yes, violence against women no”.

cemir.mulherimigrante@gmail.com