What changed in the experiences of migrant domestic workers since La noir de… (Black Girl), a film directed by Ousmane Sembene, in 1966?

by Juliana da Penha

La noir de…(Black Girl) “puts Africa on the map of world Cinema”, explained Samba Gadjigo. He is the official biographer and the world’s foremost expert on the career Ousmane Sembene, father of African Cinema. This independent production, filmed in 1966 and winner of the French prize Jean Vigo, marked the birth of sub-Saharan African Cinema.

The excellence of Sembene as a storyteller, the beauty of the black and white photography, the Senegalese traditional musical instruments and other aesthetics components of the film are definitely worthy of attention. However, the legacy of colonialism and the exploitation of migrant domestic workers are the most significant aspects of this film.

Diouana Story – a story of many migrant women

The film narrates the fate of Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a young Senegalese woman desperate to find a job in Dakar. She was living a dream when a French couple living in Senegal asked her to work as a nanny for their children and promised a new life to her in France.

When she accepted to live with them in Antibe, she realised that her work would not only be caring of the children but cleaning all the time, cooking, laundry, being confined, without a day off and payment. And all the promises to visit the nice shops in France were never kept by the “Madam”.

“Now, I understand. The mistress wanted a housemaid. That’s why she picked me. Why am I here? Am I a nursery maid or a housemaid?

More than 50 years after its launch, it can be said that this film is timeless. The problems that Diouana faced then are still today. Many women still leave their country of origin, pressed by social and economic conditions, and dream of a better life abroad. But a large number of these women end up with badly paid jobs, exploitation, harassment and imprisonment. In most of the film, the voice-over reveals Diouana’s thoughts about her alienation, disappointment, loneliness and sadness.

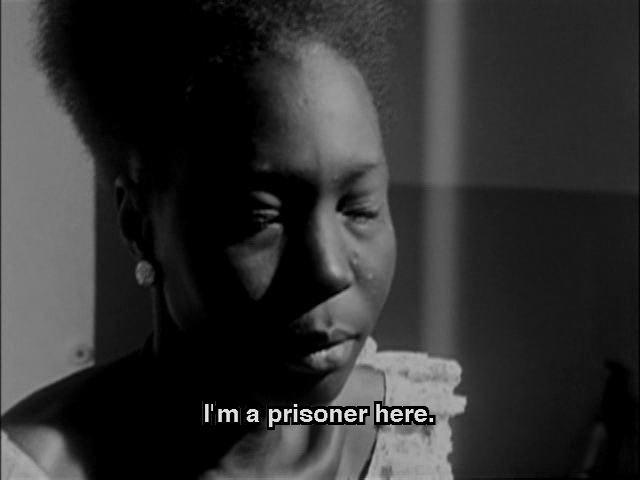

“Why am I here? I am a prisioner here”.

The numbers of migrant domestic workers

There are an estimated 11.5 million migrant domestic workers around the world, approximately 8.5 million of whom are female (Migration Data Portal). In the European Union, the vast majority of the 2.5 million domestic workers are women. One in every five domestic workers is an international migrant. A great number of migrant domestic workers are not aware of their rights. Many employers are not committed to following the labour laws, nor respect employment standards. In addition, this job is realized in private spaces and labour inspectorates are usually not allowed to enter domestic households where the work is carried out. As a result, migrant domestic workers are vulnerable to several types of abuse.

The daily life of Diouana discloses the reality of many domestic workers around the world. She never had the chance to see anything in France, only going out to buy groceries for the couple. And without any family members or friends, she spent all of her the time in the couple’s small apartment, cleaning and serving them. She soon realised that she was trapped.

“The kitchen, the bathroom, the bedroom and the living room. That’s all I do. That’s not what I came to France for!”

Postcolonial relations and exploitation of migrant domestic workers

Postcolonialism and race relations are highlighted in this classic of African Cinema. The “madam” treats Diouna like a slave. In one of the scenes, the couple invited some friends to have food in their apartment. The “madam” uses a small bell to call Diouana. While Diouana serves them, one of the men kissed her and said: “I never kissed a black woman before”. Diouna expresses her annoyance at this action and the “madam” says: “He was just playing. Your rice was really good. I am proud of you. Make us a good coffee.”

“Diouana wake up! Get up lazy bones! We are not in Africa. I didn’t hire you to sleep. The children are here! If you don’t work you don’t eat”

Women are particularly vulnerable to exploitative working conditions such as irregular work, low pay, long working hours without leave entitlements, no health and safety and work roles without dignity. Many migrant domestic workers don’t speak the local language and as a result, don’t know the laws of the host country or their rights. Domestic workers are also vulnerable to sexual violence.

Throughout the film, the deception and despair of Diouna increases. She realizes that her life in France is imprisonment and servitude.

“What are the people like here? The doors are all shut, day and night. Night and day. I came to take care of the children! Where are they? Why does the mistress always shout at me? I am no cook! I am no cleaning-woman. What am I in this house?”

The legal framework of migrant domestic work at EU level

At EU level, Article 31 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU stipulates that every worker – regardless of nationality or migration status – has the right to ‘fair and just’ working conditions that respect his or her health, safety and dignity. Article 5 of the Charter prohibits all forms of slavery, forced labour and trafficking in human beings. EU law also forbids the employment of irregularly staying third-country nationals under, particularly exploitative working conditions (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights).

It is worth noting that in 1966 there was no legal framework to protect migrant domestic workers as there is today. Today there are also support organisations and researchers that pay attention to the complex situation of these women workers, helping them to fight for their rights. But there is still a long way to go to ensure full rights for migrant domestic workers, vulnerable to the most severe forms of labour exploitation – slavery and servitude.